David Goldblatt

07 Oct - 06 Nov 2010

© David Goldblatt

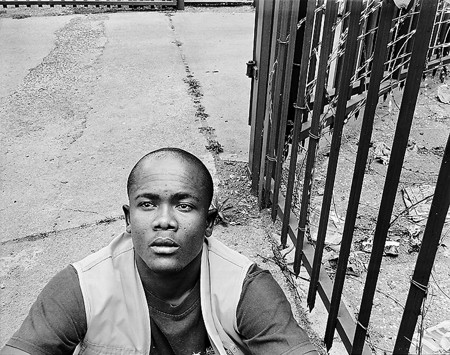

Trevor Mabuela, born in Alexandra Township, Johannesburg, was fourteen years old in 1995, ‘when we got our freedom and were free to go to the suburbs where we weren’t allowed before. We told ourselves that we were going to the parks and swimming pools – we didn’t have pools here – to play, but that’s when we started doing crime’. They went to malls and stole sweets and marbles, ‘those stupid things kids like to play with...We found boys our age playing with bicycles. We grabbed them. We took their bikes and brought them to the location. We became a group of bikers... We started smoking when we started earning money from crime. Then we could afford beers and try to impress the ladies in the taverns... From cigarettes we did zoll, then drugs, then crack. That’s when we became corrupt. We left school. Every time we didn’t have money we did crime.’ Trevor was nineteen when his mother gave him money to get a driver’s license. ‘I took that money and ate it on drink and clothes, things like that.’ He couldn’t go home without the money or the license, so he called on a couple of friends to help him raise funds and they attempted to hijack a woman reversing out of a factory in nearby Kew. His friend screamed at her to open the door and get out. She refused. His friend fired his pistol but didn’t hit her. She drove off and met some police who gave chase. It was 5pm. People were pouring out of factories. His friends disappeared into the busy streets. Trevor was caught. Sent to jail for twenty years for attempted murder, his sentence was reduced to ten years on appeal and he served five. His friends, never caught, have started families and businesses. Aged 28, Trevor hopes to complete his schooling and get a job. (4_A0541), 2010

Silver gelatin photograph on fibre-based paper

Trevor Mabuela, born in Alexandra Township, Johannesburg, was fourteen years old in 1995, ‘when we got our freedom and were free to go to the suburbs where we weren’t allowed before. We told ourselves that we were going to the parks and swimming pools – we didn’t have pools here – to play, but that’s when we started doing crime’. They went to malls and stole sweets and marbles, ‘those stupid things kids like to play with...We found boys our age playing with bicycles. We grabbed them. We took their bikes and brought them to the location. We became a group of bikers... We started smoking when we started earning money from crime. Then we could afford beers and try to impress the ladies in the taverns... From cigarettes we did zoll, then drugs, then crack. That’s when we became corrupt. We left school. Every time we didn’t have money we did crime.’ Trevor was nineteen when his mother gave him money to get a driver’s license. ‘I took that money and ate it on drink and clothes, things like that.’ He couldn’t go home without the money or the license, so he called on a couple of friends to help him raise funds and they attempted to hijack a woman reversing out of a factory in nearby Kew. His friend screamed at her to open the door and get out. She refused. His friend fired his pistol but didn’t hit her. She drove off and met some police who gave chase. It was 5pm. People were pouring out of factories. His friends disappeared into the busy streets. Trevor was caught. Sent to jail for twenty years for attempted murder, his sentence was reduced to ten years on appeal and he served five. His friends, never caught, have started families and businesses. Aged 28, Trevor hopes to complete his schooling and get a job. (4_A0541), 2010

Silver gelatin photograph on fibre-based paper

DAVID GOLDBLATT

"TJ: Some Things Old, Some Things New and Some Much The Same"

07 October - 06 November 2010

Johannesburg Gallery

Photographer David Goldblatt brings together old and new photographs of Johannesburg in a solo exhibition at Goodman Gallery titled TJ: Some things old, some things new and some much the same. TJ – an obsolete acronym stemming from the South African pre-computerised system of motorcar registrations – stood for “Transvaal, Johannesburg”. These letters, Goldblatt explains, “implied a certain loyalty”. While some of the photographs to be on show at the Goodman Gallery were taken in what Goldblatt refers to as the “time of TJ”, the title refers to the notion that particular aspects of the city have changed very little since that era and in some cases, worsened. The exhibition ultimately elucidates on these particular aspects of the sprawling city of Johannesburg, which both infuriate and astound the photographer.

“One of the most damaging things that apartheid did to us,” Goldblatt says, “was that it denied us the experience of each other’s lives. Apartheid has succeeded all too well. It might have failed in its fundamental purpose of ruling the country for the next thousand years in that fashion, but it succeeded in dividing us very deeply and it will take a long time to overcome that.” This deep-rooted division is further exacerbated by a continuing social and urban fragmentation. While TJ includes old black and white photographs from an earlier era, new works explore the intricacies of crime, housing and poverty in Joburg.

Much of Goldblatt’s frustration lies in the city’s remarkable oversights, greed and lack of planning. “When we came out of the apartheid regime the Johannesburg municipality was split up and the Gauteng province became responsible for planning in the north-west and they just didn’t plan,” explains Goldblatt. “The result was that to a large degree property developers were at liberty to develop pretty well as they liked.” At the same time exorbitant amounts are spent on stadia and events such as the Miss World competition, while certain areas, such as Diepsloot, remain in dire need of basic facilities such as school libraries and storm water drainage systems. The urban sprawl that the city has become, as well as its often-desperate and baffling conditions, is revealed through aerial shots of the indiscriminately structured northern suburbs and townships, photographs of Zimbabwean refugees sleeping in a congested Methodist church and of the ruins of an amusement park in the foreground of Soccer City – a conflicting icon of growth and prodigality with a budget overrun of R800 million.

In another recent series, Goldblatt has focussed on ex-offenders, inviting them to revisit the scenes of the crimes that led to their incarceration and be photographed there. “I don’t believe that many of them are inherently evil,” says Goldblatt. “They came to their crime for a whole lot of other reasons.” In the 20 plus ex-offenders who he has met, Goldblatt – while admitting that this is only a small sample – has picked up on various factors and patterns that seem to contribute to their criminal behaviour such as domestic dysfunctionality (many, he found, grew up without fathers), and a dire education system. “We have failed a very large number of young black people in this country in regard to their education,” he says. “We had Bantu education under apartheid, and that was a crime against humanity, because it educated deliberately to under-educate. But the education of millions of young black people in post-apartheid has been almost as bad... their ability to mobilise upwards and out of the ranks of the poor is very limited. They’re at a tremendous disadvantage from the start.”

As always Goldblatt’s photographic style is unaffected and direct, reflecting art critic Ken Johnson’s observation that the “effect of Mr. Goldblatt’s understated, antisensational photographs and the spare words that accompany them is cumulative. They build into an infectiously mournful beauty. Even in pictures that seem almost nondescript... Mr. Goldblatt’s compositions have a classical elegance and a reticence that speaks volumes.”

David Goldblatt was born in 1930 in Randfontein, South Africa and since the early 1960s he has devoted all of his time to photography. In 1989 Goldblatt founded the Market Photography Workshop in Johannesburg, with, he explains “the object of teaching visual literacy and photographic skills to young people, with particular emphasis on those disadvantaged by apartheid”. In 1998 he was the first South African to be given a one-person exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York. Goldblatt received an Honorary Doctorate in Fine Arts at the University of Cape Town in 2001. The same year a retrospective exhibition of his work, David Goldblatt Fifty-One Years, began a tour of galleries and museums in New York, Barcelona, Rotterdam, Lisbon, Oxford, Brussels, Munich and Johannesburg. He was one of the few South African artists to exhibit at Documenta 11 in Kassel, Germany in 2002. He recently held solo exhibitions at the Jewish Museum (which travels to the South African Jewish Museum in October this year) and the New Museum, both in New York and is currently exhibiting alongside photographers such as Walker Evans and Bruce Nauman in The Original Copy: Photography of Sculpture, 1839 to Today at MoMA. Goldblatt’s photographs are in the collections of the South African National Gallery, Cape Town; the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris; the Victoria and Albert Museum, London; and MoMA. He has published several books of his work. Goldblatt is the recipient of the 2006 Hasselblad award, the 2009 Henri Cartier-Bresson Award and was recently announced the 2010 Lucie Award Lifetime Achievement Honoree.

"TJ: Some Things Old, Some Things New and Some Much The Same"

07 October - 06 November 2010

Johannesburg Gallery

Photographer David Goldblatt brings together old and new photographs of Johannesburg in a solo exhibition at Goodman Gallery titled TJ: Some things old, some things new and some much the same. TJ – an obsolete acronym stemming from the South African pre-computerised system of motorcar registrations – stood for “Transvaal, Johannesburg”. These letters, Goldblatt explains, “implied a certain loyalty”. While some of the photographs to be on show at the Goodman Gallery were taken in what Goldblatt refers to as the “time of TJ”, the title refers to the notion that particular aspects of the city have changed very little since that era and in some cases, worsened. The exhibition ultimately elucidates on these particular aspects of the sprawling city of Johannesburg, which both infuriate and astound the photographer.

“One of the most damaging things that apartheid did to us,” Goldblatt says, “was that it denied us the experience of each other’s lives. Apartheid has succeeded all too well. It might have failed in its fundamental purpose of ruling the country for the next thousand years in that fashion, but it succeeded in dividing us very deeply and it will take a long time to overcome that.” This deep-rooted division is further exacerbated by a continuing social and urban fragmentation. While TJ includes old black and white photographs from an earlier era, new works explore the intricacies of crime, housing and poverty in Joburg.

Much of Goldblatt’s frustration lies in the city’s remarkable oversights, greed and lack of planning. “When we came out of the apartheid regime the Johannesburg municipality was split up and the Gauteng province became responsible for planning in the north-west and they just didn’t plan,” explains Goldblatt. “The result was that to a large degree property developers were at liberty to develop pretty well as they liked.” At the same time exorbitant amounts are spent on stadia and events such as the Miss World competition, while certain areas, such as Diepsloot, remain in dire need of basic facilities such as school libraries and storm water drainage systems. The urban sprawl that the city has become, as well as its often-desperate and baffling conditions, is revealed through aerial shots of the indiscriminately structured northern suburbs and townships, photographs of Zimbabwean refugees sleeping in a congested Methodist church and of the ruins of an amusement park in the foreground of Soccer City – a conflicting icon of growth and prodigality with a budget overrun of R800 million.

In another recent series, Goldblatt has focussed on ex-offenders, inviting them to revisit the scenes of the crimes that led to their incarceration and be photographed there. “I don’t believe that many of them are inherently evil,” says Goldblatt. “They came to their crime for a whole lot of other reasons.” In the 20 plus ex-offenders who he has met, Goldblatt – while admitting that this is only a small sample – has picked up on various factors and patterns that seem to contribute to their criminal behaviour such as domestic dysfunctionality (many, he found, grew up without fathers), and a dire education system. “We have failed a very large number of young black people in this country in regard to their education,” he says. “We had Bantu education under apartheid, and that was a crime against humanity, because it educated deliberately to under-educate. But the education of millions of young black people in post-apartheid has been almost as bad... their ability to mobilise upwards and out of the ranks of the poor is very limited. They’re at a tremendous disadvantage from the start.”

As always Goldblatt’s photographic style is unaffected and direct, reflecting art critic Ken Johnson’s observation that the “effect of Mr. Goldblatt’s understated, antisensational photographs and the spare words that accompany them is cumulative. They build into an infectiously mournful beauty. Even in pictures that seem almost nondescript... Mr. Goldblatt’s compositions have a classical elegance and a reticence that speaks volumes.”

David Goldblatt was born in 1930 in Randfontein, South Africa and since the early 1960s he has devoted all of his time to photography. In 1989 Goldblatt founded the Market Photography Workshop in Johannesburg, with, he explains “the object of teaching visual literacy and photographic skills to young people, with particular emphasis on those disadvantaged by apartheid”. In 1998 he was the first South African to be given a one-person exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York. Goldblatt received an Honorary Doctorate in Fine Arts at the University of Cape Town in 2001. The same year a retrospective exhibition of his work, David Goldblatt Fifty-One Years, began a tour of galleries and museums in New York, Barcelona, Rotterdam, Lisbon, Oxford, Brussels, Munich and Johannesburg. He was one of the few South African artists to exhibit at Documenta 11 in Kassel, Germany in 2002. He recently held solo exhibitions at the Jewish Museum (which travels to the South African Jewish Museum in October this year) and the New Museum, both in New York and is currently exhibiting alongside photographers such as Walker Evans and Bruce Nauman in The Original Copy: Photography of Sculpture, 1839 to Today at MoMA. Goldblatt’s photographs are in the collections of the South African National Gallery, Cape Town; the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris; the Victoria and Albert Museum, London; and MoMA. He has published several books of his work. Goldblatt is the recipient of the 2006 Hasselblad award, the 2009 Henri Cartier-Bresson Award and was recently announced the 2010 Lucie Award Lifetime Achievement Honoree.