Diego Perrone

07 Mar - 27 Apr 2013

DIEGO PERRONE

Scultura che non sia conchiglia non canta

7 March - 27 April 2013

Casey Kaplan is pleased to announce Scultura che non sia conchiglia non canta, an exhibition of new work by Diego Perrone (b. 1970, Asti). Perrone’s work utilizes a vocabulary of repeated references including ears, horns and bells that result in various shapes and new forms. Despite these reiterations, his works do not coalesce into a singular narrative, but rather emphasize an internal logic that operates in a poetic, almost mythical manner. Drawing from provincial and traditional histories, as well as the varied landscape of 20th century avant-garde movements (Futurism, Art Nouveau, and Arte Povera) the works are strongly rooted in process. His objects, drawings, and videos reveal themselves through a study of the operational aspects of their own creation, favoring a state of non finito that provides a window into their making and creates a layered sense of time.

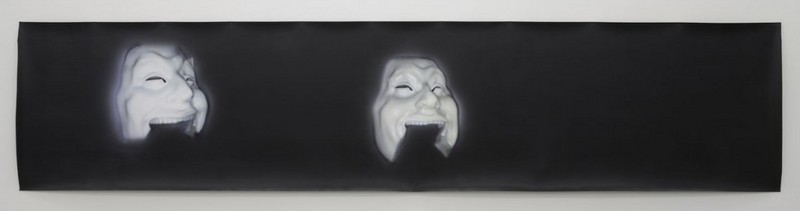

For his third exhibition with the gallery, Perrone presents two new bodies of work, both revolving around the appropriation of specific elements from sculptural and architectonic traditions. A series of airbrush paintings on PVC mark the beginning of an investigation into the sculpture of Adolfo Wildt (1868 – 1931, Milan), an Italian sculptor from the early 20th century noted for his Gothic influences. Little known, Wildt represents an important moment in Italian art, not only for his experimentation with the grotesque and symbolic, but also for his influence as a teacher to artists such as Lucio Fontana and Fausto Melotti, among others.

Sheets of PVC line the walls of all three gallery spaces, each depicting Wildt’s Maschera dell’Idiota (Idiot’s mask), c. 1910. Obsessive in both their rendering and their repetition, Perrone’s paintings are based from photographs taken of the mask in its vitrine at Il Vittoriale in Gardone Riviera, Italy, the former home of poet Gabriele D’Annunzio. Faithful to his own low-resolution photographs, Perrone’s paintings include the flash of his camera and the reflection of lights as he moved around the sculpture. Lit from below, the mask with its grotesque and exaggerated expression has a menacing gaze reminiscent of early horror and expressionist cinema. The mask becomes a laughing satyr, following the viewer throughout the gallery space. Verging on becoming 3-dimensional, it fluctuates from painting to sculpture as the nose appears to protrude from the PVC, and then fades into a flat, black expanse, leaving one with a haunting afterimage.

Occupying the second gallery is another kind of afterimage, the colossal shell of a mussel produced in resin and reaching over 10 feet in length. While the mussel has its place in the history of conceptual art in the work of Marcel Broodthaers, here it more closely relates to the a territory announced by the exhibition’s title, a quote from Gio Ponti’s In Praise of Architecture that translates to “Sculpture that is not a shell does not sing.” The shell itself occupies a unique place in the history of architecture as it was frequently used as a plastic, decorative element from the Roman through the Baroque periods. Partially suspended, the shell inhabits on a more liminal space as if it has been removed from its original setting, while still offering the semblance of its protection of something unknown. Verging on the uncanny in its scale, it demands its own history but simultaneously denies a singular explanation. Instead, the sculpture announces itself as something of a much more fluid origin – as a ghost.

Scultura che non sia conchiglia non canta

7 March - 27 April 2013

Casey Kaplan is pleased to announce Scultura che non sia conchiglia non canta, an exhibition of new work by Diego Perrone (b. 1970, Asti). Perrone’s work utilizes a vocabulary of repeated references including ears, horns and bells that result in various shapes and new forms. Despite these reiterations, his works do not coalesce into a singular narrative, but rather emphasize an internal logic that operates in a poetic, almost mythical manner. Drawing from provincial and traditional histories, as well as the varied landscape of 20th century avant-garde movements (Futurism, Art Nouveau, and Arte Povera) the works are strongly rooted in process. His objects, drawings, and videos reveal themselves through a study of the operational aspects of their own creation, favoring a state of non finito that provides a window into their making and creates a layered sense of time.

For his third exhibition with the gallery, Perrone presents two new bodies of work, both revolving around the appropriation of specific elements from sculptural and architectonic traditions. A series of airbrush paintings on PVC mark the beginning of an investigation into the sculpture of Adolfo Wildt (1868 – 1931, Milan), an Italian sculptor from the early 20th century noted for his Gothic influences. Little known, Wildt represents an important moment in Italian art, not only for his experimentation with the grotesque and symbolic, but also for his influence as a teacher to artists such as Lucio Fontana and Fausto Melotti, among others.

Sheets of PVC line the walls of all three gallery spaces, each depicting Wildt’s Maschera dell’Idiota (Idiot’s mask), c. 1910. Obsessive in both their rendering and their repetition, Perrone’s paintings are based from photographs taken of the mask in its vitrine at Il Vittoriale in Gardone Riviera, Italy, the former home of poet Gabriele D’Annunzio. Faithful to his own low-resolution photographs, Perrone’s paintings include the flash of his camera and the reflection of lights as he moved around the sculpture. Lit from below, the mask with its grotesque and exaggerated expression has a menacing gaze reminiscent of early horror and expressionist cinema. The mask becomes a laughing satyr, following the viewer throughout the gallery space. Verging on becoming 3-dimensional, it fluctuates from painting to sculpture as the nose appears to protrude from the PVC, and then fades into a flat, black expanse, leaving one with a haunting afterimage.

Occupying the second gallery is another kind of afterimage, the colossal shell of a mussel produced in resin and reaching over 10 feet in length. While the mussel has its place in the history of conceptual art in the work of Marcel Broodthaers, here it more closely relates to the a territory announced by the exhibition’s title, a quote from Gio Ponti’s In Praise of Architecture that translates to “Sculpture that is not a shell does not sing.” The shell itself occupies a unique place in the history of architecture as it was frequently used as a plastic, decorative element from the Roman through the Baroque periods. Partially suspended, the shell inhabits on a more liminal space as if it has been removed from its original setting, while still offering the semblance of its protection of something unknown. Verging on the uncanny in its scale, it demands its own history but simultaneously denies a singular explanation. Instead, the sculpture announces itself as something of a much more fluid origin – as a ghost.