REVIEW ON DRAFT DECEIT AT KUNSTNERNES HUS, OSLO

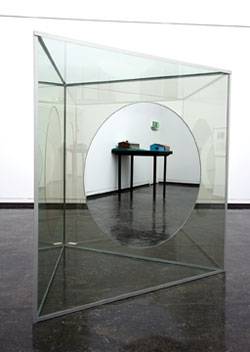

In one of the two spacious Modernist halls upstairs Dan Graham and Carol Bove’s works dominated, creating a cross-generational dialogue. In his 1978 architectural model of a comfortable suburban house with a transparent front, Alteration to a Suburban House, Graham uses glass and mirrors both to unveil architectural structures and to suggest psychological states. In her sculptural assemblages, meanwhile, Bove holds a mirror to the era when Graham first began creating his works, arranging materials such as photographs, vases, books and other paraphernalia from the late 1960s and early ’70s on shelves (Das Energei, The Energy, 2005–6). Both artists also find ways to prescribe our point of view through abstract spatial relationships. Nearly five metres tall, consisting of hundreds of thin strips of bronze suspended from the ceiling, Bove’s The Night Sky over Oslo, March 16, 2006, at 9pm (2005–6) must be viewed from underneath, as if the strips were stars in the sky. A few metres away, Graham’s small pavilion Triangle with Circular Inserts – Variation B (1991) has to be entered through a ‘rabbit hole’ in the glass. Such effective pairings thickened the exhibition’s plot and suggested a possible narrative of similar dialogues throughout the entire show.

Such expectations were thwarted, however, in the second of the upstairs halls, where the sounds from Matthew Buckingham’s film Situation Leading to a Story (1999) and Torbjørn Rødland’s video Blues for Bigfoot (2005) drowned each other out, irredeemably obscuring the content of both works. Seminal works meant to enter into dialogue with younger works included ten typed letters with photographs by John Baldessari, Ingres and Other Parables (1971), with notes on the art world and its menace, as well as one of Jeff Wall’s light-boxes Boys Cutting Through a Hedge (2003) and the by now multi-reproduced Ozewald (1989), by Cady Noland, portraying Lee Harvey Oswald’s murder. The cross-readings and multilayered intricacies that were tangible between Bove and Graham’s work became impossible here, not only because of the poor acoustics but also because of the scanty amount of work and the vast space between works. I was left disappointed, and not even an alteration of the architecture of the Kunstnernes Hus by Corey McCorkle, Heiligenschein (Halo, 2005), could make up for it. McCorkle inserted a circle inside the plaster wall behind the central rose window in the façade of the building, creating a kind of divine light within the white cube.

On the ground floor Sam Durant’s text piece Like, Man, I’m Tired of Waiting (2001) wryly replied to Weiner’s text piece upstairs. But Kerry Tribe’s double-projection film Here & Elsewhere (2002) was the showstopper. With the experimental and documentary television series by Jean-Luc Godard about two children in France in the 1970s in mind, Tribe explores and perhaps even exploits an adolescent girl’s answers to advanced philosophical questions. The film proposes questions not only about authenticity and the unique, but also about how an audience can be seduced by a narrative and the differing ways we regard the exploitation of people through the medium of television from three decades earlier.

It is not clear what ‘Draft Deceit’ is communicating or how the artists were selected – there are plenty who could have fitted in with the show’s theme equally neatly – or why the spaces were treated with such reverence. Trad-itionally (and beautifully) installed art works originally meant to dismantle architectural structures within a traditional institutional space turn into dead icons of the past. Juxtaposing works in closer proximity would have made the intended cross-readings more fruitful. Expectations should be kept at a safe low, but in this case the synergy between Bove and Graham, and Tribe’s film, made up for some of the exhibition’s missed opportunities.

Power Ekroth