Georg Baselitz

The Heroes

14 Jul - 22 Oct 2017

Georg Baselitz, Rebel (Rebell), 1965, Oil on canvas, 162 x 130 cm, Tate: Purchased 1982, London

© Georg Baselitz, 2017, Photo: Friedrich Rosenstiel, Cologne

© Georg Baselitz, 2017, Photo: Friedrich Rosenstiel, Cologne

Georg Baselitz, Blocked Painter (Versperrter Maler), 1965, Oil on canvas, 162 x 130 cm, MKM Museum Küppersmühle für Moderne Kunst, Duisburg, Collection Ströher

© Georg Baselitz, 2017, Photo: Archiv Sammlung Ströher

© Georg Baselitz, 2017, Photo: Archiv Sammlung Ströher

Georg Baselitz, Bonjour Monsieur Courbet, 1965, Oil on canvas, 162 x 130 cm Collection Thaddaeus Ropac, Paris – Salzburg

© Georg Baselitz, 2017, Photo: Frank Oleski, Cologne

© Georg Baselitz, 2017, Photo: Frank Oleski, Cologne

Georg Baselitz, Curly-One (Lockiger), 1966, Oil on canvas, 162 x 114 cm, Privately owned

© Georg Baselitz 2017, Photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin

© Georg Baselitz 2017, Photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin

Georg Baselitz, Adler 53 - Held 65 (Remix), 2007, Oil on canvas, 300 x 250 cm Privately owned

© Georg Baselitz, 2017, Photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin

© Georg Baselitz, 2017, Photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin

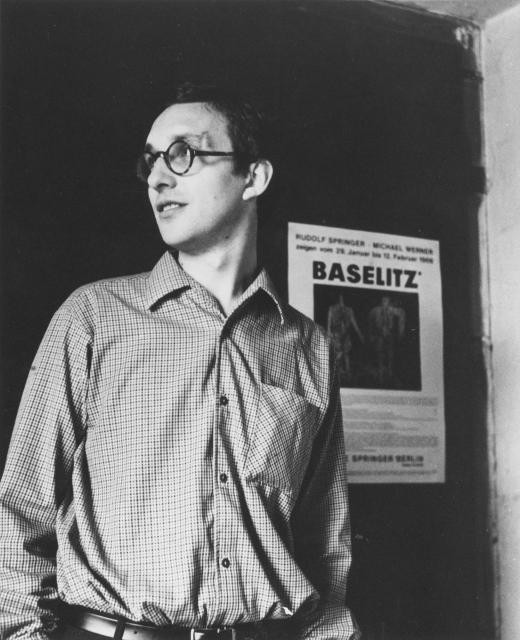

GEORG BASELITZ

The Heroes

14 July - 22 October 2017

What I could never escape was Germany, and being German

Georg Baselitz

In 1965/66, Georg Baselitz executed approximately 60 paintings and 130 drawings which have entered art history under the collective term of Hero Paintings or New Types. These paintings of dramatically distorted and powerful figures reveal a remarkable tension between aggression and melancholy, between grand gesture and trepidation. The lone male figures appear as wounded and vulnerable characters in torn uniforms. They stand in implied battered landscapes, surrounded by recurring utensils, including painters’ accessories and instruments of torture. In these depictions, Baselitz explored his own individual position and evolution as a painter. In doing so, he linked personal experiences with artistic and literary impressions.

With these desolate, melancholic Types or Heroes, the then 27-year-old artist consciously defied any clear form of artistic and political categorization, refusing to be appropriated by existing systems. During the Cold War era, he balked at any attribution to ideologically, dogmatically connoted styles, such as “international” abstraction or “socialist” realism. With his fundamentally skeptical attitude, he emphasized the ambivalent aspects of his own age and the past, which was yet to be processed The artist depicted a supposed reality, an attitude born of an inner necessity, in a way that was frowned upon in the context of the success story of Germany’s economic miracle.

In the recent Remix Paintings, Baselitz has revisited the most provocative aspects of his own history, such as Die grosse Nacht in Eimer and Die grossen Freunde, and made new versions or interpretations of them with the experience and the benefit of hindsight. Enlarged and rapidly painted with swathes of bright, transparent hues across the white canvas and explosive, meandering lines, the RemixPaintings are radical transubstantiations—part caricature, part ghost—of their muted, more ponderous predecessors. The spontaneity with which they are executed gives rise to mnemonic flashes of things past, present, and future. The impulse to improve, clarify, and update is clearly evident, but the haunting, fleeting quality of the Remix works also has to do with a mature artist’s meditations on time, presence, failure, and possibility.

Even today, the perception remains that Georg Baselitz has found an eternal formal language for his struggle to express an attitude and self-assertion in an era marked by instability.

An exhibition of the Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main, in collaboration with the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao.

Rebel (Rebell), 1965

REBEL, 1965

Both as an artist and an individual, Georg Baselitz was very aware of life in the highly charged environment of the Cold War. At the same time, in 1965, when he was 27, he was also trying to establish his own position between abstraction and figuration.

“I was certainly an angry artist, that’s how it was – an angry young man, and wasn't happy with anything going on around me – nothing at all. And I had a strong desire for peace and harmony since, of course, I also had a wife and two children. This need for harmony was constantly being disturbed – both by myself and my surroundings – so I tried to develop an internal world. A world where I could say that’s the usual world of art. And if you bear in mind that artists then were far more on their own, far more isolated, than today, and much less in the public eye than now – since there was absolutely no art market, there were no auctions, and only very limited exhibitions – well, it was really a tough time for artists – then you can understand better how it all happened.

But actually, my idea was always to do something which was against things – without now being able to formulate that anti-attitude any better – I was just simply anti whatever it was. Normally, that’s a pre-puberty or adolescent reaction which is no longer right for a 25-year-old artist – you should be 15 or at most 18. But I have to say, in my case this adolescent state continued a very, very long time. Yet these paintings certainly have retained their element of surprise – even for me, and for all that time, all these decades. That’s why I find it so interesting and think they definitely ought to be exhibited. Not as a historical event, but as a biographical event – since I’ve moved on, and I’m doing quite different things today. And there’s sure to be any number of people who know me, but who would never connect me with this sort of picture ... because they know me as the ‘upside down’ artist, or someone who paints birds ... or what the hell do I know... So even today, there are still totally unanswered questions about many, many aspects of these paintings.”

BLOCKED PAINTER (VERSPERRTER MALER), 1965

The majority of figures in this series are wearing uniforms. A person in uniform may be surrendering their own individuality, yet at the same time they demonstrate membership of an organisation or association, and outwardly display their status. Yet in this series of works, such meanings soon dissolve in the face of these uniforms, tattered and torn – their individual ragged states also subverting the ideal of equality and a protective community. Baselitz’s uniforms, though, are not sheer fantasy, but based on real models.

"In the period that followed, there was a fashion – perhaps an obsessive fashion – to wear army uniforms, and not only in Germany, but also in France – since we bought the uniforms in Germany... I mean, in France. It was the ‘military look’ and at the Paris flea market – quite seriously – you could find a vast arsenal of used uniforms. And all the women – my wife as well – and the guys – we all went shopping there, bought this stuff and wore it. So if you wanted to be en vogue in Berlin, you wore army clothing, predominantly American, and from the Korean war or Vietnam war. But I didn’t know all that at the time I was painting these works. They say that artists always have something visionary – and I sensed that something like that was going to happen. In reality, if you take the books literally which I just mentioned, naturally it was people who were in the White Russian army, in the Soviet Red Army, and then the so-called ‘green army’, the forest army of partisans, and so on. And if they didn’t wear armbands – at the very least armbands – , they wore some kind of uniform. It wasn’t a fantasy uniform like D’Annunzio, but one that could be found hundreds, thousands of times – depending on how large the body of troops was. And the uniform colour is what is called field grey or mouse grey, or a kind of earth ochre, and the works always move between these colours. What’s noticeable with all the figures I painted is that they hardly look at all – let’s say – as if they are properly wearing a uniform. Instead, the uniforms are ragged, the clothing is torn, the trousers are torn, with the trousers often falling down and so on – so it depicts a fairly wretched state.

And that wretched state is visible across the entire picture. So all the props in the image show signs of destruction – the trees are kaput, the houses are kaput, the fields are kaput, the objects are kaput. Nothing can actually be fully utilised.And that wretched state is visible across the entire picture. So all the props in the image show signs of destruction – the trees are kaput, the houses are kaput, the fields are kaput, the objects are kaput. Nothing can actually be fully utilised.“

BONJOUR MONSIEUR COURBET, 1965

Baselitz frequently included the painter among his heroes, although this character might seem unrelated to the rest. In this case the theme is confirmed by the title, which mentions the 19th-century French realist painter Gustave Courbet.

These works allowed Baselitz to reflect on his own personal condition, on his role and his contribution to painting.

If I had been born someone else, born somewhere else, I would have certainly been able to produce more felicitous pictures.

But this awareness of himself as a painter affected not only his choice of themes but also how he rendered them. In his own words:

I'm a German artist: what I do is rooted in the German tradition. It's ugly and expressive.

The connection between his heroes and Expressionism is obvious. His characters do not have harmonious, idealized proportions, their disproportion is a deliberate attempt to provoke emotional responses. But those same emotions are suggested in the energetic, pastose brushstrokes, possessing an independent momentum.

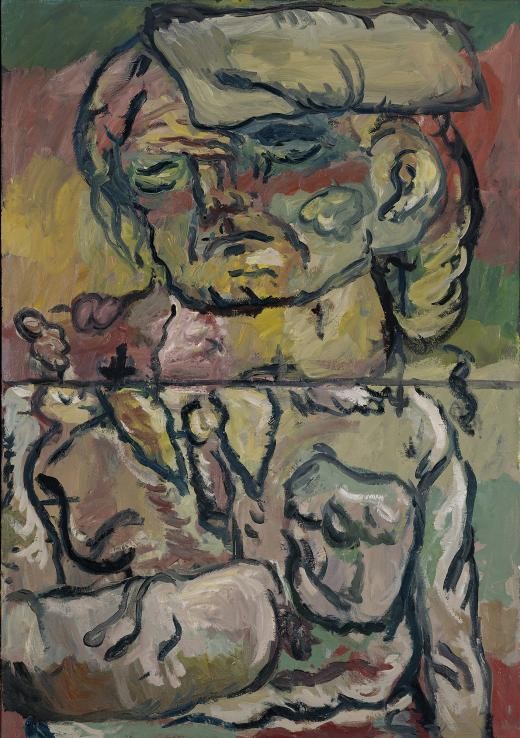

Curly-One (Lockiger), 1966

THE FRACTURES PAINTINGS

Starting in 1966, Georg Baselitz developed the so-called “Fracture Paintings”, which continued the heroes theme. Now he divided the canvas into two or three horizontal sections and painted the body fragments independently of one another. They are interrelated – but somehow don’t really join to form a cohesive figure.

“I have tried to readjust or tidy up something I created unconsciously, passionately, and purely emotionally. And that is something that I am still trying to do today. I think most orderly people are those who keep accounts books. They add upt by drawing a line and draw those numbers then top them up and then have the sum total at the bottom. I think being orderly is a wonderful thing and I have tried to transfer that to my pictures. Now, I thought, you have a large canvas if that is what you want and can start at the top or base if that is what you want. And it is usually at the top then you stop and start again a new. You have got upper part section in your memory but you don’t know exactly where you stopped so you know where you have to start again, so you postponed it. All intentionally”

REMIX

Remix is the title of a series of paintings that Georg Baselitz began in 2005, in which he revisited earlier works. Establishing an ideal continuity between past and present, the exhibition includes a selection of these paintings from the Remix cycle which heralded the Heroes and New Types of 2007 and 2008.

In his Remix paintings, Baselitz revisited the most provocative aspects of his own history, such as Die grosse Nacht im Eimer and Die grossen Freunde, and made new versions or interpretations of them with the benefit of hindsight. Enlarged and rapidly painted with swathes of bright, transparent hues and explosive, meandering lines, the Remix paintings are radical transubstantiations—part-caricature, part-ghost—of their more ponderous predecessors. The spontaneity with which they are executed gives rise to mnemonic flashes of things in the past, present, and future.The impulse to clarify and update is evident, but the haunting, fleeting quality of this work also has to do with a mature artist's meditations on time, presence, failure, and possibility. The artist has explained...

"I like the word 'remix' because it comes from youth culture."

For all their similarities, there are several important differences between this group of paintings and the earlier series. The most obvious is the choice of palette. Instead of the earthy tones that dominate the Heroes series, these works are painted in cool, vibrant colors. The artist also plays more with the white of the canvas to suggest a negation of space, situating the characters outside of the narrative. And in contrast to the solid bulks of his original heroes, these figures are rendered with more agile, energetic brushstrokes that convey a sense of dynamic movement. The artist explained what he sought to achieve with this "Remix":

“If you're remixing popular music you change the rhythm or the sound... What I do is something entirely different. I have thought for a long time about what to call what I do. I like the word "remix" because it comes from youth culture.”

The Heroes

14 July - 22 October 2017

What I could never escape was Germany, and being German

Georg Baselitz

In 1965/66, Georg Baselitz executed approximately 60 paintings and 130 drawings which have entered art history under the collective term of Hero Paintings or New Types. These paintings of dramatically distorted and powerful figures reveal a remarkable tension between aggression and melancholy, between grand gesture and trepidation. The lone male figures appear as wounded and vulnerable characters in torn uniforms. They stand in implied battered landscapes, surrounded by recurring utensils, including painters’ accessories and instruments of torture. In these depictions, Baselitz explored his own individual position and evolution as a painter. In doing so, he linked personal experiences with artistic and literary impressions.

With these desolate, melancholic Types or Heroes, the then 27-year-old artist consciously defied any clear form of artistic and political categorization, refusing to be appropriated by existing systems. During the Cold War era, he balked at any attribution to ideologically, dogmatically connoted styles, such as “international” abstraction or “socialist” realism. With his fundamentally skeptical attitude, he emphasized the ambivalent aspects of his own age and the past, which was yet to be processed The artist depicted a supposed reality, an attitude born of an inner necessity, in a way that was frowned upon in the context of the success story of Germany’s economic miracle.

In the recent Remix Paintings, Baselitz has revisited the most provocative aspects of his own history, such as Die grosse Nacht in Eimer and Die grossen Freunde, and made new versions or interpretations of them with the experience and the benefit of hindsight. Enlarged and rapidly painted with swathes of bright, transparent hues across the white canvas and explosive, meandering lines, the RemixPaintings are radical transubstantiations—part caricature, part ghost—of their muted, more ponderous predecessors. The spontaneity with which they are executed gives rise to mnemonic flashes of things past, present, and future. The impulse to improve, clarify, and update is clearly evident, but the haunting, fleeting quality of the Remix works also has to do with a mature artist’s meditations on time, presence, failure, and possibility.

Even today, the perception remains that Georg Baselitz has found an eternal formal language for his struggle to express an attitude and self-assertion in an era marked by instability.

An exhibition of the Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main, in collaboration with the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao.

Rebel (Rebell), 1965

REBEL, 1965

Both as an artist and an individual, Georg Baselitz was very aware of life in the highly charged environment of the Cold War. At the same time, in 1965, when he was 27, he was also trying to establish his own position between abstraction and figuration.

“I was certainly an angry artist, that’s how it was – an angry young man, and wasn't happy with anything going on around me – nothing at all. And I had a strong desire for peace and harmony since, of course, I also had a wife and two children. This need for harmony was constantly being disturbed – both by myself and my surroundings – so I tried to develop an internal world. A world where I could say that’s the usual world of art. And if you bear in mind that artists then were far more on their own, far more isolated, than today, and much less in the public eye than now – since there was absolutely no art market, there were no auctions, and only very limited exhibitions – well, it was really a tough time for artists – then you can understand better how it all happened.

But actually, my idea was always to do something which was against things – without now being able to formulate that anti-attitude any better – I was just simply anti whatever it was. Normally, that’s a pre-puberty or adolescent reaction which is no longer right for a 25-year-old artist – you should be 15 or at most 18. But I have to say, in my case this adolescent state continued a very, very long time. Yet these paintings certainly have retained their element of surprise – even for me, and for all that time, all these decades. That’s why I find it so interesting and think they definitely ought to be exhibited. Not as a historical event, but as a biographical event – since I’ve moved on, and I’m doing quite different things today. And there’s sure to be any number of people who know me, but who would never connect me with this sort of picture ... because they know me as the ‘upside down’ artist, or someone who paints birds ... or what the hell do I know... So even today, there are still totally unanswered questions about many, many aspects of these paintings.”

BLOCKED PAINTER (VERSPERRTER MALER), 1965

The majority of figures in this series are wearing uniforms. A person in uniform may be surrendering their own individuality, yet at the same time they demonstrate membership of an organisation or association, and outwardly display their status. Yet in this series of works, such meanings soon dissolve in the face of these uniforms, tattered and torn – their individual ragged states also subverting the ideal of equality and a protective community. Baselitz’s uniforms, though, are not sheer fantasy, but based on real models.

"In the period that followed, there was a fashion – perhaps an obsessive fashion – to wear army uniforms, and not only in Germany, but also in France – since we bought the uniforms in Germany... I mean, in France. It was the ‘military look’ and at the Paris flea market – quite seriously – you could find a vast arsenal of used uniforms. And all the women – my wife as well – and the guys – we all went shopping there, bought this stuff and wore it. So if you wanted to be en vogue in Berlin, you wore army clothing, predominantly American, and from the Korean war or Vietnam war. But I didn’t know all that at the time I was painting these works. They say that artists always have something visionary – and I sensed that something like that was going to happen. In reality, if you take the books literally which I just mentioned, naturally it was people who were in the White Russian army, in the Soviet Red Army, and then the so-called ‘green army’, the forest army of partisans, and so on. And if they didn’t wear armbands – at the very least armbands – , they wore some kind of uniform. It wasn’t a fantasy uniform like D’Annunzio, but one that could be found hundreds, thousands of times – depending on how large the body of troops was. And the uniform colour is what is called field grey or mouse grey, or a kind of earth ochre, and the works always move between these colours. What’s noticeable with all the figures I painted is that they hardly look at all – let’s say – as if they are properly wearing a uniform. Instead, the uniforms are ragged, the clothing is torn, the trousers are torn, with the trousers often falling down and so on – so it depicts a fairly wretched state.

And that wretched state is visible across the entire picture. So all the props in the image show signs of destruction – the trees are kaput, the houses are kaput, the fields are kaput, the objects are kaput. Nothing can actually be fully utilised.And that wretched state is visible across the entire picture. So all the props in the image show signs of destruction – the trees are kaput, the houses are kaput, the fields are kaput, the objects are kaput. Nothing can actually be fully utilised.“

BONJOUR MONSIEUR COURBET, 1965

Baselitz frequently included the painter among his heroes, although this character might seem unrelated to the rest. In this case the theme is confirmed by the title, which mentions the 19th-century French realist painter Gustave Courbet.

These works allowed Baselitz to reflect on his own personal condition, on his role and his contribution to painting.

If I had been born someone else, born somewhere else, I would have certainly been able to produce more felicitous pictures.

But this awareness of himself as a painter affected not only his choice of themes but also how he rendered them. In his own words:

I'm a German artist: what I do is rooted in the German tradition. It's ugly and expressive.

The connection between his heroes and Expressionism is obvious. His characters do not have harmonious, idealized proportions, their disproportion is a deliberate attempt to provoke emotional responses. But those same emotions are suggested in the energetic, pastose brushstrokes, possessing an independent momentum.

Curly-One (Lockiger), 1966

THE FRACTURES PAINTINGS

Starting in 1966, Georg Baselitz developed the so-called “Fracture Paintings”, which continued the heroes theme. Now he divided the canvas into two or three horizontal sections and painted the body fragments independently of one another. They are interrelated – but somehow don’t really join to form a cohesive figure.

“I have tried to readjust or tidy up something I created unconsciously, passionately, and purely emotionally. And that is something that I am still trying to do today. I think most orderly people are those who keep accounts books. They add upt by drawing a line and draw those numbers then top them up and then have the sum total at the bottom. I think being orderly is a wonderful thing and I have tried to transfer that to my pictures. Now, I thought, you have a large canvas if that is what you want and can start at the top or base if that is what you want. And it is usually at the top then you stop and start again a new. You have got upper part section in your memory but you don’t know exactly where you stopped so you know where you have to start again, so you postponed it. All intentionally”

REMIX

Remix is the title of a series of paintings that Georg Baselitz began in 2005, in which he revisited earlier works. Establishing an ideal continuity between past and present, the exhibition includes a selection of these paintings from the Remix cycle which heralded the Heroes and New Types of 2007 and 2008.

In his Remix paintings, Baselitz revisited the most provocative aspects of his own history, such as Die grosse Nacht im Eimer and Die grossen Freunde, and made new versions or interpretations of them with the benefit of hindsight. Enlarged and rapidly painted with swathes of bright, transparent hues and explosive, meandering lines, the Remix paintings are radical transubstantiations—part-caricature, part-ghost—of their more ponderous predecessors. The spontaneity with which they are executed gives rise to mnemonic flashes of things in the past, present, and future.The impulse to clarify and update is evident, but the haunting, fleeting quality of this work also has to do with a mature artist's meditations on time, presence, failure, and possibility. The artist has explained...

"I like the word 'remix' because it comes from youth culture."

For all their similarities, there are several important differences between this group of paintings and the earlier series. The most obvious is the choice of palette. Instead of the earthy tones that dominate the Heroes series, these works are painted in cool, vibrant colors. The artist also plays more with the white of the canvas to suggest a negation of space, situating the characters outside of the narrative. And in contrast to the solid bulks of his original heroes, these figures are rendered with more agile, energetic brushstrokes that convey a sense of dynamic movement. The artist explained what he sought to achieve with this "Remix":

“If you're remixing popular music you change the rhythm or the sound... What I do is something entirely different. I have thought for a long time about what to call what I do. I like the word "remix" because it comes from youth culture.”