Jonas Burgert

06 Sep - 08 Nov 2008

Hamburger Bahnhof

Jonas Burgert

Jonas Burgert divides the artistic community. In one camp, devoted fans consider that after long years of theoretical overload they have been vindicated in their conception of art as sensory experience beyond the reach of logic; in the other, entrenched opponents see art’s reversion to historicist and diffusely psychologistic allusions as a betrayal of Modernism.

Unquestionably, art with history in its rear-view mirror has arrived. Setting the pace is Neo Rauch, who – rather in the spirit of the Renaissance – stylizes the ruins of a socialist world slumped in melancholy decay, with aimlessly roaming figures that do not belong to it, and Jonathan Meese, who deploys the trash of history with its gory myths, power players and spiritual heroes as the stage on which his cryptic scenes are enacted. And then there are the many contenders haunting the borders of kitsch to invoke nostalgia and the romantic beauty of bygone days – reduced in Matthias Weischer’s case to the elegiac simplicity of his depiction of interiors. In a sense, all this is appropriation art, which – after the borrowings from/adaption of modern everyday culture by artists like Jeff Koons, Richard Prince and Barbara Kruger – now has recourse to historical and art-historical topics/facets/issues long believed to have been definitively discarded.

This, then, is more or less the starting basis – and approximation is inevitable, given the diversity of postmodernist thinking – when focusing on the art of Jonas Burgert. He is a protagonist of an approach which studiously avoids reference to current issues in society and cultural theory thereby actually drawing attention to them.

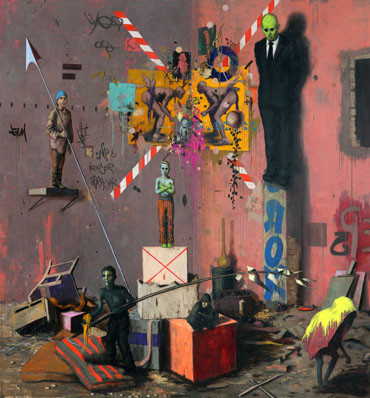

In his catalogue essay accompanying the Geschichtenerzähler [Storytellers] exhibition at the Hamburger Kunsthalle (2005), Christoph Heinrich suggests that to appreciate Jonas Burgert one needs to be a lover of opera, of that intricate web of music and words, visuals and atmosphere and character and emotion, born on the cusp between Renaissance and Baroque, a public event in which people sing at each other as they wage war, and pontificate endlessly on what is moral, or on Ultimate Truths. I have no problem with opera being pigeonholed between Renaissance und Baroque, nor with the notion that Jonas Burgert – comparable here with Meese but unlike Rauch – is seeking to free up a space for his own performance. But I do find it strange that Heinrich here adduces opera at all. Turning away as it does from the worldly to the sublime, and actually originating in the period round 1600, opera as I understand it is a Baroque form of expression. Burgert’s work picks up on strands of Late Renaissance thought, particularly Mannerism, from the end of the 15th and the 16th century, and on the work of the principal artists concerned: Hieronymus Bosch, Pieter Brueghel the Elder and El Greco, all of whom brought the Dionysian principle of a chaotic, orgiastic universe into direct confrontation with the Apolline values of the classical Renaissance. The grotesque, the distorted, the gestic provide the subject-matter of this art; the stages on which it plays are the commedia dell’ arte and the Carnival. The principal roles in it go to the garrulous and the wily, victims and villains, the downtrodden, the guilt-ridden and the wretched, demons, harlequins, fools, animal-humans and human-animals. And the two principal dramas constituting the repertoire of this theatrum mundi of an inverted, topsy-turvy world are: the Apocalypse and the Last Judgment.

Jonas Burgert is not a history painter, and his studies of the grotesque are not social criticism. It was some time ago that the grotesque came forward from its original position on the margins, as counter-culture, to occupy the centre of a society in love with spectacle, there to be taken over completely and become the property of inscrutable hierarchies and exploitative systems. The artist’s œuvre as a life’s work? – forgotten. Artists of today’s generation see themselves as the cool-headed strategists behind the operating system Art, that regard the new no longer as the utopia of a better and juster world, but as a criterion of the success of a global culture industry, with its art fairs and auctions month after month, over 50 biennales and triennales, and its plethora of touring exhibitions on view at museums and exhibition centers. The artists conform to the trends or resist them – which of course is when they become sought-after victims.

It is not possible to detach Burgert’s work from its context in the art business, and yet the artist himself seems unimpressed. He is without hang-ups, easygoing, has a pleasant manner and plenty of self-confidence, and could not care less about marketing strategies or the emotions of people who look at his pictures. His anachronistic references to the wild fantasies of the grotesque have put him in a position to run his affairs at a distance from the current debate on social practice. He represents a young generation which repudiates our society’s pressure for functional conformity and success, withdrawing instead into worlds that it defines for itself. Burgert made his decision on artistic grounds, and on that account the pronouncement in the Book of Revelation may set him in perspective: “So then because thou art lukewarm, and neither cold nor hot, I will spue thee out of my mouth.” Lukewarm Jonas Burgert emphatically is not; his internal thermostat (to adapt a remark made by Werner Büttner about his friend, that exemplar of an outsider, Martin Kippenberger) lacks an intermediate setting.

Harald Falckenberg (first published in: Jonas Burgert, exhibition catalogue, Produzentengalerie Hamburg, 2006)

Jonas Burgert

Jonas Burgert divides the artistic community. In one camp, devoted fans consider that after long years of theoretical overload they have been vindicated in their conception of art as sensory experience beyond the reach of logic; in the other, entrenched opponents see art’s reversion to historicist and diffusely psychologistic allusions as a betrayal of Modernism.

Unquestionably, art with history in its rear-view mirror has arrived. Setting the pace is Neo Rauch, who – rather in the spirit of the Renaissance – stylizes the ruins of a socialist world slumped in melancholy decay, with aimlessly roaming figures that do not belong to it, and Jonathan Meese, who deploys the trash of history with its gory myths, power players and spiritual heroes as the stage on which his cryptic scenes are enacted. And then there are the many contenders haunting the borders of kitsch to invoke nostalgia and the romantic beauty of bygone days – reduced in Matthias Weischer’s case to the elegiac simplicity of his depiction of interiors. In a sense, all this is appropriation art, which – after the borrowings from/adaption of modern everyday culture by artists like Jeff Koons, Richard Prince and Barbara Kruger – now has recourse to historical and art-historical topics/facets/issues long believed to have been definitively discarded.

This, then, is more or less the starting basis – and approximation is inevitable, given the diversity of postmodernist thinking – when focusing on the art of Jonas Burgert. He is a protagonist of an approach which studiously avoids reference to current issues in society and cultural theory thereby actually drawing attention to them.

In his catalogue essay accompanying the Geschichtenerzähler [Storytellers] exhibition at the Hamburger Kunsthalle (2005), Christoph Heinrich suggests that to appreciate Jonas Burgert one needs to be a lover of opera, of that intricate web of music and words, visuals and atmosphere and character and emotion, born on the cusp between Renaissance and Baroque, a public event in which people sing at each other as they wage war, and pontificate endlessly on what is moral, or on Ultimate Truths. I have no problem with opera being pigeonholed between Renaissance und Baroque, nor with the notion that Jonas Burgert – comparable here with Meese but unlike Rauch – is seeking to free up a space for his own performance. But I do find it strange that Heinrich here adduces opera at all. Turning away as it does from the worldly to the sublime, and actually originating in the period round 1600, opera as I understand it is a Baroque form of expression. Burgert’s work picks up on strands of Late Renaissance thought, particularly Mannerism, from the end of the 15th and the 16th century, and on the work of the principal artists concerned: Hieronymus Bosch, Pieter Brueghel the Elder and El Greco, all of whom brought the Dionysian principle of a chaotic, orgiastic universe into direct confrontation with the Apolline values of the classical Renaissance. The grotesque, the distorted, the gestic provide the subject-matter of this art; the stages on which it plays are the commedia dell’ arte and the Carnival. The principal roles in it go to the garrulous and the wily, victims and villains, the downtrodden, the guilt-ridden and the wretched, demons, harlequins, fools, animal-humans and human-animals. And the two principal dramas constituting the repertoire of this theatrum mundi of an inverted, topsy-turvy world are: the Apocalypse and the Last Judgment.

Jonas Burgert is not a history painter, and his studies of the grotesque are not social criticism. It was some time ago that the grotesque came forward from its original position on the margins, as counter-culture, to occupy the centre of a society in love with spectacle, there to be taken over completely and become the property of inscrutable hierarchies and exploitative systems. The artist’s œuvre as a life’s work? – forgotten. Artists of today’s generation see themselves as the cool-headed strategists behind the operating system Art, that regard the new no longer as the utopia of a better and juster world, but as a criterion of the success of a global culture industry, with its art fairs and auctions month after month, over 50 biennales and triennales, and its plethora of touring exhibitions on view at museums and exhibition centers. The artists conform to the trends or resist them – which of course is when they become sought-after victims.

It is not possible to detach Burgert’s work from its context in the art business, and yet the artist himself seems unimpressed. He is without hang-ups, easygoing, has a pleasant manner and plenty of self-confidence, and could not care less about marketing strategies or the emotions of people who look at his pictures. His anachronistic references to the wild fantasies of the grotesque have put him in a position to run his affairs at a distance from the current debate on social practice. He represents a young generation which repudiates our society’s pressure for functional conformity and success, withdrawing instead into worlds that it defines for itself. Burgert made his decision on artistic grounds, and on that account the pronouncement in the Book of Revelation may set him in perspective: “So then because thou art lukewarm, and neither cold nor hot, I will spue thee out of my mouth.” Lukewarm Jonas Burgert emphatically is not; his internal thermostat (to adapt a remark made by Werner Büttner about his friend, that exemplar of an outsider, Martin Kippenberger) lacks an intermediate setting.

Harald Falckenberg (first published in: Jonas Burgert, exhibition catalogue, Produzentengalerie Hamburg, 2006)