Cheyney Thompson

Toolpaths for Bellona

27 Apr - 02 Jun 2018

CHEYNEY THOMPSON

Toolpaths for Bellona

27 April – 2 June 2018

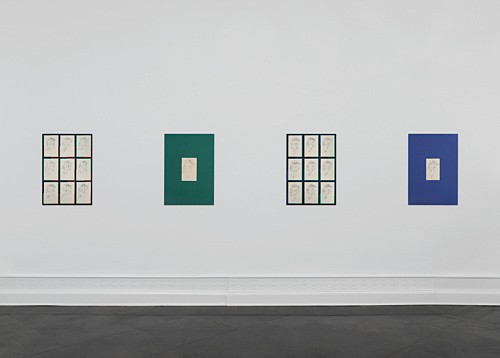

I am returning to these ten Cézanne drawings without knowing exactly what draws me back to them so frequently. They are studies after the figure of Bellona in the Rubens painting ‘Apotheosis of Henri IV’ which hangs in the Louvre. Cézanne made them over a thirty year period presumably while visiting the museum. Fifteen years ago, I was trying to make sense of something Cézanne or Gasquet said about his desire to become “a sensitized plate.” I think, for a little while, it helped me sketch out a tense historical sequence passing through Bézier, Casteljau, Citroën, Renault, a woodworkers strike, automation, labor. Something stillborn setting into motion so much mourning. A problem of prehension, the appearance of some technologies, the camera, which laid siege to the entirety of the corporeal regime of sensation. Nothing sudden about it, already the museum was there and the painting was there, asserting a syntax (there were other Bellonas, other figures), some images of some bodies. Cézanne, always returning to the museum and always leaving, taking notes, only to return again to the same images. Seen from above, trajectories, not unlike Fernand Deligny’s drawings after his autistic comrades, could emerge like a tangle of GPS data. A trace that communicates nothing, or very little. I saw this, but not even. Now, two drawings for everyone. Going to the museum, picking up the pencil, putting away the pencil, leaving the museum, going somewhere else, all these toolpaths. And collections, a collection of paintings, a collection of gestures, a collection of names, of bodies, a collection of lines, a collection of pathways. I can count all the lines in the collection, ten bundles of lines, each bundle ranging from one thousand seven hundred and twelve in the largest collection to two hundred and seventy in the smallest.

The bundles are always organized around the same form of Bellona. The internet tells me she was a Roman goddess of war and that some people cosplay as her, or some version of her, there are enough versions of her around that the Warburg Institute has a file on her. The bundles also have differing distributions of short or long lines and light or dark lines. The lines are themselves bundles of dimensional points, amplitudes, tangents... For the ten bundles, there are forty-five ways that the ten collections can be combined. This is found from a combinatorial operation called n choose two. By this same simple function, the forty-five will later become nine-hundred and ninety and a third generation becomes four-hundred-eighty-five-thousand-five-hundred-fifty-five. I learned from a friend that there are other functions that get you into the realm of large numbers quickly, for example the Ackerman function or the Busy-Beaver function. But I liked this one because it allowed me to imagine these Bellona’s as an isolated tribe of hermaphrodites suffering under the pains of an imperative to reproduce through singular pairings. In order for the merging of two collections to take place it was necessary to find a technique that allowed for a temporary elimination of the uniqueness of each line in each drawing. From one point of view this is sublation, from another it is compression.

A bin lattice is placed over the drawings whose addresses are organized following a Hilbert curve. Now, local densities in the tangles can be meaningfully evaluated across the collection. After this cleansing ritual is complete, it is no longer necessary to talk about thighs or breasts or elbows. The clustering algorithm copy and pasted from Github takes over, and even though big data seems to like it, someone on the stackoverflow boards refers to it as a ‘garbage in garbage out’ algorithm. I like it because trying to understanding it conjures an image of a handful of stones being tossed into a still lake. The ripples converge as a collection of cells. Voronoi cells, Benard cells, at the heart of self-organization there is very clearly no self to be found and maintained, only the bleeding out of scalar values that momentarily slide into a dimensional array. Just some feature vectors looking for an object. But for these drawings it will have to suffice, it is already more than enough for the robot to get to work.

C.T.

“Cheyney Thompson has made the technology, production, and distribution of painting the subject of his work for over a decade. Thompson employs rational structures, technological processes, and generative devices as part of ‘thinking through problems that organize themselves around the terms of painting’. With such a rigorous approach to the medium, he has produced visually engaging yet exacting work that addresses varieties of abstraction including pictorial, economic, and technological. The status of painting within competing technological modes of image production and the medium’s historical and technical conditions have been central concerns in much of Thompson’s recent work. As a technology, painting is both outmoded within the technics of the production and circulation of images, yet also able to continuously incorporate and internalize other technical modes of production. Thompson’s paintings readily engage the image, as mediated by precisely such a series of technologies – from perspective and photography to the cinematic apparatus and the digital artifact. [...]”

Excerpt from: João Ribas, in Metric Pedestal Cabengo Landlord Récit, MIT List Visual Arts Center, Cambridge 2013

Toolpaths for Bellona is the sixth solo exhibition by Cheyney Thompson at Galerie Buchholz. Cheyney Thompson (born 1975 in Baton Rouge) lives and works in New York.

Toolpaths for Bellona

27 April – 2 June 2018

I am returning to these ten Cézanne drawings without knowing exactly what draws me back to them so frequently. They are studies after the figure of Bellona in the Rubens painting ‘Apotheosis of Henri IV’ which hangs in the Louvre. Cézanne made them over a thirty year period presumably while visiting the museum. Fifteen years ago, I was trying to make sense of something Cézanne or Gasquet said about his desire to become “a sensitized plate.” I think, for a little while, it helped me sketch out a tense historical sequence passing through Bézier, Casteljau, Citroën, Renault, a woodworkers strike, automation, labor. Something stillborn setting into motion so much mourning. A problem of prehension, the appearance of some technologies, the camera, which laid siege to the entirety of the corporeal regime of sensation. Nothing sudden about it, already the museum was there and the painting was there, asserting a syntax (there were other Bellonas, other figures), some images of some bodies. Cézanne, always returning to the museum and always leaving, taking notes, only to return again to the same images. Seen from above, trajectories, not unlike Fernand Deligny’s drawings after his autistic comrades, could emerge like a tangle of GPS data. A trace that communicates nothing, or very little. I saw this, but not even. Now, two drawings for everyone. Going to the museum, picking up the pencil, putting away the pencil, leaving the museum, going somewhere else, all these toolpaths. And collections, a collection of paintings, a collection of gestures, a collection of names, of bodies, a collection of lines, a collection of pathways. I can count all the lines in the collection, ten bundles of lines, each bundle ranging from one thousand seven hundred and twelve in the largest collection to two hundred and seventy in the smallest.

The bundles are always organized around the same form of Bellona. The internet tells me she was a Roman goddess of war and that some people cosplay as her, or some version of her, there are enough versions of her around that the Warburg Institute has a file on her. The bundles also have differing distributions of short or long lines and light or dark lines. The lines are themselves bundles of dimensional points, amplitudes, tangents... For the ten bundles, there are forty-five ways that the ten collections can be combined. This is found from a combinatorial operation called n choose two. By this same simple function, the forty-five will later become nine-hundred and ninety and a third generation becomes four-hundred-eighty-five-thousand-five-hundred-fifty-five. I learned from a friend that there are other functions that get you into the realm of large numbers quickly, for example the Ackerman function or the Busy-Beaver function. But I liked this one because it allowed me to imagine these Bellona’s as an isolated tribe of hermaphrodites suffering under the pains of an imperative to reproduce through singular pairings. In order for the merging of two collections to take place it was necessary to find a technique that allowed for a temporary elimination of the uniqueness of each line in each drawing. From one point of view this is sublation, from another it is compression.

A bin lattice is placed over the drawings whose addresses are organized following a Hilbert curve. Now, local densities in the tangles can be meaningfully evaluated across the collection. After this cleansing ritual is complete, it is no longer necessary to talk about thighs or breasts or elbows. The clustering algorithm copy and pasted from Github takes over, and even though big data seems to like it, someone on the stackoverflow boards refers to it as a ‘garbage in garbage out’ algorithm. I like it because trying to understanding it conjures an image of a handful of stones being tossed into a still lake. The ripples converge as a collection of cells. Voronoi cells, Benard cells, at the heart of self-organization there is very clearly no self to be found and maintained, only the bleeding out of scalar values that momentarily slide into a dimensional array. Just some feature vectors looking for an object. But for these drawings it will have to suffice, it is already more than enough for the robot to get to work.

C.T.

“Cheyney Thompson has made the technology, production, and distribution of painting the subject of his work for over a decade. Thompson employs rational structures, technological processes, and generative devices as part of ‘thinking through problems that organize themselves around the terms of painting’. With such a rigorous approach to the medium, he has produced visually engaging yet exacting work that addresses varieties of abstraction including pictorial, economic, and technological. The status of painting within competing technological modes of image production and the medium’s historical and technical conditions have been central concerns in much of Thompson’s recent work. As a technology, painting is both outmoded within the technics of the production and circulation of images, yet also able to continuously incorporate and internalize other technical modes of production. Thompson’s paintings readily engage the image, as mediated by precisely such a series of technologies – from perspective and photography to the cinematic apparatus and the digital artifact. [...]”

Excerpt from: João Ribas, in Metric Pedestal Cabengo Landlord Récit, MIT List Visual Arts Center, Cambridge 2013

Toolpaths for Bellona is the sixth solo exhibition by Cheyney Thompson at Galerie Buchholz. Cheyney Thompson (born 1975 in Baton Rouge) lives and works in New York.