KLEINE BILDER | MARTIN GERMANN 2022

1)

If there are any artists from the Berlin of the late 1990s who have stayed true to their stances—then—well, on the face of it there are actually many of them. “Staying true to oneself” is a pliable phrase, adapting to infinitely many versions of life. And yet Klaus Jörres is by a long shot the first one whom it brings to my mind. Maybe because, but not only because, he was one of the first artists I had the opportunity to get to know in person in Berlin. Jörres, whose new works will be my subject in the following pages, moved to Berlin in 1999, shortly after completing his studies in painting in Maastricht. And despite this training, the painterly gesture and the associated heroism of individual expression would always remain alien to him.

He was drawn instead to an exploration of the uncharted media landscapes that opened up in the 1990s with the rapid growth of the WWW and the promises of participation and democracy bound up with it, embedded in all sorts of social and political utopias—dazzling prospects, whose visual potency was inversely proportional to the processor speeds of the time. Looking back now, it’s hard to avoid the impression that it was primarily the latter that rose in the 2000s and 2010s. An engineering mindset focused on feasibility was capable of translating the networking fantasies of the 1990s into reality, but by the same token it recoded them so thoroughly that we’re now left with five highest-grossing corporate behemoths that keep on growing and expanding their monopoly power. But perhaps that’s a different story.

Having arrived in Berlin in 1999, Jörres promptly enrolled at the Berlin University of the Arts, deep in the city’s West, to study with Katharina Sieverding. The program broadened his perspective on technical images, with their production, distribution, and circulation, and, no less importantly, the social component, including the mechanisms of inclusion and exclusion that are characteristic of group dynamics. These aspects were salient not only in Sieverding’s work and teaching—like Jörres, she grew up in the Rhine-Ruhr-area—but also in the club culture that had sprung up in the architectural legacy of socialist East Germany: a practice of emancipation that thrived on the interface (sic) between industrial production and social utopia, that made itself at home in the proverbial heart of the machine by affirming it. For it’s worth noting that the platform-capitalist labor regimes of today were already taking shape in the slipstream of those halcyon days, their emergence fueled by the dogma of boundless creativity that has since metastasized throughout the city.

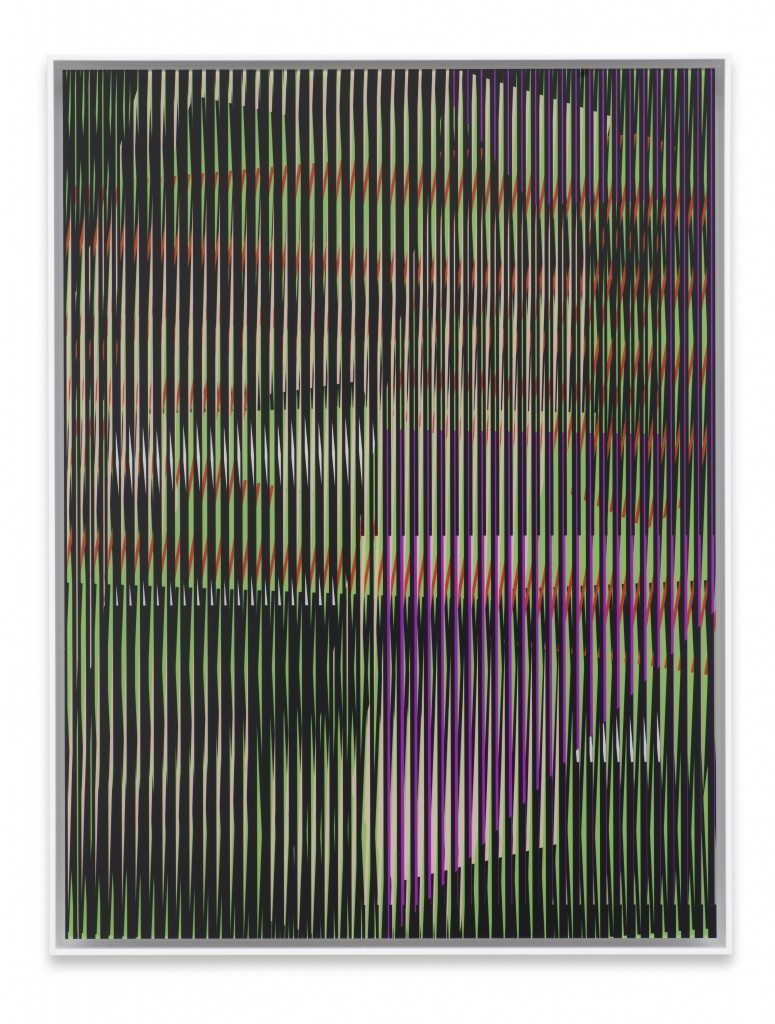

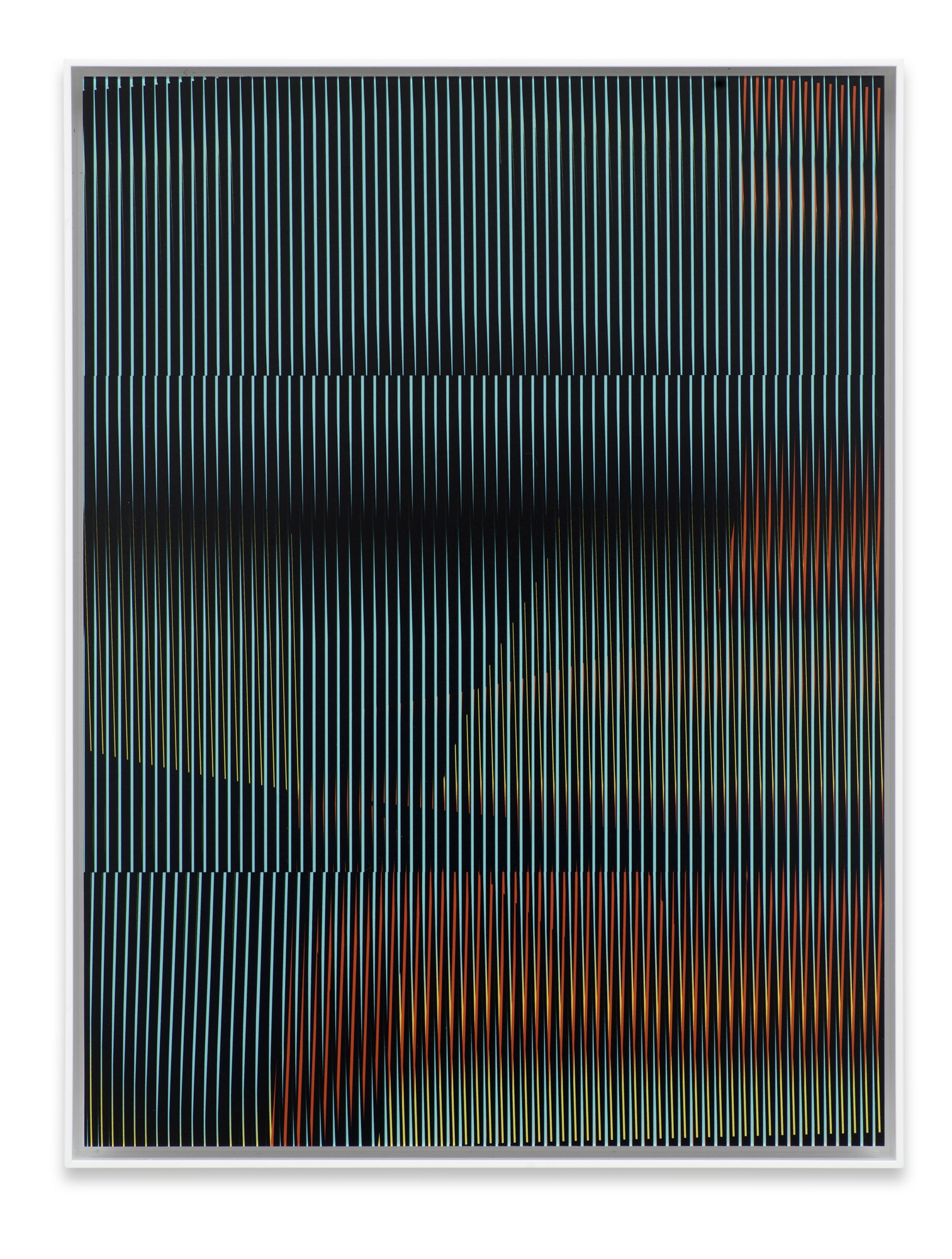

We can now translate that into immediate terms: to stand before an older or a more recent, a larger or smaller picture by Jörres (who has no use for work titles) is to find oneself incapable of letting one’s perceptions come to a rest. The plateaus of superimposed and intermeshed visual planes seem charged with an intangible dynamic energy that manifests as white noise and flickering. Moiré effects of the sort the artist has long employed have historic antecedents in the practices of Bridget Riley, François Morellet, or Carlos Cruz-Diez; working in different contexts, they created similar situations in the early 1960s that pushed the psycho-physiological capacity of eye and brain to edges where two-dimensional image and three-dimensional space blurred into one another. Nowadays, the ambient visual noise of Jörres’s pictures between abstraction and image interference may stand for the residual resistance that art is allowed, and by extension, for pure and positive potentiality.

If the conceptual and minimal art of the 1960s challenged the heroism of painting while fostering a growing awareness of contexts, the 1990s may be understood as a period in which a minimal-abstract aesthetic forges a fresh alliance with social utopia and communitarianism after the fall of the Wall made political conceptions of collectivism obsolete. At the same time, phrases like “flood of images” appear on the scene in the wake of the rise of digital technology that will remain fixtures of the debates. Almost thirty years later—which is to say, now—an art market preoccupied with identity politics and ecological concerns is jolted by an auction result and once again turns to technology; this time it’s the NFT—the file-as-unique-copy.

2)

The most recent series of works by Jörres presented in this show is titled Kleine Bilder, Small Pictures, and compared to the artist’s earlier painterly output, the formats are indeed fairly modest. What You See Is What You Get: small pictures. Measuring 40 by 30 cm (15.7 by 11.8 in), they’re roughly the size of an average screen or flatbed scanner. In fact, the works were originally intended as designs for future execution in paintings. The idea dates back to the year 1997 and a Photoshop class Jörres took at the Maastricht Institute of Arts: it inspired him to produce sketches that resembled the pictures he has now realized. At the time, his teachers advised him against pursuing this avenue further, warning that it led outside the bounds of painting.

And let’s be honest: it’s not painting strictly speaking but C-prints that Jörres laminates onto aluminum Dibond panels and then mounts in standard-format frames behind acrylic glass. To generate the motifs, he runs open-source-software, no license required, on an older-model computer he bought used, an approach that harks back to the idealisms of the WWW’s early boom years. Specifically, he relies on two pieces of freeware: “Inkscape,” for the layout of the color-field lineaments in the pictorial planes he montages atop one another; and “Gimp,” a 1995 graphical postproduction program he uses to simulate the gestural traces of what look like screen-wiping motions. But—what kind of art are we actually dealing with in these works?

Not unlike the specific objects that Donald Judd launched as vehicles of a “tactical innovatory art criticism” (Klaus Jörres) in the 1960s, deftly occupying a new interstice between painting and sculpture, the Small Pictures are specific objects: neither painting nor photography but hybrids without a central organizing principle. The artist sources all components from suppliers, making the works quasi-readymades: the demand assessment, the design and planning process, and the supply chain management are all handled from Jörres’s desk in a kind of telework, as is the final assembly of the material. It strikes me as significant that the works can’t be taken apart again. That makes them almost the physical equivalents of NFTs—simulacra. The Latin word—the Greek counterpart is “eidolon”—denotes sheer images detached from the surface, holographic “doppelgangers” of what they represent whose agency unfolds in the twilight zone between subject and object, between thing and beholder. Not coincidentally, the word “film” has its origins in a similar context. If we read Jörres’s Small Pictures as simulacra, they capture, within a world steeped in technology, the gruffly poetic quality of a new interstice bridging design and product.

As the Wikipedia entry on “Inkscape” notes, the program came into being in 2003 as a code fork[1] of the vector graphics editor “Sodipodi”; the split was prompted by “differences over project objectives” and the development process.[2] Around the same time, Klaus Jörres’s work, too, appears to inch away from conformity to the global pop-culturalization of contemporary art, an inflation of creative classes that parallels the novel fusion of finance economy and communication technology—in a word: from growth. True, Jörres, too, started to depend on participant observation to pay the bills; then again, Robert Ryman, to name one example, made ends meet in his early years by working as a night guard at the MoMA. In his own work, Jörres has remained both consistent and frugal, though the latter in part not by choice. His art takes a skeptical stance, distrustful not only of the expressive register but of any idea of heroism, any pioneering spirit. His preferred field is the domain of the norm, the general—of work or, more properly, production itself as an inner refuge from too much expression.

This practice has not only allowed him to compile a repository of future pictures as a hedge against potential pressures to engage in just-in-time production; more importantly, his long-term time management—consciously modeled, in a gesture of self-assurance, on Duchamp—enables him at this particular time to cite, with unimpeachable credibility, historic junctures at which wrong turns may have been taken: realizing an idea from 1997 in 2022—Small Pictures as iridescent yet timeless anti-monuments to our present moment, in which the lived and built world, defying all desires for resonance, care, and participation, fluidly plays out between the ones and zeros of the processors. That suggests one last question: what are we to make of a career like Jörres’s, whose expansion has been more gradual and circumspect, in light of the discourses around the post-growth society? And the answer, dear reader, is up to you.

Martin Germann is a writer and exhibition maker and lives and works in Cologne. He is an adjunct curator for the Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, and a curatorial advisor to the upcoming 2022 Aichi Triennale. From 2012 until 2019, he led the art department at S.M.A.K, Ghent, after working as a curator at the Kestner Gesellschaft, Hannover, from 2008 until 2012. He also worked on the 3rd and 4th Berlin Biennials of Contemporary Art. He teaches and publishes on a regular basis and is a board member of Établissement d’en Face, Brussels, and serves on the acquisitions committee at IAC Villeurbanne.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fork_(software_development).

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inkscape.