Erwin Thorn

05 Oct - 09 Nov 2008

ERWIN THORN

In engaging with the discourses of the conceptual avant-garde in the 1960s, Erwin Thorn developed an independent artistic position all his own. “Occasional affinities can be made out to the visual strategies of a Hans Bischoffshausen, as well as orms parallel to the work of the artists in the Düsseldorf ZERO group around Heinz ack, Otto Piene, and Günther Uecker. At the same time, he is interested in the work and ttitude of Karl Prantl,” as Roland Schöny summarizes.

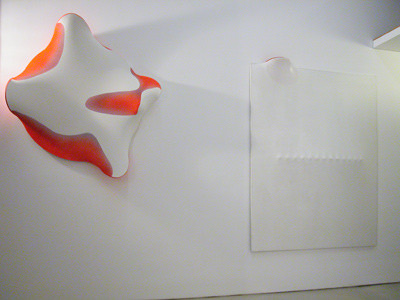

In large spatial installations, sculptural images or image-like sculptures, collages nd fine paper works, he explores emancipative perspectives with the concept of anguage and reversal when it comes to the question of traditional relationships nd he visual communication of events. Rhythm and waves—also reminiscent of ound waves, thus making clear the audio aspect of language—are an important spect of Thorn’s conceptual work. “His visual language can be described as a isual, linguistic system, in which the coordinates consist of elevations and epressions,” and consciously sets himself apart not only “from the individual estural work of abstract expressionism, art autre, and the Informel” (Schöny), but lso distances himself from the esoteric interests of European art movements. His urn away from the pathos-laden formulas of the 1950s and 1960s is exhibited in a reductionistically formal order,” as Thorn himself describes.2 Here, “nothing is not othing, but a breathing surface” that with an architectural character explores onstructs in spatial terms and seems systematized by concave and convex distortions. Beyond any mannerisms, he intervenes in the flat surfaces, anipulating them, executing his formal principles in different work groups. A hange in the beholder’s perspective makes clear the complex play with structures ith shadow and light, omissions and distortions, visible forms, and those first evealed by the movement of the beholder, which Thorn conceives as symbolic.

With irony and humor, Thorn breaks the semiological plane over and over. The erm Ohrwaschel, an invented word (the English equivalent might be “ear waxel”) ome of the objects humorously makes clear the linkage of elevations and epressions as forms, visual associations to the tone-setting rhythms and language. e conceives “the visual medium as a language, and language does ndeed transport content” (Thorn).

In so doing, “earnestness and sensuality are by no means mutually exclusive, but he condition for one another” (Schöny). All of Thorn’s formal studies are ommitted to this primacy, as is clearly shown in the biomorphic spatial installation on der Wiege ins Boot [From the Cradle to the Boat]. Inserted into the corner of a oom, a vertical reminiscent of a joint with bones seems to coagulate at the argins, reminiscent of “very delicate drops,” as Alfred Schmeller in 1960 wrote on a hrorn sculpture, by and in so doing, the “plausible result of a critical reflection about the reek column as a symbol of power” (Schöny).

In engaging with the discourses of the conceptual avant-garde in the 1960s, Erwin Thorn developed an independent artistic position all his own. “Occasional affinities can be made out to the visual strategies of a Hans Bischoffshausen, as well as orms parallel to the work of the artists in the Düsseldorf ZERO group around Heinz ack, Otto Piene, and Günther Uecker. At the same time, he is interested in the work and ttitude of Karl Prantl,” as Roland Schöny summarizes.

In large spatial installations, sculptural images or image-like sculptures, collages nd fine paper works, he explores emancipative perspectives with the concept of anguage and reversal when it comes to the question of traditional relationships nd he visual communication of events. Rhythm and waves—also reminiscent of ound waves, thus making clear the audio aspect of language—are an important spect of Thorn’s conceptual work. “His visual language can be described as a isual, linguistic system, in which the coordinates consist of elevations and epressions,” and consciously sets himself apart not only “from the individual estural work of abstract expressionism, art autre, and the Informel” (Schöny), but lso distances himself from the esoteric interests of European art movements. His urn away from the pathos-laden formulas of the 1950s and 1960s is exhibited in a reductionistically formal order,” as Thorn himself describes.2 Here, “nothing is not othing, but a breathing surface” that with an architectural character explores onstructs in spatial terms and seems systematized by concave and convex distortions. Beyond any mannerisms, he intervenes in the flat surfaces, anipulating them, executing his formal principles in different work groups. A hange in the beholder’s perspective makes clear the complex play with structures ith shadow and light, omissions and distortions, visible forms, and those first evealed by the movement of the beholder, which Thorn conceives as symbolic.

With irony and humor, Thorn breaks the semiological plane over and over. The erm Ohrwaschel, an invented word (the English equivalent might be “ear waxel”) ome of the objects humorously makes clear the linkage of elevations and epressions as forms, visual associations to the tone-setting rhythms and language. e conceives “the visual medium as a language, and language does ndeed transport content” (Thorn).

In so doing, “earnestness and sensuality are by no means mutually exclusive, but he condition for one another” (Schöny). All of Thorn’s formal studies are ommitted to this primacy, as is clearly shown in the biomorphic spatial installation on der Wiege ins Boot [From the Cradle to the Boat]. Inserted into the corner of a oom, a vertical reminiscent of a joint with bones seems to coagulate at the argins, reminiscent of “very delicate drops,” as Alfred Schmeller in 1960 wrote on a hrorn sculpture, by and in so doing, the “plausible result of a critical reflection about the reek column as a symbol of power” (Schöny).