William Kentridge

29 Oct 2005 - 15 Jan 2006

WILLIAM KENTRIDGE

Black Box / Chambre Noire

In conceiving of a new art work as part of the Deutsche Bank and Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation’s commissioning program for the Deutsche Guggenheim, William Kentridge, a South African artist very much grounded in geographies and histories of place, took as a point of departure the commission’s originating site—broadly speaking, Germany. In addition to his body of work exploring the history of Africa and South Africa, Kentridge has also long exhibited an affinity to German art and culture, creating works inspired by or in response to German visual artists and literary figures.

Within this contextual framework, the artist began to explore the history of German colonialism in Africa through the lens of its colonialera cinema. The process was undertaken while Kentridge was preparing to direct a major production of Mozart’s opera The Magic Flute, creating highly allusive imagery for the set designs and projections using a stage maquette. That work on Mozart’s Enlightenment-themed opera would lead Kentridge to Black Box / Chambre Noire, which explores the darker implications of that era’s philosophical legacy, reflects the key process of reversal that so often takes center stage in the artist’s work.

In 1989 Kentridge began a series of hand-drawn, animated films that focus on apartheid- and post-apartheid-era South Africa’s through the lens of two fictive white characters who can be seen as his alter-egos: the pensive, cautious Felix Teitlebaum and the aggressive industrialist Soho Eckstein. These films launched the artist into international prominence, yet Kentridge had already established himself in South Africa with his work in a range of mediums, including theater, graphic and fine arts, and filmmaking.

Kentridge’s work reflects a deep engagement with issues of history and memory. Using vigorously reworked charcoal and pastel drawings as the primary basis for his films, he leaves traces of erasure and highly visible pentimenti to suggest the work’s process and the ineradicable presence of the past. Kentridge is also known for his collaborations with the Handspring Puppet Company, with whom he has crafted complex, multimedia performances combining puppets, animation, and live performance.

In theatrical productions and video sculptures, he has employed objects and their cast shadows, the puppet and the hand of the puppeteer, as well as his signature traces and erasures, to develop complex, multilayered works which call into question notions of agency.

Black Box / Chambre Noire consists of animated films, kinetic sculptural objects, drawings, and a mechanized theater in miniature. In the work, Kentridge considers the term “black box” in three senses: a “black box” theater, a “chambre noire” as it relates to photography, and the “black box” flight data recorder used to record information in an airline disaster.

Kentridge explores constructions of history and meaning, while examining the processes of grief, guilt, culpability, and expiation, and the shifting vantage points of political engagement and responsibilty. The development of visual technologies and the history of colonialism intersect in Black Box / Chambre Noire through Kentridge’s reflection on the history of the German colonial presence in Africa, in particular the 1904 German massacre of the Hereros in Southwest Africa (now Namibia).

Considered by some historians to be the first genocide of the twentieth century, the German massacre of the Hereros in Southwest Africa resulted in a near annihilation of the tribe. In 1885 Southwest Africa became a German protectorate. German settlers increasingly encroached upon and expropriated the land of the Hereros through fraudulent treaties and usurious practices, causing the Hereros to fall into ever-increasing circles of debt and resulting in the losses of their cattle and land. As the tribes’ frustration rose, Samuel Mahareru, the Herero chief, was pressured by his community to respond to the escalating injustices.

In 1904, he ordered his subchiefs to carry out a directed attack against the ruling Germans, giving explicit instructions to avoid killing women, children, missionaries, English settlers, Boers, and other tribes. Stunned by this development, the German Kaiser appointed General Lothar von Trotha, known for his ruthlessness in suppressing revolts in East Africa and China, to lead a counterstrike. To escape the ensuing massacre, many Hereros fled into the Omaheke desert in an attempt to reach safety. The extreme harshness of the climate led to thousands of deaths, adding to the already significant toll of those killed directly by the troops. Despite objections by Germans in the colony as well as at home to General von Trotha’s extreme measures, it wasn’t until 1905, after seventy-five percent of the Herero population was decimated, that the General was removed from command. South Africa took control of Namibia in 1914 and ruled by force until Namibia gained its independence in 1990.

This historical fact relates to William Kentridge’s South African identity, prompting him to question notions of agency and complicity, atonement and grief.

In engaging issues of trauma and its aftermath, Kentridge explores the Freudian concept of “Trauerarbeit,” or grief work, a labor which is ongoing, and which dovetails with the artist’s unrelenting and selfreflexive examination of the process of making meaning. In creating a work that reveals the motors of representation, Kentridge renders these means transparent, removing the veil of opacity behind which selective, subjective memories are crafted into grand narratives of history. The process-oriented, at times collaborative aspects of Kentridge’s work results in the complex and richly layered nature of Black Box / Chambre Noire. Kentridge created numerous drawings for the Black Box theater and animated film, composing drawings onto and out of numerous period texts, including materials the artist came across in trips to Namibia and its national archive.*

Through the artist’s unique filmic process, these drawings are in turn integrated into the Black Box / Chambre Noire film, combined with the artist’s own footage of Namibia, archival photographs and excerpts from German colonial-era film. Additionally, the music that Kentridge, together with Philip Miller, the composer of the Black Box / Chambre Noire soundtrack, encountered in Namibia has been deftly woven into the piece.**

Black Box / Chambre Noire explores the difficulties inherent in representing historical trauma and in reconstructing events and people through the lens of a particular time, place, and politics, whether through the apparatus of cinema or pseudo-scientific constructions of “race.” Once again, there is no standing “outside” in Kentridge’s work. Black Box / Chambre Noire implicates us in our belief and disbelief, in our wonder and cool knowingness, in darkness and in light. In Kentridge’s metaphorical exploration of the Black Box as theater, camera obscura, and flight-data recorder, flexibility, fixity, and the future come into play in an exploration of the past. Resisting closure, the work problematizes simplistic constructions of history using binaries of past and present, victim and victimizer, spectacle and spectator.

Black Box / Chambre Noire explores the difficulties inherent in representing historical trauma and in reconstructing events and people through the lens of a particular time, place, and politics, whether through the apparatus of cinema or pseudo-scientific constructions of “race.” Once again, there is no standing “outside” in Kentridge’s work. Black Box / Chambre Noire implicates us in our belief and disbelief, in our wonder and cool knowingness, in darkness and in light. In Kentridge’s metaphorical exploration of the Black Box as theater, camera obscura, and flight-data recorder, flexibility, fixity, and the future come into play in an exploration of the past. Resisting closure, the work problematizes simplistic constructions of history using binaries of past and present, victim and victimizer, spectacle and spectator.

*Kentridge’s drawings combine charcoal, colored pastel, and colored pencil on paper as well as found texts including the following: lists of mines and shares; Italian ledger book circa 1920; student’s handwritten lecture notes on German law, 1911; vintage Johannesburg street map circa 1940; indexes from French scientific notes; French textbook, La merveille de la science, circa 1868; 1910 edition of the British text Mrs. Beeton’s Book of Household Management; text on the relative value of gold coins; Universale Tariffa, circa 1833; Chamber’s Encyclopedia of 1950; Introduction to Telephony textbook, 1934; Cyclopedia of Drawing, 1924; Photocopies of advertisements featured in the German journal Simplicissimus; share accounts of gold mines; Baedecker travel guide to Italy, circa 1900; Georg Hartmann’s map of German South West Africa, 1904; private correspondence from German South West Africa circa 1911; photocopy of General von Trotha’s 1904 order against the Hereros from the Namibian National Archive; Index and Gazetteer of the World; Stieler’s Handatlas No. 59, 1906; Statistics of Revenues and Debts of the Component States.

**The soundtrack for Black Box / Chambre Noire includes the following musical elements: Herero lament; Herero praise song; traditional Namibian bow music; Philip Miller’s original musical compositions.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s opera Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute): Sarastro’s Aria, „In diesen heil’gen Hallen“ from the 1937 recording of Sir Thomas Beecham conducting the Berlin Philharmonic; fragments from the Queen of the Night’s Aria “Der Hölle Rache”; Pamina’s Aria „Ach ich fühl’s, es ist verschwunden“; exchange between Papageno + Monastatos; „Marsch der Priester“ (“March of the Priests”) with Alfred Makgalemele singing.

William Kentridge, born 1955, lives and works in Johannesburg, South Africa.

© William Kentridge

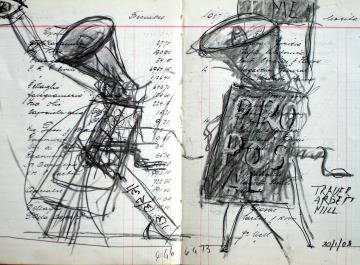

Untitled (drawing for Black Box/Chambre Noire), 2005

Photo: John Hodgkiss

Black Box / Chambre Noire

In conceiving of a new art work as part of the Deutsche Bank and Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation’s commissioning program for the Deutsche Guggenheim, William Kentridge, a South African artist very much grounded in geographies and histories of place, took as a point of departure the commission’s originating site—broadly speaking, Germany. In addition to his body of work exploring the history of Africa and South Africa, Kentridge has also long exhibited an affinity to German art and culture, creating works inspired by or in response to German visual artists and literary figures.

Within this contextual framework, the artist began to explore the history of German colonialism in Africa through the lens of its colonialera cinema. The process was undertaken while Kentridge was preparing to direct a major production of Mozart’s opera The Magic Flute, creating highly allusive imagery for the set designs and projections using a stage maquette. That work on Mozart’s Enlightenment-themed opera would lead Kentridge to Black Box / Chambre Noire, which explores the darker implications of that era’s philosophical legacy, reflects the key process of reversal that so often takes center stage in the artist’s work.

In 1989 Kentridge began a series of hand-drawn, animated films that focus on apartheid- and post-apartheid-era South Africa’s through the lens of two fictive white characters who can be seen as his alter-egos: the pensive, cautious Felix Teitlebaum and the aggressive industrialist Soho Eckstein. These films launched the artist into international prominence, yet Kentridge had already established himself in South Africa with his work in a range of mediums, including theater, graphic and fine arts, and filmmaking.

Kentridge’s work reflects a deep engagement with issues of history and memory. Using vigorously reworked charcoal and pastel drawings as the primary basis for his films, he leaves traces of erasure and highly visible pentimenti to suggest the work’s process and the ineradicable presence of the past. Kentridge is also known for his collaborations with the Handspring Puppet Company, with whom he has crafted complex, multimedia performances combining puppets, animation, and live performance.

In theatrical productions and video sculptures, he has employed objects and their cast shadows, the puppet and the hand of the puppeteer, as well as his signature traces and erasures, to develop complex, multilayered works which call into question notions of agency.

Black Box / Chambre Noire consists of animated films, kinetic sculptural objects, drawings, and a mechanized theater in miniature. In the work, Kentridge considers the term “black box” in three senses: a “black box” theater, a “chambre noire” as it relates to photography, and the “black box” flight data recorder used to record information in an airline disaster.

Kentridge explores constructions of history and meaning, while examining the processes of grief, guilt, culpability, and expiation, and the shifting vantage points of political engagement and responsibilty. The development of visual technologies and the history of colonialism intersect in Black Box / Chambre Noire through Kentridge’s reflection on the history of the German colonial presence in Africa, in particular the 1904 German massacre of the Hereros in Southwest Africa (now Namibia).

Considered by some historians to be the first genocide of the twentieth century, the German massacre of the Hereros in Southwest Africa resulted in a near annihilation of the tribe. In 1885 Southwest Africa became a German protectorate. German settlers increasingly encroached upon and expropriated the land of the Hereros through fraudulent treaties and usurious practices, causing the Hereros to fall into ever-increasing circles of debt and resulting in the losses of their cattle and land. As the tribes’ frustration rose, Samuel Mahareru, the Herero chief, was pressured by his community to respond to the escalating injustices.

In 1904, he ordered his subchiefs to carry out a directed attack against the ruling Germans, giving explicit instructions to avoid killing women, children, missionaries, English settlers, Boers, and other tribes. Stunned by this development, the German Kaiser appointed General Lothar von Trotha, known for his ruthlessness in suppressing revolts in East Africa and China, to lead a counterstrike. To escape the ensuing massacre, many Hereros fled into the Omaheke desert in an attempt to reach safety. The extreme harshness of the climate led to thousands of deaths, adding to the already significant toll of those killed directly by the troops. Despite objections by Germans in the colony as well as at home to General von Trotha’s extreme measures, it wasn’t until 1905, after seventy-five percent of the Herero population was decimated, that the General was removed from command. South Africa took control of Namibia in 1914 and ruled by force until Namibia gained its independence in 1990.

This historical fact relates to William Kentridge’s South African identity, prompting him to question notions of agency and complicity, atonement and grief.

In engaging issues of trauma and its aftermath, Kentridge explores the Freudian concept of “Trauerarbeit,” or grief work, a labor which is ongoing, and which dovetails with the artist’s unrelenting and selfreflexive examination of the process of making meaning. In creating a work that reveals the motors of representation, Kentridge renders these means transparent, removing the veil of opacity behind which selective, subjective memories are crafted into grand narratives of history. The process-oriented, at times collaborative aspects of Kentridge’s work results in the complex and richly layered nature of Black Box / Chambre Noire. Kentridge created numerous drawings for the Black Box theater and animated film, composing drawings onto and out of numerous period texts, including materials the artist came across in trips to Namibia and its national archive.*

Through the artist’s unique filmic process, these drawings are in turn integrated into the Black Box / Chambre Noire film, combined with the artist’s own footage of Namibia, archival photographs and excerpts from German colonial-era film. Additionally, the music that Kentridge, together with Philip Miller, the composer of the Black Box / Chambre Noire soundtrack, encountered in Namibia has been deftly woven into the piece.**

Black Box / Chambre Noire explores the difficulties inherent in representing historical trauma and in reconstructing events and people through the lens of a particular time, place, and politics, whether through the apparatus of cinema or pseudo-scientific constructions of “race.” Once again, there is no standing “outside” in Kentridge’s work. Black Box / Chambre Noire implicates us in our belief and disbelief, in our wonder and cool knowingness, in darkness and in light. In Kentridge’s metaphorical exploration of the Black Box as theater, camera obscura, and flight-data recorder, flexibility, fixity, and the future come into play in an exploration of the past. Resisting closure, the work problematizes simplistic constructions of history using binaries of past and present, victim and victimizer, spectacle and spectator.

Black Box / Chambre Noire explores the difficulties inherent in representing historical trauma and in reconstructing events and people through the lens of a particular time, place, and politics, whether through the apparatus of cinema or pseudo-scientific constructions of “race.” Once again, there is no standing “outside” in Kentridge’s work. Black Box / Chambre Noire implicates us in our belief and disbelief, in our wonder and cool knowingness, in darkness and in light. In Kentridge’s metaphorical exploration of the Black Box as theater, camera obscura, and flight-data recorder, flexibility, fixity, and the future come into play in an exploration of the past. Resisting closure, the work problematizes simplistic constructions of history using binaries of past and present, victim and victimizer, spectacle and spectator.

*Kentridge’s drawings combine charcoal, colored pastel, and colored pencil on paper as well as found texts including the following: lists of mines and shares; Italian ledger book circa 1920; student’s handwritten lecture notes on German law, 1911; vintage Johannesburg street map circa 1940; indexes from French scientific notes; French textbook, La merveille de la science, circa 1868; 1910 edition of the British text Mrs. Beeton’s Book of Household Management; text on the relative value of gold coins; Universale Tariffa, circa 1833; Chamber’s Encyclopedia of 1950; Introduction to Telephony textbook, 1934; Cyclopedia of Drawing, 1924; Photocopies of advertisements featured in the German journal Simplicissimus; share accounts of gold mines; Baedecker travel guide to Italy, circa 1900; Georg Hartmann’s map of German South West Africa, 1904; private correspondence from German South West Africa circa 1911; photocopy of General von Trotha’s 1904 order against the Hereros from the Namibian National Archive; Index and Gazetteer of the World; Stieler’s Handatlas No. 59, 1906; Statistics of Revenues and Debts of the Component States.

**The soundtrack for Black Box / Chambre Noire includes the following musical elements: Herero lament; Herero praise song; traditional Namibian bow music; Philip Miller’s original musical compositions.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s opera Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute): Sarastro’s Aria, „In diesen heil’gen Hallen“ from the 1937 recording of Sir Thomas Beecham conducting the Berlin Philharmonic; fragments from the Queen of the Night’s Aria “Der Hölle Rache”; Pamina’s Aria „Ach ich fühl’s, es ist verschwunden“; exchange between Papageno + Monastatos; „Marsch der Priester“ (“March of the Priests”) with Alfred Makgalemele singing.

William Kentridge, born 1955, lives and works in Johannesburg, South Africa.

© William Kentridge

Untitled (drawing for Black Box/Chambre Noire), 2005

Photo: John Hodgkiss