Kholin and Sapgir

Manuscripts

20 May - 13 Aug 2017

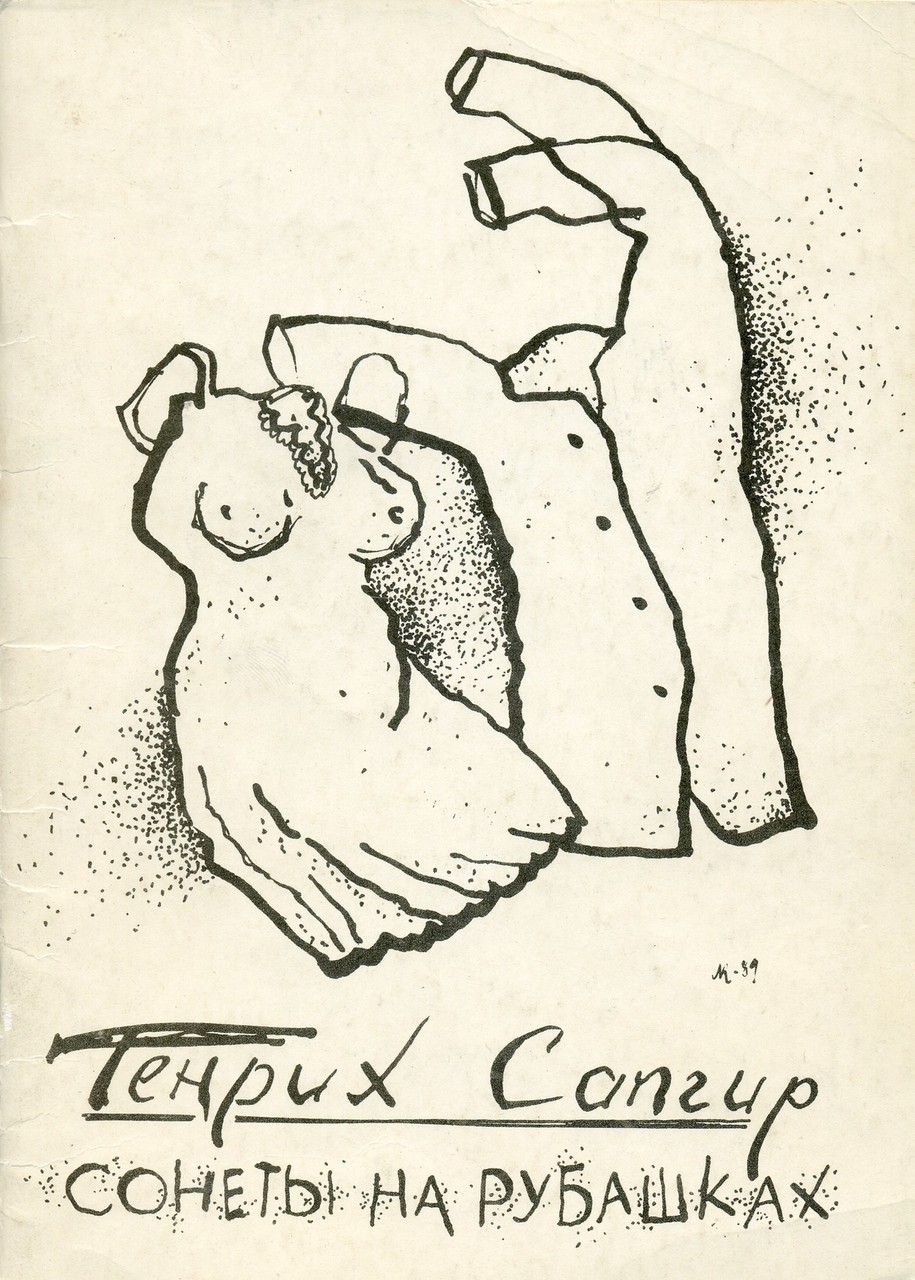

Cover of Sonnets on Shirts by Genrikh Sapgir. Artwork by Lev Kropivnitsky. Published by Prometey, Moscow State V. I. Lenin Pedagogical Institute. 1989

Garage Library, Moscow

Garage Library, Moscow

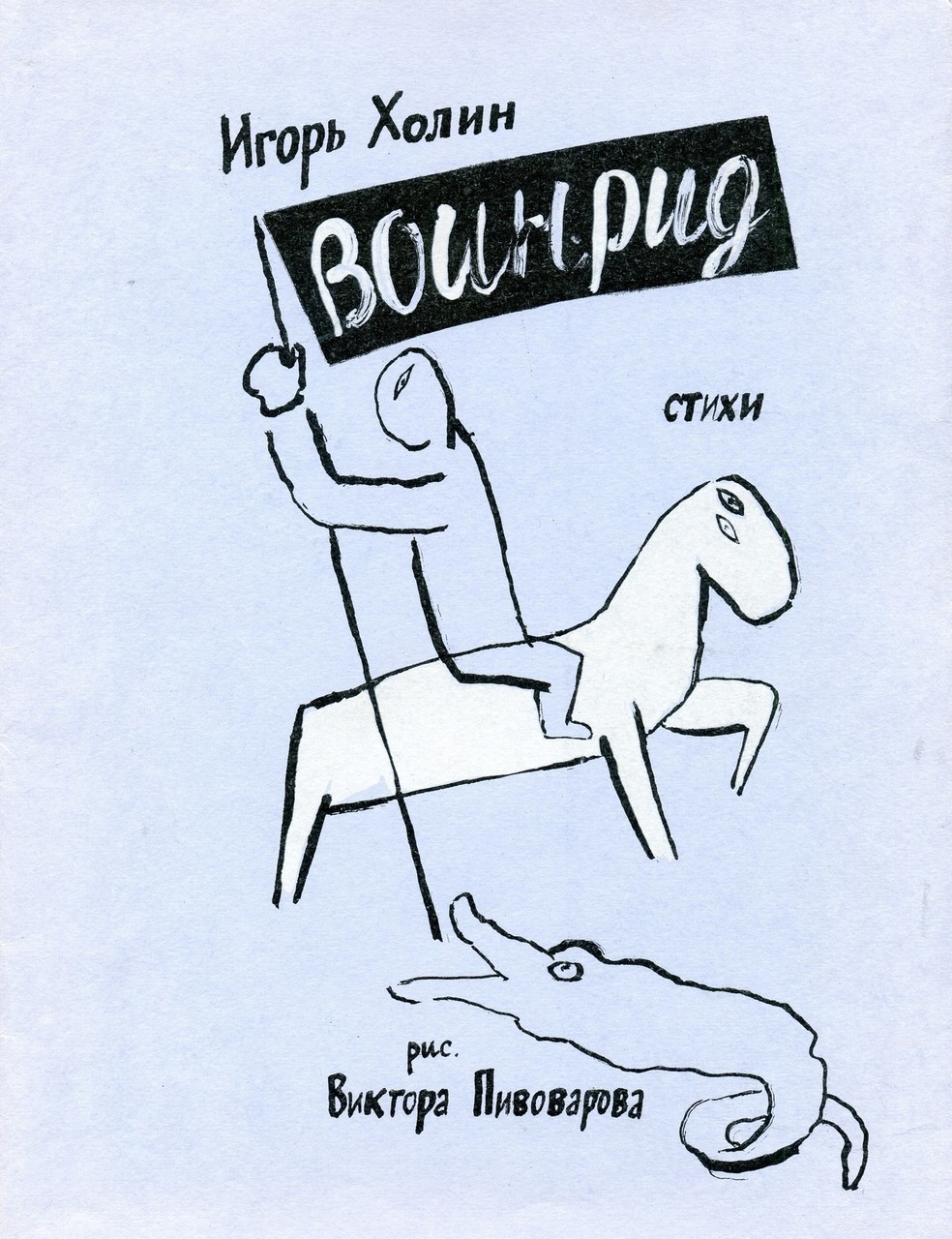

Cover of Voinrid by Igor Kholin, with illustrations by Viktor Pivovarov. Published by S. Nitochkin. No 433/537. 1993

Garage Library, Moscow

Garage Library, Moscow

Genrikh Sapgir and Igor Kholin at an exhibition at the Beekeeping Pavilion, VDNKh, Moscow. 1975

Igor Palmin Collection

Garage Archive Collection, Moscow

Igor Palmin Collection

Garage Archive Collection, Moscow

KHOLIN AND SAPGIR

Manuscripts

20 May - 13 August 2017

This summer, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art presents an exhibition of documents relating to the poetry of Igor Kholin (1920–1999) and Genrikh Sapgir (1928–1999), offering fresh insight into the work of two pioneers of Soviet nonconformist literature. Their names are often encountered together: in literary analysis, in publications on Russian contemporary art, and on children’s book shelves.

Kholin and Sapgir met in 1952 and became close allies. Both were members of the first postwar unofficial community of artists and poets, known as the Lianozovo group, and pupils of its leader, artist Evgeny Kropivnitsky. They worked alongside some of the key names in Russian postwar art, including Oskar Rabin, Lydia Masterkova, and Vladimir Nemukhin. Bohemians of the 1960s and 1970s, their avant-garde poetry was unpublishable until the advent of perestroika. They were heroes of the literary underground, pioneers of samizdat, and featured in the first issue of the samizdat poetry journal Sintaksis, published by Alexander Ginsburg in 1959. Both combined an innovative style of writing with a strong commitment to truth, and a genuine interest in the life of ordinary people. They fused expressionism and realism, with an acute sense of the tragedy of the everyday and the poetics of the absurd. Their funny and moving “barracks poetry” quickly became part of Soviet folklore, often quoted by people who had never read the original texts. Kholin and Sapgir led a double life typical of nonconformist writers and artists of the post-Stalin era: showing their work only to a small audience of friends and admirers, they took odd jobs to make a living. Kholin worked as a waiter at the Metropol Restaurant, while Sapgir was an engineer at the Sculpture Studio of the USSR Arts Fund. Both became famous as authors of children’s poetry, which was read by generations of Soviet kids. Sapgir also wrote scripts for a number of classic animated films.

Featuring recent acquisitions from Garage Archive Collection, at the heart of the exhibition are manuscripts and samizdat publications donated by artist Viktor Pivovarov, some signed by the authors and many including previously unpublished poems. These are exhibited alongside Pivovarov’s illustrations for Kholin and Sapgir’s unpublished works, and his sketches for the album Kholin and Sapgir Triumphant. The exhibition also features typewritten texts from the archives of Leonid Talochkin and Igor Makarevich, as well as photographic portraits of the poets by one of the chroniclers of the Moscow underground scene of the 1960s and 1970s, Igor Palmin. To provide a broader picture of the Soviet nonconformist literary scene and the lives of the two poets, the exhibition includes newspaper articles and journal clippings from Garage Archive Collection and photographs from the poets’ family archives, as well as recordings of Kholin and Sapgir made in the late 1980s by German researchers Sabine Haensgen and Georg Witte, which were featured in the multimedia collection Lianozovo School (1992).

Garage Library presents its collection of books featuring works by Kholin and Sapgir, including collections of poetry and prose published in the 1990s and 2000s; Kholin and Sapgir’s children’s books with illustrations by leading artists such as Viktor Pivovarov, Erik Bulatov, and Oleg Vassiliev; and animated films from the 1960s and 1970s scripted by Sapgir.

The exhibition is organized by Sasha Obukhova, curator of Garage Archive Collection, with the assistance of assistant curator Ekaterina Lazareva and archivist Antonina Trubitsina.

Igor Kholin

Igor Kholin was born in Moscow in 1920. In 1927, he was put in an orphanage. After running away, he lived on the streets until he was sent to a children’s work camp in the early 1930s. In 1934, he started work at a glass factory in Kryukov, near Moscow, and then became homeless again. In 1936, he was admitted to a military school in Kharkov. From 1937 to 1940, he was assistant engineer at a power plant in Novorossiysk. In 1940 and 1941, he served in the army’s music corps and later studied at a military school in Gomel. He saw active service in World War II from 1941 to 1945, and was wounded several times. In 1949, he was sentenced to two years in a labor camp for an administrative offense. During his time at the camp Kholin met poet and artist Evgeny Kropivnitsky and his family, who lived in the neighboring village of Dolgoprudny. He soon became part of the Lianozovo group. Although he started writing poetry in 1949, it was only after meeting Kropivnitsky that Kholin developed his own poetic style and wrote the cycle of “barracks poems” for which he is best known. In the late 1950s, he started writing poems for children and was published officially. His nonconformist works were published only in samizdat, or outside the Soviet Union. In the 1970s, he stopped writing for children and switched to prose, going on to write short stories in the 1980s and 1990s. Kholin died in Moscow in 1999.

Genrikh Sapgir

Genrikh Sapgir was born in Biysk (Altai krai) in 1928. His father was a Moscow engineer who later returned to the capital. In 1944, Sapgir began attending classes at the House of Pioneers and met the poet and artist Evgeny Kropivnitsky, the leader of what later came to be known as Lianozovo circle. Sapgir became part of the group after completing his army service and soon, influenced by Kropivnitsky, switched from traditional to experimental poetry. In the Soviet Union he was well-known as an author of children’s poetry and a translator, but his experimental works were published only in samizdat and outside of the Soviet Union. In 1979, his poetry was featured in the samizdat journal Metropol, of which twelve copies were initially published, which would later be reissued by Ardis Publishing in the USA. In 1988, Sapgir joined the Moscow Union of Writers and, in 1995, became a member of PEN International. He died in Moscow in 1999.

Manuscripts

20 May - 13 August 2017

This summer, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art presents an exhibition of documents relating to the poetry of Igor Kholin (1920–1999) and Genrikh Sapgir (1928–1999), offering fresh insight into the work of two pioneers of Soviet nonconformist literature. Their names are often encountered together: in literary analysis, in publications on Russian contemporary art, and on children’s book shelves.

Kholin and Sapgir met in 1952 and became close allies. Both were members of the first postwar unofficial community of artists and poets, known as the Lianozovo group, and pupils of its leader, artist Evgeny Kropivnitsky. They worked alongside some of the key names in Russian postwar art, including Oskar Rabin, Lydia Masterkova, and Vladimir Nemukhin. Bohemians of the 1960s and 1970s, their avant-garde poetry was unpublishable until the advent of perestroika. They were heroes of the literary underground, pioneers of samizdat, and featured in the first issue of the samizdat poetry journal Sintaksis, published by Alexander Ginsburg in 1959. Both combined an innovative style of writing with a strong commitment to truth, and a genuine interest in the life of ordinary people. They fused expressionism and realism, with an acute sense of the tragedy of the everyday and the poetics of the absurd. Their funny and moving “barracks poetry” quickly became part of Soviet folklore, often quoted by people who had never read the original texts. Kholin and Sapgir led a double life typical of nonconformist writers and artists of the post-Stalin era: showing their work only to a small audience of friends and admirers, they took odd jobs to make a living. Kholin worked as a waiter at the Metropol Restaurant, while Sapgir was an engineer at the Sculpture Studio of the USSR Arts Fund. Both became famous as authors of children’s poetry, which was read by generations of Soviet kids. Sapgir also wrote scripts for a number of classic animated films.

Featuring recent acquisitions from Garage Archive Collection, at the heart of the exhibition are manuscripts and samizdat publications donated by artist Viktor Pivovarov, some signed by the authors and many including previously unpublished poems. These are exhibited alongside Pivovarov’s illustrations for Kholin and Sapgir’s unpublished works, and his sketches for the album Kholin and Sapgir Triumphant. The exhibition also features typewritten texts from the archives of Leonid Talochkin and Igor Makarevich, as well as photographic portraits of the poets by one of the chroniclers of the Moscow underground scene of the 1960s and 1970s, Igor Palmin. To provide a broader picture of the Soviet nonconformist literary scene and the lives of the two poets, the exhibition includes newspaper articles and journal clippings from Garage Archive Collection and photographs from the poets’ family archives, as well as recordings of Kholin and Sapgir made in the late 1980s by German researchers Sabine Haensgen and Georg Witte, which were featured in the multimedia collection Lianozovo School (1992).

Garage Library presents its collection of books featuring works by Kholin and Sapgir, including collections of poetry and prose published in the 1990s and 2000s; Kholin and Sapgir’s children’s books with illustrations by leading artists such as Viktor Pivovarov, Erik Bulatov, and Oleg Vassiliev; and animated films from the 1960s and 1970s scripted by Sapgir.

The exhibition is organized by Sasha Obukhova, curator of Garage Archive Collection, with the assistance of assistant curator Ekaterina Lazareva and archivist Antonina Trubitsina.

Igor Kholin

Igor Kholin was born in Moscow in 1920. In 1927, he was put in an orphanage. After running away, he lived on the streets until he was sent to a children’s work camp in the early 1930s. In 1934, he started work at a glass factory in Kryukov, near Moscow, and then became homeless again. In 1936, he was admitted to a military school in Kharkov. From 1937 to 1940, he was assistant engineer at a power plant in Novorossiysk. In 1940 and 1941, he served in the army’s music corps and later studied at a military school in Gomel. He saw active service in World War II from 1941 to 1945, and was wounded several times. In 1949, he was sentenced to two years in a labor camp for an administrative offense. During his time at the camp Kholin met poet and artist Evgeny Kropivnitsky and his family, who lived in the neighboring village of Dolgoprudny. He soon became part of the Lianozovo group. Although he started writing poetry in 1949, it was only after meeting Kropivnitsky that Kholin developed his own poetic style and wrote the cycle of “barracks poems” for which he is best known. In the late 1950s, he started writing poems for children and was published officially. His nonconformist works were published only in samizdat, or outside the Soviet Union. In the 1970s, he stopped writing for children and switched to prose, going on to write short stories in the 1980s and 1990s. Kholin died in Moscow in 1999.

Genrikh Sapgir

Genrikh Sapgir was born in Biysk (Altai krai) in 1928. His father was a Moscow engineer who later returned to the capital. In 1944, Sapgir began attending classes at the House of Pioneers and met the poet and artist Evgeny Kropivnitsky, the leader of what later came to be known as Lianozovo circle. Sapgir became part of the group after completing his army service and soon, influenced by Kropivnitsky, switched from traditional to experimental poetry. In the Soviet Union he was well-known as an author of children’s poetry and a translator, but his experimental works were published only in samizdat and outside of the Soviet Union. In 1979, his poetry was featured in the samizdat journal Metropol, of which twelve copies were initially published, which would later be reissued by Ardis Publishing in the USA. In 1988, Sapgir joined the Moscow Union of Writers and, in 1995, became a member of PEN International. He died in Moscow in 1999.