Michel Houellebecq

Quatrains

15 Sep - 03 Nov 2018

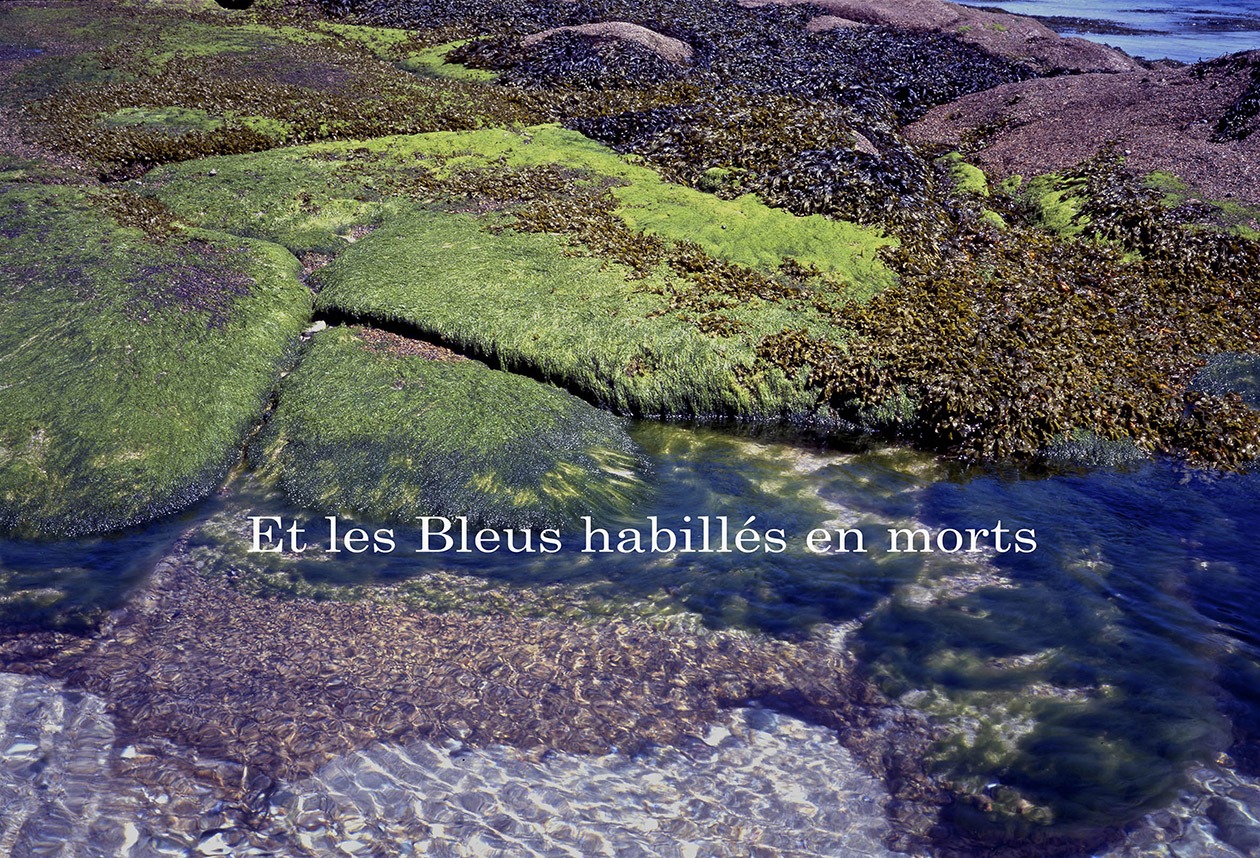

Inscriptions#010, extrait d'un diptyque, tirage pigmentaire (2016) sur papier Baryta contrecollé sur Dibond.

MICHEL HOUELLEBECQ

Quatrains

15 September - 3 November 2018

For Michel Houellebecq the first and most important operation consists in homing in on and marking out a segment of the world, an entity that denies externality and rejects the out-of- frame. The image then becomes a part of the world that is the world in its entirety. In the same way, poetry for Houellebecq is a totalising discourse. The verse is a word, a new, unsunderable unit, a complete, self-sufficient, indivisible whole with its own internal logic and beauty, beyond the realm of ideas. As Houellebecq has often put it, there is no such thing as an intelligent poet. The other operation consists in isolating and juxtaposing verse and image; in creating indissociable totalities out of separate elements; in implying that the poem is a discovery of preexisting words and this photographed fragment of the world something that had been waiting to be found: this grey, bleached-out beach, empty sky, motionless rock, cold blue surface. For his first exhibition at Air de Paris, Houellebecq has established, as always, a structure. We need to believe in structure, which protects us from suffering and loss: a narrative structure vaguer than that of the novel and close to that of his collections of poems 1 , from which he has extracted quatrains of the octosyllables and alexandrines that are the most traditional forms of French versification. He has often stressed the importance in his compositional process of the precision of these ancient metres and of regularity of rhythm. Brief and fully achieved, the verse is brought to the wall as image – but also given expression in the three songs from the Présence humaine album produced with Bertrand Burgalat on the Tricatel label in 2000. The poems, declaimed with diction that is clear and sharp, help fix the tonality of the rooms, generating a montage, an orderly continuity between the flat surfaces and things that exist in their own right. The song Présence humaine lays bare a typically «Houellebecquian» post-apocalyptic landscape. We recall the one at the end of The Possibility of an Island and the triumph of poetry over the novel, that reminder of the ongoing obsession, dating from his youth and his discovery of Lovecraft, with places seemingly vestiges of human transit. Then we branch off towards another more organic, biological, vegetal world, in macroscopic visions of the power and abstract beauty of reality, of its immanent ambiguity. The same abstraction was sought by experimental biologist Jean Painlevé in microphotography which culminated, late in his life, in a mind-blowing psychedelic film also on show here as part of another exhibition: the poetry of Liquid Crystals (1978) also derives from meticulous description of nature and a theory of measurement, light, colour and forms. With François de Roubaix’s score playing a core, guiding role. In mid-voyage, between these different worlds, is a solitary image, a brutal, sunstruck rupture: the dazzling vision of a road to infinity inscribed with the words «Nous avions des moments d’amour injustifié» («We enjoyed moments of unjustified love»). The most beautiful love song, Crépuscule , accompanies this revelation: in the midst of despair can be found the possibility of an eternal landscape, a «painless, noiseless crossing» that conjures up an inaccessible idea of happiness, a state of consciousness Houellebecq defines as «oceanic» and in which love unveils a new physics.

Stéphanie Moisdon

1 La poursuite du bonheur (1991), Le sens du combat/The Art of Struggle (1996) Paris, éditions Flammarion and Non-réconcilié/Unreconciled (2014) Paris, éditions Poésie/Gallimard.

Quatrains

15 September - 3 November 2018

For Michel Houellebecq the first and most important operation consists in homing in on and marking out a segment of the world, an entity that denies externality and rejects the out-of- frame. The image then becomes a part of the world that is the world in its entirety. In the same way, poetry for Houellebecq is a totalising discourse. The verse is a word, a new, unsunderable unit, a complete, self-sufficient, indivisible whole with its own internal logic and beauty, beyond the realm of ideas. As Houellebecq has often put it, there is no such thing as an intelligent poet. The other operation consists in isolating and juxtaposing verse and image; in creating indissociable totalities out of separate elements; in implying that the poem is a discovery of preexisting words and this photographed fragment of the world something that had been waiting to be found: this grey, bleached-out beach, empty sky, motionless rock, cold blue surface. For his first exhibition at Air de Paris, Houellebecq has established, as always, a structure. We need to believe in structure, which protects us from suffering and loss: a narrative structure vaguer than that of the novel and close to that of his collections of poems 1 , from which he has extracted quatrains of the octosyllables and alexandrines that are the most traditional forms of French versification. He has often stressed the importance in his compositional process of the precision of these ancient metres and of regularity of rhythm. Brief and fully achieved, the verse is brought to the wall as image – but also given expression in the three songs from the Présence humaine album produced with Bertrand Burgalat on the Tricatel label in 2000. The poems, declaimed with diction that is clear and sharp, help fix the tonality of the rooms, generating a montage, an orderly continuity between the flat surfaces and things that exist in their own right. The song Présence humaine lays bare a typically «Houellebecquian» post-apocalyptic landscape. We recall the one at the end of The Possibility of an Island and the triumph of poetry over the novel, that reminder of the ongoing obsession, dating from his youth and his discovery of Lovecraft, with places seemingly vestiges of human transit. Then we branch off towards another more organic, biological, vegetal world, in macroscopic visions of the power and abstract beauty of reality, of its immanent ambiguity. The same abstraction was sought by experimental biologist Jean Painlevé in microphotography which culminated, late in his life, in a mind-blowing psychedelic film also on show here as part of another exhibition: the poetry of Liquid Crystals (1978) also derives from meticulous description of nature and a theory of measurement, light, colour and forms. With François de Roubaix’s score playing a core, guiding role. In mid-voyage, between these different worlds, is a solitary image, a brutal, sunstruck rupture: the dazzling vision of a road to infinity inscribed with the words «Nous avions des moments d’amour injustifié» («We enjoyed moments of unjustified love»). The most beautiful love song, Crépuscule , accompanies this revelation: in the midst of despair can be found the possibility of an eternal landscape, a «painless, noiseless crossing» that conjures up an inaccessible idea of happiness, a state of consciousness Houellebecq defines as «oceanic» and in which love unveils a new physics.

Stéphanie Moisdon

1 La poursuite du bonheur (1991), Le sens du combat/The Art of Struggle (1996) Paris, éditions Flammarion and Non-réconcilié/Unreconciled (2014) Paris, éditions Poésie/Gallimard.