VON DER LUST, REGELN ZU BRECHEN YANNICK VEY IN DER KAPELLE SAINT MARIE IN ANNONAY

Yannick Vey, „Lances“, 2010

Courtesy der Künstler

Courtesy der Künstler

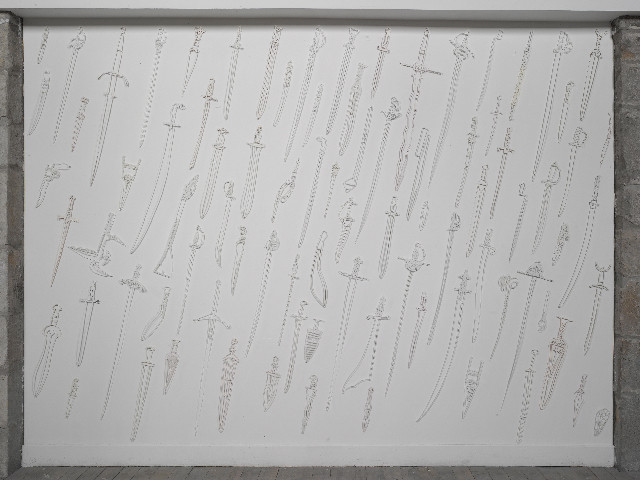

Yannick Vey, „Les épées“, 2008/9

Courtesy der Künstler

Courtesy der Künstler

Yannick Vey, „Soumission“, 2010

Courtesy der Künstler

Courtesy der Künstler

please scrol down for English version

//

VON DER LUST, REGELN ZU BRECHEN

Abstrakt-figurativ, minimal-ornamental oder solide-fragil: Solchen dichotomischen Kategorien entzieht sich das Oeuvre von Yannick Vey permanent. Er reizt die verschiedenen Grenzen der Skulptur aus und kontrastiert gezielt unterschiedliche Ansätze, Techniken und Materialien, weshalb sich sein Werk nur schlecht an einer isolierten Arbeit charakterisieren lässt. Dafür gut geeignet ist jedoch seine Ausstellung „Survivances“ in der Kapelle Saint Marie in Annonay, da sie vor Augen führt, wie sich die divergenten Arbeiten nicht nur untereinander, sondern auch mit der Architektur zu einer geschlossenen Rauminstallation fügen.

Vey interagiert als Bildhauer stets mit dem Raum. Mit vier Arbeiten füllt er die einschiffige Kapelle vollkommen aus, auch wenn er viele Freiräume lässt und somit dem aufgeladenen, ehemals sakralen Ort die Aufmerksamkeit nicht streitig macht, sondern mit ihm auf inhaltlicher, ästhetischer und räumlicher Ebene spielt. So nimmt der Besucher zuerst die Weite des (bis auf den Altar) unmöblierten Kirchenraums wahr, spürt dessen vereinzelnden, auf die eigene Existenz zurückwerfenden Effekt, bevor er sich auf das zentrale Skulpturenensemble „Lances“ (2010) konzentrieren kann.

Das Thema dieser ortsspezifischen Arbeit bildet, wie häufig in Veys Werk, die durch Waffen symbolisierte Macht, die stets den Tod einkalkuliert und damit ebenfalls das menschliche Dasein verhandelt. Die Lanzen zielen jedoch nicht auf den Betrachter, sondern auf die in barocker Manier gestaltete Altarwand: ein Machtinstrument der Kirche. Inspiriert durch die von den Religionskriegen geprägte Geschichte Annonays schmiedete Vey 35 teils mittelalterlich anmutende, teils fantastische 3 bis 6 m lange Lanzen. Doch bricht er die nahe liegende Narration von mittelalterlichen Glaubenskriegen auf, indem er die Seriennummern der als Material verwendeten Heizungsrohre auf den Lanzen belässt, womit der Konflikt in der Gegenwart verortet wird. Diese Verwendung von Alltagsmaterialien bildet eine Konstante in Veys Werk, das nicht nur in der Materialwahl, sondern auch in seiner Ästhetik der Arte Povera verwandt ist. So dienen den Lanzen unbehauene Steinbrocken aus der Gegend um Annonay als Sockel, der bei Vey in Brâncușis’scher Tradition stets aus einem anderen Material besteht als die eigentliche Plastik.

Weniger archaisch, denn ornamental verziert und regelmäßig arrangiert sind die Stichwaffen in der Wandarbeit „Les épées“ (2008/9), die in ihrer ephemeren Erscheinung der starken räumlichen Präsenz von „Lances“ diametral entgegensteht. In einer schmalen Nische gegenüber der Fensterfront werden die Decoupagen von den Schatten der Lanzen überlagert und fallen erst auf den zweiten Blick auf, zumal der Putz an mehreren Stellen ein Muster an Löchern aufweist und überdies die farbige Scheinarchitektur an Fensterbögen und Decke um den Blick konkurriert. Wie bei diesen Trompe-l’œils im Stil Luis XIV changieren auch Veys Decoupagen, die er per Skalpell aus dem Papier seziert, zwischen der zweiten und dritten Dimension. Die fragilen Arbeiten sind gleich einem Relief als Halbplastik zu verstehen, da sie mit Abstand gehängt sind, so dass auch ihre eigenen Schatten oder die sublimen farbigen Reflexionen des bei „Les épées“ umseitig kolorierten Papiers zur Arbeit gehören.

In seinen Decoupagen schichtet Vey häufig zwei Motive übereinander und kreiert so Vexierbilder. Welchen Vorbildern er dabei folgt, wird in „Survivances“ (2010) erkennbar: Zehn Hände, die per Fingeralphabet das Wort Survivance formen, werden mit Ikonen aus der (meist christlichen) Kunstgeschichte bzw. einem Selbstzitat überlagert. Allen gemein ist eine, für Veys Oeuvre charakteristische, sexuelle Anspielung – mal ostentativ, wie in der frühen Darstellung eines Mannes mit Erektion in der Grotte von Lasceaux, mal als Vexierbild versteckt, wie bei Guido Renis „St. Sebastian“. Mit diesen Zitaten verweist Vey auf Strategien, mit denen Künstler seit langem die Zensur unterminieren und in deren Tradition er agiert.

Als (sicher nicht unironische) Anspielung auf die strafende Hand Gottes kann „Soumission“ (2010) gelesen werden. Eine Hand liegt hier jeweils dreizehn Köpfen auf, genauer aus ungebranntem Ton modellierten Selbstportraits, die ihrerseits auf einem Holzsockel in Form einer Werkbank aufgereiht sind. Diese erinnert angesichts der zu Messerschmidt-haften Grimassen verzogenen Mimik an eine Folterbank oder einen Opfertisch und Ähnlichkeiten zu Bruce Naumans „Heads“ unterstützen das verstörende Moment der Arbeit. Vey scheint hier die Strafe für seine Regelbrüche zu antizipieren, die er bereits lustvoll begangen hat und weiter begehen wird – mal über poetische Transformationen, mal in brutaler Drastik, immer gemäß des Yin-Yang-Prinzips.

//

ON THE DELIGHT OF BREAKING THE RULES

Abstract–figurative, minimal–ornamental or solid–fragile: the works of Yannick Vey elude such dichotomic categories. The artist experiments with the different limits of sculpture and purposely contrasts various approaches, techniques and materials. That’s why his oeuvre cannot easily be characterized through an isolated piece of work. But his exhibition "Survivances" in the Chapel of Sainte Marie in Annonay is very suitable to understand his creation as it shows quite plainly not only how the diverging works fit together but also how they interact with the architecture resulting in a cohesive space installation.

As a sculptor Vey always interacts with space. With four works he completely occupies the chapel though he leaves a lot of free space. Thus he does not take the attention off the spiritually charged place, but plays with it on the levels of content, aesthetics and space. Upon entering, one first perceives the width of the chapel’s space, before concentrating on the central sculptural ensemble "Lances" (2010).

The theme of this site-specific work is – like often in Vey’s oeuvre – power as symbolized by weapons that always reckons with death and thus bargains with human existence. However, the lances are not aimed at the spectator, but at the wall of the altar designed in Baroque style: an instrument of the power of the Church. Inspired by the history of Annonay, which is marked by the Wars of Religion, Vey forged 35 lances of 3 to 6 m length, partly with a medieval appearance, partly fantastic. But he breaks up the suggestive narration of the medieval wars by leaving the serial numbers of the heating pipes he used as material for the lances thus locating the conflict in the present. This use of everyday materials is a constant in Vey’s works which are related to Arte Povera not only through the choice of materials, but also through their aesthetics. Hence, unhewn rocks from the area around Annonay serve as pedestals for the lances – in the tradition of Constantin Brâncuşi, with Vey the pedestal is always of another material than the sculpture itself.

On the contrary, the weapons of the work "Les épées" (2008/9) are less archaic but rather ornamentally decorated and orderly arranged. Their ephemeral appearance contrasts diametrically with the strong spatial presence of "Lances". In a small niche the decoupages are superimposed by the shadows of the lances and only catch one’s eyes at second sight, especially as the plaster features a pattern of holes at several spots and the illusory architecture of the window arches and the ceiling also competes for the visitors‘ gaze. Like these trompe-l’œils in the style of Louis XIV, Vey’s decoupages change between the second and the third dimension. These fragile works are to be understood as half sculptures similar to reliefs. They are hung with a distance to the wall so that their own shadows and the sublime colourful reflections (resulting from the coloured backsides) form a part of the work.

In his decoupages Vey often layers two motives one upon the other and thus creates picture puzzles. In "Survivances" (2010) the models he follows become identifiable: ten hands forming the word "Survivance" in finger spelling are overlaid by icons of (mostly Christian) art history or by a self-reference. Common to all of them is a sexual allusion, characteristic of Vey’s oeuvre – sometimes ostentatious like the early depiction of a man with an erection in the grotto of Lascaux, sometimes hidden in a picture puzzle like in Guido Reni’s "San Sebastian". With these references Vey points out strategies with which artists have been undermining censorship for centuries, and places himself in their tradition.

"Soumission" (2010) can be read as an allusion (surely not without irony) to the punishing hand of God. A hand rests on each one of thirteen heads, more specifically self-portrayals modeled of unburnt clay, themselves aligned on a wooden pedestal. Given the Franz Xaver Messerschmidt-like grimaces of their mimics it reminds one of a torture rack or a sacrificial altar. Similarities with Bruce Nauman’s "Heads" further underline the disturbing aspects of this work. Vey seems here to anticipate punishment for breaking the rules, a delict he has already committed with great delight and will continue to commit – sometimes through poetical transformations, sometimes in drastic ways, always according to the principle of yin and yang.

//

Translation by Ulrich Fügener and Sara Rowe

//

veröffentlicht in Französisch und Englisch unter in Semaine: http://www.analogues.fr/semsupvey.html

//