Jana Euler

10 Dec 2015 - 03 Feb 2016

JANA EULER

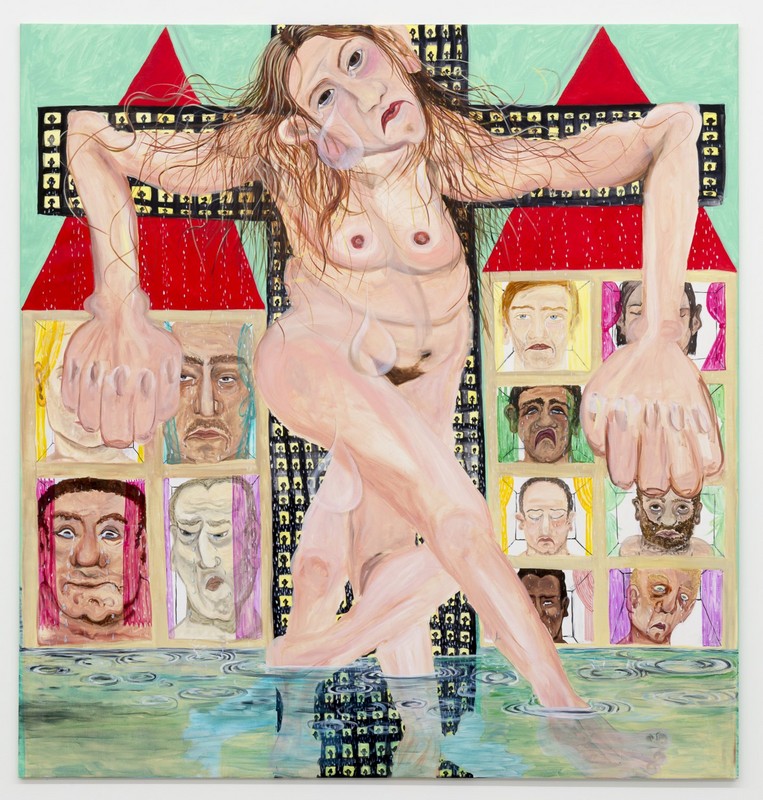

Female Jesus crying in public

10 December 2016 - 3 February 2016

The painting that gives the show its title, Female Jesus crying in public (2015) features a female figure hanging on a cross made from skyscrapers. In the buildings’ windows one can discern men’s faces that, in spite of their spatial isolation from one another, all cry as a group. Jesus self-consciously adopts the role here of a male artist whose task is to achieve great things and to die, in public and in pain, in order to attain immortality. Euler points out that this version of stoic self-righteousness – usually buttressed by a fan group that sees its task as helping to carry out this mandate – is usually a position reserved in the art world for men. Women suffer in private. Not this female Jesus, however, who Euler initially depicted giving the middle finger. Though she later painted over it, Euler deliberately left traces of this gesture visible. She achieves a simple reversal here: The female figure takes on a role with masculine connotations (the figure’s four legs speak to a mobile corporeality, or perhaps indicate that this figure is actually made up of many bodies), while men are allowed to cry in private. Nonetheless, everyone grieves together.

As if to underscore this, there is another painting in the exhibition depicting a Jesus-like flute player (Untitled, 2015) who, enclosed in a thin silver frame, steps forward toward the sunset that shines upon him while playing his song. Compared to Female Jesus crying in public, this work is rendered in a very slow and painterly manner. This underlines again the simplicity of Euler’s concept – if one imagines a woman in this painting instead of the male figure then very different associations would arise.

The works in this show were painted at different speeds and with different levels of exactitude in their rendering. They all have different formats. Even though the paintings were all made in the last year as a unified body of work, they appear more loosely connected to one another than works that Euler has previously grouped in her exhibitions. There are connections here to the artist’s shows that are running concurrently to the exhibition at Galerie Neu, for instance in Frankfurt at the Portikus. The work Frankfurt (2015), for example, a painting that one can connect either to Euler’s provenance, or to the world of finance that is also settled in the city. The skyline here is presented upside down, on its head. Again, a simple reversal. This might remind one of Baselitz, who once said in an interview that women’s paintings are less expensive because women are worse painters than men. The notion of changes in perspective also informs the work In the perspective of the screwed 2 (2015). In the center of the painting one sees a screw in reverse perspective, as it were. The large swirl around the screw’s head appears to move outward toward the surface because the screw’s threading is depicted as if it were being seen from the back. As the screw recedes, the threading moves towards the viewer in a continuous stretch. Instead of diminishing in perspective towards a vanishing point, the screw thus occupies the entire painting. It’s unclear whether this interpretation will immediately reveal itself to the viewer. It could also appear like a screw flying in a tunnel, or one falling into a shallow pond. Although the painting is built around a clear idea, the image lends itself to multiple readings.

The two paintings of airplanes, Cockpit and Cabin (both 2015) both show exactly what their titles announce. In one work we see empty rows of airplane seats and in the other one we see part of an airplane cockpit whose complicated equipment immediately jumps out at the eye. The insistent, fact-like depiction of emptiness here reminds one of how immobile these airplane chairs are, in which one must sit either for a short, or a long while in a contingently assembled constellation. There are some who are flown and others who know how to fly. The paintings point out that one must accept a certain position, one of being pilot-controlled, driven, in order to move from A to B. The series Universe 1, 2 & 3 (2015) also exudes a similar fascination with facticity. The three paintings, each airbrushed with black ink, feature lonesome hearts that swirl around the universe in isolation. Hearts are somewhat of an icon in Euler’s work, appearing in her show at the Kunsthalle Zürich and also at Portikus. They are faces made of genitals, that touch themselves, but which only have one meaning: to exist, to be direct, to look at you. These paintings make no claim to fulfill a greater communicative act. They make that which is considered in the world to be most individual (like loneliness, sexuality, desire, simplicity, the gaze) into something generally perceptible.

In this world of perspective switches, facticity and multiple references, the painting Jeune Fille, ein Selbstportrait (2015) stands out. The self-portrait captures the moment in which the artist received her diving permit at age twelve, a moment first was captured in the photograph attached to the permit. The facial expression points to an almost overwhelming “stream of selfconfidence.” In transferring the image to such a large format, however, small vulnerabilities, injuries perhaps, naturally emerge because the expression changes, the colors are no longer correct, and the whole thing can become kitch. The painting seems to lie in a personal tradition, in which Euler represents things directly drawn from her personal history, as in her last show at Galerie Neu, where she exhibited Badewanne I & II (2013), works representing the bathtub in her parents’ house. This further clarifies Euler’s position as an artist who does not try to conceal the subjective elements present in her work, but instead freely works with both direct and hermetic subjects simultaneously, and brings these disparate elements into dialogue.

The scope of her preoccupation with the self clearly emerges in the juxtaposition of Jeune Fille, ein Selbstportrait and before words (2015), a work in which an emoticon designed by Euler appears enthroned upon three very familiar emoticons. Its “emoticon staff” appears like a totem pole that can entrance viewers into participating in occult prayer. This figure at the top seems to sleep with itself, that is, it is preoccupied with itself. It has climbed to the top, overreaching itself figuratively and literally in the painting. The others must subject themselves to the ironies of messages sent by other people, while the top emoticon’s lack of immediate familiarity renders him more independent. It is not simply a filler.

As if to break with the paintings’ exaggerated signifiers, or to provide them with the potential to somehow change over time, the exhibition is replete with three moveable rows of airplane seats that one can move in front of the paintings to sit and gaze at the works from different angles and for long periods of time.

The almost naïve, quasi objective observation of the energies that ‘speak’ from paintings, as well as a very personal set of meanings (while never promising authenticity) and an interest in the construction, invention and slippage between thoughts provide the parameters of Euler’s pictorial world. The representation of self (re)presentation engenders a layer of latent legibility that jumps from Euler’s works to the self (re)presentation of the viewer.

Melanie Ohnemus

Female Jesus crying in public

10 December 2016 - 3 February 2016

The painting that gives the show its title, Female Jesus crying in public (2015) features a female figure hanging on a cross made from skyscrapers. In the buildings’ windows one can discern men’s faces that, in spite of their spatial isolation from one another, all cry as a group. Jesus self-consciously adopts the role here of a male artist whose task is to achieve great things and to die, in public and in pain, in order to attain immortality. Euler points out that this version of stoic self-righteousness – usually buttressed by a fan group that sees its task as helping to carry out this mandate – is usually a position reserved in the art world for men. Women suffer in private. Not this female Jesus, however, who Euler initially depicted giving the middle finger. Though she later painted over it, Euler deliberately left traces of this gesture visible. She achieves a simple reversal here: The female figure takes on a role with masculine connotations (the figure’s four legs speak to a mobile corporeality, or perhaps indicate that this figure is actually made up of many bodies), while men are allowed to cry in private. Nonetheless, everyone grieves together.

As if to underscore this, there is another painting in the exhibition depicting a Jesus-like flute player (Untitled, 2015) who, enclosed in a thin silver frame, steps forward toward the sunset that shines upon him while playing his song. Compared to Female Jesus crying in public, this work is rendered in a very slow and painterly manner. This underlines again the simplicity of Euler’s concept – if one imagines a woman in this painting instead of the male figure then very different associations would arise.

The works in this show were painted at different speeds and with different levels of exactitude in their rendering. They all have different formats. Even though the paintings were all made in the last year as a unified body of work, they appear more loosely connected to one another than works that Euler has previously grouped in her exhibitions. There are connections here to the artist’s shows that are running concurrently to the exhibition at Galerie Neu, for instance in Frankfurt at the Portikus. The work Frankfurt (2015), for example, a painting that one can connect either to Euler’s provenance, or to the world of finance that is also settled in the city. The skyline here is presented upside down, on its head. Again, a simple reversal. This might remind one of Baselitz, who once said in an interview that women’s paintings are less expensive because women are worse painters than men. The notion of changes in perspective also informs the work In the perspective of the screwed 2 (2015). In the center of the painting one sees a screw in reverse perspective, as it were. The large swirl around the screw’s head appears to move outward toward the surface because the screw’s threading is depicted as if it were being seen from the back. As the screw recedes, the threading moves towards the viewer in a continuous stretch. Instead of diminishing in perspective towards a vanishing point, the screw thus occupies the entire painting. It’s unclear whether this interpretation will immediately reveal itself to the viewer. It could also appear like a screw flying in a tunnel, or one falling into a shallow pond. Although the painting is built around a clear idea, the image lends itself to multiple readings.

The two paintings of airplanes, Cockpit and Cabin (both 2015) both show exactly what their titles announce. In one work we see empty rows of airplane seats and in the other one we see part of an airplane cockpit whose complicated equipment immediately jumps out at the eye. The insistent, fact-like depiction of emptiness here reminds one of how immobile these airplane chairs are, in which one must sit either for a short, or a long while in a contingently assembled constellation. There are some who are flown and others who know how to fly. The paintings point out that one must accept a certain position, one of being pilot-controlled, driven, in order to move from A to B. The series Universe 1, 2 & 3 (2015) also exudes a similar fascination with facticity. The three paintings, each airbrushed with black ink, feature lonesome hearts that swirl around the universe in isolation. Hearts are somewhat of an icon in Euler’s work, appearing in her show at the Kunsthalle Zürich and also at Portikus. They are faces made of genitals, that touch themselves, but which only have one meaning: to exist, to be direct, to look at you. These paintings make no claim to fulfill a greater communicative act. They make that which is considered in the world to be most individual (like loneliness, sexuality, desire, simplicity, the gaze) into something generally perceptible.

In this world of perspective switches, facticity and multiple references, the painting Jeune Fille, ein Selbstportrait (2015) stands out. The self-portrait captures the moment in which the artist received her diving permit at age twelve, a moment first was captured in the photograph attached to the permit. The facial expression points to an almost overwhelming “stream of selfconfidence.” In transferring the image to such a large format, however, small vulnerabilities, injuries perhaps, naturally emerge because the expression changes, the colors are no longer correct, and the whole thing can become kitch. The painting seems to lie in a personal tradition, in which Euler represents things directly drawn from her personal history, as in her last show at Galerie Neu, where she exhibited Badewanne I & II (2013), works representing the bathtub in her parents’ house. This further clarifies Euler’s position as an artist who does not try to conceal the subjective elements present in her work, but instead freely works with both direct and hermetic subjects simultaneously, and brings these disparate elements into dialogue.

The scope of her preoccupation with the self clearly emerges in the juxtaposition of Jeune Fille, ein Selbstportrait and before words (2015), a work in which an emoticon designed by Euler appears enthroned upon three very familiar emoticons. Its “emoticon staff” appears like a totem pole that can entrance viewers into participating in occult prayer. This figure at the top seems to sleep with itself, that is, it is preoccupied with itself. It has climbed to the top, overreaching itself figuratively and literally in the painting. The others must subject themselves to the ironies of messages sent by other people, while the top emoticon’s lack of immediate familiarity renders him more independent. It is not simply a filler.

As if to break with the paintings’ exaggerated signifiers, or to provide them with the potential to somehow change over time, the exhibition is replete with three moveable rows of airplane seats that one can move in front of the paintings to sit and gaze at the works from different angles and for long periods of time.

The almost naïve, quasi objective observation of the energies that ‘speak’ from paintings, as well as a very personal set of meanings (while never promising authenticity) and an interest in the construction, invention and slippage between thoughts provide the parameters of Euler’s pictorial world. The representation of self (re)presentation engenders a layer of latent legibility that jumps from Euler’s works to the self (re)presentation of the viewer.

Melanie Ohnemus