10TH LECTURE AT THE GRAMSCI MONUMENT, THE BRONX, NYC: 10TH JULY 2013 ANTIGONE’S BEAUTY MARCUS STEINWEG

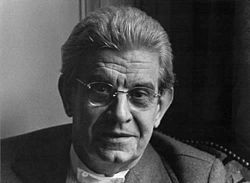

Jacques Lacan

As headless as this crazy child may be: Antigone is aware of her own precision. Consistently she overhears Ismene's voice, representing the general doxa. What speaks through Ismene is established reason. Ismene knows nothing but caution, contemplation, comparison. Antigone, however, verges on the delusion of the subject. Her beauty, as Jacques Lacan described it, lies in her insistence and her idleness, leading towards the threshold of her life.

More than merely its end, this edge marks the evidence of the antigonist subject. Lacan addressed it as Antigone's reverberation, as éclat, which might be translated as glamour and scandal. What is essential is that a boundary is overstepped, initially that of the law represented by Creon, which prohibits the burial of her brother Polynices. And yet, this transgression cannot lead into a positive realm beyond the edge. Antigone in no way exemplifies the subject of a romanticism of transgression, which successfully eludes the established rule of law in order to exist in virtually full autonomy: we know that a dismal rock cut tomb awaits Antigone. By responding to Creon in his own language, the „language of the state“, or as we may say, reality, Antigone's politics is, according to Judith Butler, „not of oppositional purity but of the scandalously impure.“ She „asserts herself through appropriating the voice of the other, the one to whom she is opposed; thus her autonomy is gained through the appropriation of the authoritative voice of the one she resists, an appropriation that has within it traces of a simultaneous refusal and assimilation of that very authority.“ If autonomy exists – an infinitesimal quantum of autonomy – then only as a claim in the midst of real heteronomy.

One cannot help but to compromise oneself. One is already compromised. No subject is ever intact (or, as Adorno puts it: „None is tabula rasa.“). There is no integrity untouched by the facts. The incommensurable measure of freedom, which Antigone allows herself despite Creon, articulates itself only in relation to him and the authority represented by him, i.e., the authority of the effective law: the „law of the day“ (of the polis, the constituted reality), which has been contrasted with the „law of the night“ (of gods, family, Hades).

The antigonistic desire is desire for autonomy, embedded into the heteronomous, an autonomy from this world, if you will, one turned towards the heteronomous as the mundane nomos. Something like self-determination can only exist with a window towards heteronomy, in the here and now of codified reality. Freedom is readable only in relation to objective non-freedom, sovereignty is nothing but a mode of the factual lack of sovereignty.

„We will“, Jean-Luc Nancy once said, „not oppose autonomy with heteronomy, with which it forms a pair. Being heteronomous toward another subject that is itself autonomous changes nothing, regardless of whether this other autonomous thing is named god, the market, technics, or life. But, in order to open a new path, we could try out the word exonomy. This word would evoke a law that would not be the law of the same or of the other, but one that would be unappropriate by either the same or the other. Just as exogamy goes outside of kinship, exonomy moves out of the binary familiarity of the self and the other.“ Instead of rejecting the realities given, Antigone relates to them by objecting to them. At the very threshold of the law she insists on the threshold. She does so beautifully (and gracefully and sexily): she withdraws from both the assimilation to the extant and the sublimation into the beyond. She takes on the burden of the threshold, as if she knew that, in doing so, she opens herself up towards the unliveable and her death.

Now one cannot sacrifice one's life to the unliveable without being a lofty idiot. The philosophical perspective into which the antigonistic subject puts itself is not transcendence. It's neither about higher values nor about a divine law superior to a human one. It's not even about a childish heroism, or, as we would say today, about narcissistic radical chic. It is about the cleft dividing each and every subject: into subject and object, into a spontaneous agent and a perceptive receptor, into an animal ensnared in its immanence and a vector penetrating this immanence. Antigone moves on a level of a certain immanence perforated by immanent trancendence. This is the frail ground of a reality expanded by its incommensurable parts. Everything about her, her desire, her certainties and uncertainties, happens in the here and now of a world without any ultimate consistency. However, this world without outcome is no determined space. It is equipped with an instability, which reassures the subject in its own inconsistency. What could this inconsistency indicate but the evidence/truth of the subject, as not being completely the object of a web of determinants? Could Antigone's evidence lie in this non-idealistic conception of freedom: in a claim of freedom, which runs through all the stages of objective non-freedom? There is the appeal for a certain kind of resistance and freedom connected to Antigone. Antigone barricades herself from the established order, in order to instist on her own head, head- and reckless as this might seem. Antigone's evidence lies in her acceleration towards non-sense, which constitutes the truth of her situation. „Evidence refers to what is obvious, what makes sense, what is striking and, by the same token, opens and gives a chance and an opportunity to meaning. Its truth is something that grips and does not have to correspond to any given criteria. Nor does evidence work as unconcealment, for it always keeps a secret or an essential reserve: its very light is reserved, and its provenance.“ The fascination with Antigone is related to this light, this evidence, which obscures its sense by „casting different lights on the familiar“, as Adorno calls it, or, as Wittgenstein says, „throwing new light on the facts.“

A truth which does not need to correspond to given criteria can only be a lawless truth. Blind or headless truth to which a child spiralling out of control commits. A truth founded not on any knowledge, which therefore remains unproven and unjustified. That's what we call evidence: an unfounded, abysmal, dark truth, like the truth of love or passion. There are things like precise passions, which draw their conclusiveness from their own unfoundedness. Not because they were arbitrary, but because they intervene with the reality of the subject with a momentum which forces this reality to redefine itself. The experience of philosophy connects the experience of art with the antigonistic opening towards evidences, which obscure the established model of reality in order to newly expose or re-expose it.