SPATIAL IMAGES ARE THE DREAMS OF SOCIETY

In 1923, Murayama introduced what he called "conscious constructivism," which involved expressing modern life through non-objective forms in order to reintegrate art and daily life and eradicate elite "fine art." The constructivists believed that the work of art “was contained not in the representational quality of the picture, but in the pictorial elements themselves, in their mutual relationships and interaction, and that construction should be dynamic, based on ‘motion-producing asymmetry’” . The agenda of the Japanese Mavoists was the revitalization of everyday life through the intervention of an “art of the streets”. This practice lasted only for a few months and disappeared thereafter, and is only known today through black and white photographs, a few sketches, and descriptions by contemporary witnesses.

Ethnographical Reconstructions In the attempt to comprehend the phenomena surrounding the architectural framework of Tokyo in the 1920s, Thorsen turned into an ethnographer, studying the city’s historical background, its imagery and symbolism. She asks the questions: How are cultural, economic, and political parameters inscribed in urban, spatial, or architectural design? What can we do with it today?

Her starting point is built on extensive studies and field research, which enable her to gather a wealth of archive material. For the first exhibition of this project in Lüneburg, she produced a slide projection and two wall paintings at an early stage. The slide projection, “When I Walk on the Streets these Days, somehow I can‘t relax...” (2007), analyzes the original façades of the barrack decoration movement and the surviving photographs of them. Investigating a moment of architecture and design after an urban disaster, attention is drawn to the temporality of this architecture, to its performative façade and its radical, modern gesture. Form meets content in this installation as the layers of the slide projection record the layered structures of the façades. The layers include archive material of texts, photography, and drawings analyzing single elements of the façades. The drawings are especially important since they are a way of analyzing the inner structure of the single elements of the façades. Therefore, the resulting work consists not only of the reconstruction of the facts, but also emphasizes the different layers or overlays extracted from the architecture. Fragile lines, breaks, coincidences, and supposed "mistakes" in these drawings give rise to a poetic value, one that completes the analysis of the architecture by casting a glance on the people behind it. It is all about the "invisible" and physiological aspects of space as well as its impact on the people who move within this space.

The single elements of the slide show are morphed into each other, producing an animation that uses displacements, distortions, and the presence of time. The viewer takes the place of the artist and follows her way of understanding, step by step--from the texts explaining the Mavo movement to the original façades and the reconstruction of its layers. The drawings resemble the lines of a contour map, showing the basic modernist forms behind the architecture. It is the combination of narrative and structural coherence that leads to multi-layered poetic connotations accompanied by the effect of light and temporality through the utilization of a slide installation. Thorsen works with openness and eludes to a monolithic interpretation positing itself at once as a coming-of-age quest, a reflection on alter egos, or an adventurous experiment in both traditional and contemporary thinking. The paradoxical logic of utopian dreams meets constructivist architecture in such a dynamic way that it appears more real than reality itself.

The accompanying wall paintings showed and confronted the structure of the painted brick façades of medieval Lüneburg buildings with elements of a façade by the Japanese architect and painter Kato Masao, which is also shown in the slide projection. He exhibited a model of this design in June, 1923, a few months before the earthquake, and it clearly presents some of the forms that would have been executed in full scale in the barrack decorations a few months later. The connection to the painted façades from medieval times in the Lüneburg exhibition opened one’s eyes to a certain archetype in architecture, transporting the meaning and importance of illusion and desire. Colour had a key impact in the development of the project. In the beginning, this proved problematic in that all the documentation of the boldly coloured façades is only in black and white. Although the importance of colour in this architecture cannot be denied, it is almost impossible to track down the original chromatics. In the first show, Thorsen solved the problem by using a substitute in the form of a colour chart painted on one corner of the wall, referring to the painted facades initiated by Bruno Taut in Magdeburg between 1921 and 1923. The colours are also only partly known but are described in texts about Taut’s façades. Taut’s work in Magdeburg was well-published at the time, especially in Japan, where he briefly lived after 1933 and where he produced three influential books celebrating Japanese culture and architecture, comparing the historical simplicity of Japanese architecture with the modernist discipline. Kato Masao was inspired by Bruno Taut’s work, and the artists involved in the barrack decoration movement in Tokyo must have also had black-and-white reproductions and descriptions of his buildings in Magdeburg.

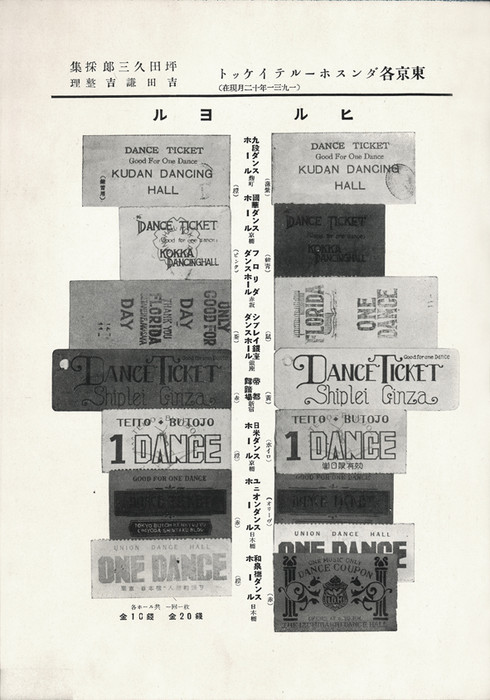

In the course of the project, Thorsen worked on different series of drawings (Façade, Tokyo, 2007) and gouaches (Colour Sample, Façade, 2009) that push the colour scheme even further. Starting out in black and white and treating the architecture in a reduced, figurative way, the works soon became abstract, combining basic forms with elements in colours. This finds its equivalent in the original façades. The kanban kenchiku (signboard architecture) consists mainly of a small insignificant building with an elaborate, coloured façade facing the street. Thorsen prescinds this architecture and identifies certain elements of the façade with colours, creating a two-dimensional ensemble of basic shapes which, from today's perspective, ties in with the modern abstract paintings of the 1920s. She highlights the exemplary character of the individual architectures: thus, the drawings and gouaches are partly related to still existing houses which evince the new architectural typology of the time. Chromatic juxtapositions emphasise the contrasts in the highly structured architecture in order to reinforce the hierarchically conceived character of the signboard architecture. In the slide installation, Tokyo March (2009), Thorsen, in four chapters related to the lyrics of a famous song for which the work is named, follows up on the layout drawings of the façades of the Ginza, the stage for modernity at that time. They were made between 1930 and 1931 by Kenkichi Yoshida, the artist, designer, and co-developer of Modernology, a theory defined as an indigenous, unprecedented study of modern customs and more. The drawings are an analysis of the existing façade compositions and focus particularly on commercial – Western as well as Japanese – typologies, which appeared in the form of neon signs, signboards, and shop windows, and which are made readable in an abbreviation. Similar to the later Pop art movement, commercial life was seen here as a feature, an experimental field, and a stage for modern life. With her camera, Thorsen zooms into these streets, takes details, enlarges them, reduces them again, showing graphic overlays as well as architectural details, which vary greatly. The second focal point of the slide installation further reassembles the photographic archive material, deciphering the meanings of the drawings. Thorsen breaks down the structures behind the abstraction in order to track down the architectural ideas behind this drawn row of houses. Only the individual architectural detail of the façade, singular and in itself significant, is in black and white, lit on the wall, doubling the concept of the façade. This complex image plane is not only a reconstruction of the facts, but makes the both readable and non-readable façade mutually interpretable. The pictures are so blended into each other that they set the architecture in motion. For the viewer, the drawings are depicted on the basis of the Situationists’ notion of dérive, a technique of rapid passage through varied ambiences. Dérives involve a playful-constructive behaviour and an awareness of psycho-geographical effects, and are therefore linked to the notion of fluidity with which the Mavo movement was very much concerned. Theatricality ”Murayama called architecture ‘theatrical art exposed to the street.’” Hailed as the "first constructivist stage designer" in Japan and esteemed for his producing and writing for the theatre, the closeness of signboard architecture to stage design does not come as a surprise. Favoured by Western avant-garde movements as well, the reasons for this are, according to Weisenfeld, that “The theatrical, at its most effective, challenged the deceptive transparency of naturalistic representation by replacing it with a self-reflexive construction.” The Mavo artists considered theatre and dance to be worthy areas for artistic experimentation, not least because they relied on audience response. They wanted to transform the street into a stage for theatricalizing artistic practice, converging concerns regarding design, theatre, and socio-political. Architecture is viewed as an image, as well as a stage for the imaginary, with its varying enrolments and projections, thus referring to the constructed character of reality. The designed space in particular is always a political space that implies certain norms, values, and relationships combined with intrinsic longings and visions that are acted out. The basic elements of expressionist theatre are dance, mime, gesture, colour, line, and rhythm. It is interesting to see how these elements are integrated into the scenario that Sofie Thorsen is building up in her installations and single works. She does not only document what she has gathered together, but she arranges these elements in such a poetic way that the installation becomes a stage of its own. The rhythm of the slides, the specific usage of colour and light, and the abstract architectural elements of the drawings and the gouaches come together in a dense installation in which the presentation and representation of a given topic lead to a self-reflexive mediation and the activation of the viewer. Her concern with the appropriate form follows the discourse of the 1920s, but at the same time, actualizes it. By formulating a certain aesthetic discourse, a socio-political agenda is put on stage. The Mavo combined “modernist aesthetic concerns about autonomous expression and anarchist concerns about rebellion against the status quo” in a period of transition in Japanese culture. Considering that nowadays, we are currently facing our own period of transition, this is exactly what modernism can teach us today. The productive forces and ideas of artistic and architectural modernism, to which many would be only too happy to bid farewell, raise inevitable questions since they represent the cornerstone of today's cultural and social models. A harsh critic of modernity, Kracauer, who complained about its emptiness of meaning and transcendental homelessness, stated that “Ratio is cut off from reason and bypasses man as it vanishes into the void of the abstract” . He was not critical of rationality per se but believed that is had been robbed of its progressive potential. Thorsen seems to revive this progressive potential and neglects the void of the abstract quite successfully. She examines modernism in so far that Japanese modernism is not to be mistaken as a friendly takeover of Western modernism. Japanese modernism started out as an adaptation of Western modernism then became a translation and developed its own particular language and its own specific meanings from it. Thorsen tries to understand the differences of the Japanese way. It is like oscillating between the familiar and the exotic, constantly trying to understand the given images which are the main source of information. This ongoing attempt to see and understand while still being aware of not being able to grasp the whole “picture” allows her to try to fill the void that Kracauer criticised. The void might still be there in the end, but questions that are posed regarding perception lead to a contemporary version of what modernism might mean for us today.

Perception

In the short film, Achromatic islands, Thorsen extends the subject beyond the specific era of the 1920s in Japan. Depicting the contemporary landscape of the Danish island of Fur, the film functions less as a window onto a grand illusion than as a medium of reflection on the potentialities of perception. Thorsen turns her attention towards a special set of problems in this peripheral area: up until the 1950s, a genetically inherited strain of black-and-white colourblindness prevailed among the inhabitants of the secluded island, but has disappeared since then with the gradual opening-up of the isolated area. The principle of the film is based on a kind of decomposition of scenes that forms striking interstices. The images are separated from the narrator’s account, becoming symbolic allusions instead. In this way, the viewer is interpolated between the scenes and is invited to make sense of the scenario for him or herself. This can be compared with the works about urban space that each, in their own way, deal with our movements in urban space and the experiences we have as a result. The images and words in the film sound distant and strange. In the end, they are removed from reality, becoming projections, in the psychological sense of the word, mirrors of the Other as well as fictions that can be invested, explained, and interpreted in terms of the viewer’s own perceptions.

Every step through this series of works reveals new aspects. Thorsen – in a sensitive and focused way - constantly pieces things together, finding fragments of information, splicing them, collaging them, and montaging them in order to create a network of perceptions. Following the metaphor of colourblindness, her work is about each person’s own way of seeing. Sometimes, what is seen is not what is seen. Each product of formal design or architecture embodies the utopia of a space in which this utopia appears in an ideal way as a dream of society. Just as Japan's Jazz Age was a brief period of intense debate, curiosity, openness, and architectural and artistic freedom, this scenario could function as a perfect metaphor for opening up a new discourse.

Bettina Steinbrügge

Literatur:

Siegfried Kracauer, “On Employment Agencies”, in Rethinking Architecture, (London: Routledge 1997), p. 60.

Janet Koplos, “Japan’s jazz-age avant-garde”, Art in America, November 2002

Miriam Silverberg, “Constructing the Japanese Ethnography of Modernity”, in The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 51, No. 1 (February 1992), pp. 30-54, p. 33.

Stephen Mansfield, Tokyo: A Cultural History, Oxford University Press, p. 172ff

Miriam Silverberg, “Constructing the Japanese Ethnography of Modernity”, in: The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 51, No. 1 (Feb., 1992), pp. 30-54, p. 33.

Janet Koplos, “Japan’s jazz-age avant-garde”, Art in America, November 2002

Gennifer Weisenfeld, Mavo: Japanese artists and the avant-garde 1905-1931, Berkeley: University of California Press 2002, p. 218.

Gennifer Weisenfeld, Mavo: Japanese artists and the avant-garde 1905-1931, Berkeley: University of California Press 2002, p. 245.

Siegfried Kracauer, The Mass Ornament, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press 1995, p. 84.