Ezra Johnson

12 Jan - 06 May 2007

Hammer Projects

Ezra Johnson

January 12 - May 6, 2007

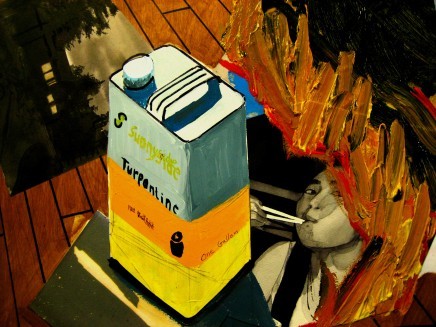

Ezra Johnson's new animated low-tech digital film, What Visions Burn (2006), uses lushly colored paintings and collaged figures to tell the story of a pair of art thieves in New York City. The animation is a laborious process, as Johnson paints and repaints the surface of his canvases to create each frame of the film, which uses visual elements and sound effects to narrate the scenario. Johnson's amusing depictions of the art world's many characters and his poetic representations of the city tell a story both romantic and unexpected.

About the Exhibition

by Jan Tumlir

The insistent call for a “pure cinema” built on the model of “pure painting” comes close to supplying experimental art film with a point of origin and a destiny, as well as a sound historical logic to connect them, although the question of just what constitutes purity at either end has yielded numerous conflicting replies. For many, it is the attention that has been paid to the irreducible attributes of painting in the most medium-specific sense that is to be followed. In the case of film, therefore, a whole other order of specificity would have to be found. Then there are those—like Oskar Fischinger, Len Lye, and Harry Smith—who have applied the model of painting more literally, appropriating the technical means of painterly abstraction for filmic use, either by animating the painterly process one frame at a time with a rostrum camera setup or else by painting directly on celluloid. This second, more straightforward take on the matter can be traced all the way back to the work of the Italian Futurists Arnaldo Ginna and Bruno Corra, who are known to have hand-painted strips of raw film and projected the results as early as 1910—shortly after the emergence of cinema as such. It is within a Futurist manifesto from 1916 entitled “The Futurist Cinema” that the point is made unequivocally that “the cinema, being essentially visual, must above all fulfill the evolution of painting, detach itself from reality, from photography, from the graceful and solemn. It must become anti-graceful, deforming, impressionistic, synthetic, dynamic, free.”

This same string of adjectives could be used to describe Ezra Johnson’s painting-film What Visions Burn, which is surprising considering the very different cultural context that he inhabits. It would seem that the once-fierce opposition between the cultural margins and mainstream has largely been quelled, leading to a general relaxation of tensions in all matters of aesthetic “engagement.” The assignment of ideological values to formal terms such as “anti-graceful, deforming, impressionistic, etc.,” a once very nearly automatic operation, must now undergo continual reevaluation.

The assumption that a vote for the painterly is a vote against “reality,” which in turn is unambiguously associated with realism and representation, no longer holds. Johnson resumes the discussion initiated by the Futurists from a resolutely postmodern perspective. The designation is meaningful, for if the influence of painting on cinema was formerly understood as “deformative” in the strictly modernist sense of prioritizing the individual, abstracting imagination over the exercise of objective perception, then we may now begin to consider the reverse equation of the cinema’s influence on painting. What succeeds the modern is effectively what precedes it, what the modern repressed and, by the same token, transformed: the image. Alongside such contemporary figures as William Kentridge, Kara Walker, and Paul Chan, all artists known for their work in animation, Johnson has openly aligned himself with a figurative tradition. But this is a figuration strained through a filmic template that has itself been strained through the template of painterly abstraction (and so forth and so on).

Delving into the impossibly baroque knots and tangles of this relation is clearly at the crux of Johnson’s project. This is film both of and about painting, and it is painting both of and about film. The ambition that compelled the various avant-garde movements to animate painting—to make this static, plastic object move—is here taken up literally as process, and allegorically as narrative. Moreover, this is Hollywood narrative of the most conventional sort: What Visions Burn is essentially a “heist film,” or as Ed Ruscha describes all his narrative projects, a “caper,” one that concerns the theft of art from a museum.

Within the enfolding frame of this movement-painting, we witness a continual subdivision of our visual field into a series of ever smaller paintings that also move but in an entirely different manner. Cut out of their frames in the museum, transported from one locale to another, changing hands among the film’s coterie of shady figures, these “secondary” paintings enact the push and pull of influence and inspiration that every young artist experiences as a clichéd story line. Undergoing a mercury-like process of disintegration and reintegration, painting is sent, from the first moment, on the spiraling course of the mise-en-abyme. And much the same holds true for film, which undergoes such a delirious pile-on of realist tropes that we lose any sense of their referential link to a “real world” source.

During the first theft sequence (there are two), we are shown the museum’s scanning security cameras filming these “secondary” paintings just as the “primary” painting is itself being filmed. Later the same surveillance footage yields a cover photo for the New York Post, an image reproduced in the film first as a collage of photographic and painterly elements, and then in turn reproduced by a painter within the painting that is itself being reproduced, frame by frame, as that sequence of still, photographic images that ultimately make up this moving-image film. Interestingly, at such flashpoints of self-reflexivity, the quality of Johnson’s paintwork appears to coarsen, as though devolving. In the sequence cited above, the hand of the painter is rendered as an oversize, undifferentiated mitt with protruding brush, an overlaid cutout, brusquely jiggled about—even the animation technique takes a turn for the worse. Such decisions are entirely conscious, however, and paradoxically exacting; the erosion of the realist image via this unsteady, regressing line amounts to a scrupulous tracing of the borders of artistic self-knowledge.

Referential overload and the corruption of the image are linked in such instances, pointing toward what is certainly an endemic condition within our informational moment: (technological) memory gain entails (human) memory loss. Johnson’s museum thieves are of course emblematic contemporary artist-types. It is no accident that we first make their acquaintance in the course of a gallery opening, as they slip by a beer-drinking clique of bearded bohemians and then don their masks on the way to the museum. Also telling is the movement between these two contexts, these repositories of new and old art, which serves to illuminate the mulching process that is intrinsic not only to this but also to so much work currently being made.

What follows is a series of vignettes that all of us can recognize from previously viewed films about artists and films about thieves, even as their structure grows increasingly confused. Here again, Johnson reenacts the postmodern play between influence and inspiration as painterly push-pull, a process yielding a steady buildup of images and genre conventions. The point of this exercise is to throw us off the trail, to make us “lose the plot,” much as the characters within the film appear to have done—both the genre-specific plot of this “caper” and the art-historical plot that inheres to its painterly ground. It is entirely appropriate that this painting-film, which opens on a rooftop view of New York City, ends in the country, as a lone car winds its way through a snowy mountain road. Stolen paintings have been traded for cash, and a couple is on the run, pushing deeper into the white field that must now symbolize both informational excess (snow crash) and absence. As we transition between that first painting and the last—via a proliferating accumulation of intermediate citations, quotations, repetitions, and recyclings—both the artist and his audience are granted a fleeting glimpse of that new beginning pursued by just about every avant-garde movement of the last century. The calendar is set back to Year Zero as the “virginal” canvas begins once more to show through the cinematic veil.

Ezra Johnson was born in 1975 in Wenatchee, Washington, and lives in Brooklyn. He received a BFA in painting in 2000 from the California College of Arts and Crafts, San Francisco. In 2006 he completed an MFA in painting at Hunter College, New York. While at Hunter, Johnson participated in an exchange program with the Universität der Kunst in Berlin, where he studied painting under Daniel Richter. His work has been shown in exhibitions in New York at Nicole Klagsbrun Gallery, Tilton Gallery, and Artists Space, and in Los Angeles at Kantor/Feuer Gallery. He is currently a 2006–2007 Winter Fellow at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, Massachusetts. This is Johnson's first solo museum exhibition.

Ezra Johnson

January 12 - May 6, 2007

Ezra Johnson's new animated low-tech digital film, What Visions Burn (2006), uses lushly colored paintings and collaged figures to tell the story of a pair of art thieves in New York City. The animation is a laborious process, as Johnson paints and repaints the surface of his canvases to create each frame of the film, which uses visual elements and sound effects to narrate the scenario. Johnson's amusing depictions of the art world's many characters and his poetic representations of the city tell a story both romantic and unexpected.

About the Exhibition

by Jan Tumlir

The insistent call for a “pure cinema” built on the model of “pure painting” comes close to supplying experimental art film with a point of origin and a destiny, as well as a sound historical logic to connect them, although the question of just what constitutes purity at either end has yielded numerous conflicting replies. For many, it is the attention that has been paid to the irreducible attributes of painting in the most medium-specific sense that is to be followed. In the case of film, therefore, a whole other order of specificity would have to be found. Then there are those—like Oskar Fischinger, Len Lye, and Harry Smith—who have applied the model of painting more literally, appropriating the technical means of painterly abstraction for filmic use, either by animating the painterly process one frame at a time with a rostrum camera setup or else by painting directly on celluloid. This second, more straightforward take on the matter can be traced all the way back to the work of the Italian Futurists Arnaldo Ginna and Bruno Corra, who are known to have hand-painted strips of raw film and projected the results as early as 1910—shortly after the emergence of cinema as such. It is within a Futurist manifesto from 1916 entitled “The Futurist Cinema” that the point is made unequivocally that “the cinema, being essentially visual, must above all fulfill the evolution of painting, detach itself from reality, from photography, from the graceful and solemn. It must become anti-graceful, deforming, impressionistic, synthetic, dynamic, free.”

This same string of adjectives could be used to describe Ezra Johnson’s painting-film What Visions Burn, which is surprising considering the very different cultural context that he inhabits. It would seem that the once-fierce opposition between the cultural margins and mainstream has largely been quelled, leading to a general relaxation of tensions in all matters of aesthetic “engagement.” The assignment of ideological values to formal terms such as “anti-graceful, deforming, impressionistic, etc.,” a once very nearly automatic operation, must now undergo continual reevaluation.

The assumption that a vote for the painterly is a vote against “reality,” which in turn is unambiguously associated with realism and representation, no longer holds. Johnson resumes the discussion initiated by the Futurists from a resolutely postmodern perspective. The designation is meaningful, for if the influence of painting on cinema was formerly understood as “deformative” in the strictly modernist sense of prioritizing the individual, abstracting imagination over the exercise of objective perception, then we may now begin to consider the reverse equation of the cinema’s influence on painting. What succeeds the modern is effectively what precedes it, what the modern repressed and, by the same token, transformed: the image. Alongside such contemporary figures as William Kentridge, Kara Walker, and Paul Chan, all artists known for their work in animation, Johnson has openly aligned himself with a figurative tradition. But this is a figuration strained through a filmic template that has itself been strained through the template of painterly abstraction (and so forth and so on).

Delving into the impossibly baroque knots and tangles of this relation is clearly at the crux of Johnson’s project. This is film both of and about painting, and it is painting both of and about film. The ambition that compelled the various avant-garde movements to animate painting—to make this static, plastic object move—is here taken up literally as process, and allegorically as narrative. Moreover, this is Hollywood narrative of the most conventional sort: What Visions Burn is essentially a “heist film,” or as Ed Ruscha describes all his narrative projects, a “caper,” one that concerns the theft of art from a museum.

Within the enfolding frame of this movement-painting, we witness a continual subdivision of our visual field into a series of ever smaller paintings that also move but in an entirely different manner. Cut out of their frames in the museum, transported from one locale to another, changing hands among the film’s coterie of shady figures, these “secondary” paintings enact the push and pull of influence and inspiration that every young artist experiences as a clichéd story line. Undergoing a mercury-like process of disintegration and reintegration, painting is sent, from the first moment, on the spiraling course of the mise-en-abyme. And much the same holds true for film, which undergoes such a delirious pile-on of realist tropes that we lose any sense of their referential link to a “real world” source.

During the first theft sequence (there are two), we are shown the museum’s scanning security cameras filming these “secondary” paintings just as the “primary” painting is itself being filmed. Later the same surveillance footage yields a cover photo for the New York Post, an image reproduced in the film first as a collage of photographic and painterly elements, and then in turn reproduced by a painter within the painting that is itself being reproduced, frame by frame, as that sequence of still, photographic images that ultimately make up this moving-image film. Interestingly, at such flashpoints of self-reflexivity, the quality of Johnson’s paintwork appears to coarsen, as though devolving. In the sequence cited above, the hand of the painter is rendered as an oversize, undifferentiated mitt with protruding brush, an overlaid cutout, brusquely jiggled about—even the animation technique takes a turn for the worse. Such decisions are entirely conscious, however, and paradoxically exacting; the erosion of the realist image via this unsteady, regressing line amounts to a scrupulous tracing of the borders of artistic self-knowledge.

Referential overload and the corruption of the image are linked in such instances, pointing toward what is certainly an endemic condition within our informational moment: (technological) memory gain entails (human) memory loss. Johnson’s museum thieves are of course emblematic contemporary artist-types. It is no accident that we first make their acquaintance in the course of a gallery opening, as they slip by a beer-drinking clique of bearded bohemians and then don their masks on the way to the museum. Also telling is the movement between these two contexts, these repositories of new and old art, which serves to illuminate the mulching process that is intrinsic not only to this but also to so much work currently being made.

What follows is a series of vignettes that all of us can recognize from previously viewed films about artists and films about thieves, even as their structure grows increasingly confused. Here again, Johnson reenacts the postmodern play between influence and inspiration as painterly push-pull, a process yielding a steady buildup of images and genre conventions. The point of this exercise is to throw us off the trail, to make us “lose the plot,” much as the characters within the film appear to have done—both the genre-specific plot of this “caper” and the art-historical plot that inheres to its painterly ground. It is entirely appropriate that this painting-film, which opens on a rooftop view of New York City, ends in the country, as a lone car winds its way through a snowy mountain road. Stolen paintings have been traded for cash, and a couple is on the run, pushing deeper into the white field that must now symbolize both informational excess (snow crash) and absence. As we transition between that first painting and the last—via a proliferating accumulation of intermediate citations, quotations, repetitions, and recyclings—both the artist and his audience are granted a fleeting glimpse of that new beginning pursued by just about every avant-garde movement of the last century. The calendar is set back to Year Zero as the “virginal” canvas begins once more to show through the cinematic veil.

Ezra Johnson was born in 1975 in Wenatchee, Washington, and lives in Brooklyn. He received a BFA in painting in 2000 from the California College of Arts and Crafts, San Francisco. In 2006 he completed an MFA in painting at Hunter College, New York. While at Hunter, Johnson participated in an exchange program with the Universität der Kunst in Berlin, where he studied painting under Daniel Richter. His work has been shown in exhibitions in New York at Nicole Klagsbrun Gallery, Tilton Gallery, and Artists Space, and in Los Angeles at Kantor/Feuer Gallery. He is currently a 2006–2007 Winter Fellow at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, Massachusetts. This is Johnson's first solo museum exhibition.