Juan Pérez Agirregoikoa | Inner Beauty

12 Jun - 25 Jul 2010

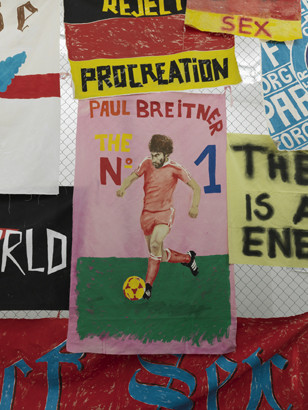

Refuse work! Hate your bodies! Forget your parents! Curtly formulated maxims of revolution. But which one? And for what? For his second solo exhibition at Clages Gallery, Juan Pérez Agirregoikoa sketches a sarcastic study of the notion of revolution. Hanging on a barricade fence are watercolors that, based on political banners, articulate catchphrases of the opposition.

Forming the central focus of the installation is a likeness of German football star and 1974 World Champion Paul Breitner, idealized as Number 1. Breitner’s political views were heavily discussed in his day: one famous photograph shows him seated in a rocking chair in intellectual style, reading a Chinese Communist propaganda newspaper, a dog at his feet. Breitner claimed to have read Marx and Lenin, referred to himself as a Maoist and was derided in the West German press for his luxurious lifestyle. In 1974 he switched to the Spanish football team Real Madrid, of all things fanatic dictator Franco’s favorite team.

It is due to these inconsistencies that not he but his rather unpolitical colleague Günther Netzer became the 68ers’ football idol. At the same time his connections to the Western Left was obvious. The Chinese Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) generated waves of enthusiasm. Early radicals named anti-authoritarian Mao Zedong a role model for student mobilization. Countless so-called “k-groups” formed after the student movement; citing Marxist-Leninist theory or Maoism as an example, they pushed for revolution in Western Europe as well. The fact that the so-called peaceful revolution entailed countless murders went unmentioned, as was Mao’s self-staged personality cult.

Revolution in the original sense of the word refers to a return, a reversal, the renewal of an old, legitimate condition. From the swing-back emerged a vernacular, radical, often violent social transformation of the existing political or social relations. Agirregoikoa argues along the lines of both definitions, conceives of revolution as postulated by Jacque Lacan, who told his students in 1969 that in their revolutionary ambitions they were looking for and will receive a new master. This cycle is a subject that runs through Agirregoika’s work and finds expression in the common linguistic phrases of resistence.

Friederike Gratz

Forming the central focus of the installation is a likeness of German football star and 1974 World Champion Paul Breitner, idealized as Number 1. Breitner’s political views were heavily discussed in his day: one famous photograph shows him seated in a rocking chair in intellectual style, reading a Chinese Communist propaganda newspaper, a dog at his feet. Breitner claimed to have read Marx and Lenin, referred to himself as a Maoist and was derided in the West German press for his luxurious lifestyle. In 1974 he switched to the Spanish football team Real Madrid, of all things fanatic dictator Franco’s favorite team.

It is due to these inconsistencies that not he but his rather unpolitical colleague Günther Netzer became the 68ers’ football idol. At the same time his connections to the Western Left was obvious. The Chinese Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) generated waves of enthusiasm. Early radicals named anti-authoritarian Mao Zedong a role model for student mobilization. Countless so-called “k-groups” formed after the student movement; citing Marxist-Leninist theory or Maoism as an example, they pushed for revolution in Western Europe as well. The fact that the so-called peaceful revolution entailed countless murders went unmentioned, as was Mao’s self-staged personality cult.

Revolution in the original sense of the word refers to a return, a reversal, the renewal of an old, legitimate condition. From the swing-back emerged a vernacular, radical, often violent social transformation of the existing political or social relations. Agirregoikoa argues along the lines of both definitions, conceives of revolution as postulated by Jacque Lacan, who told his students in 1969 that in their revolutionary ambitions they were looking for and will receive a new master. This cycle is a subject that runs through Agirregoika’s work and finds expression in the common linguistic phrases of resistence.

Friederike Gratz