White Light / White Heat

27 Feb - 28 Mar 2009

WHITE LIGHT / WHITE HEAT

27 February – 28 March 2009

Hauser & Wirth London, Old Bond Street

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, On Kawara, Yves Klein, Piero Manzoni, Joan Mitchell, Piet Mondrian, Blinky Palermo, Jackson Pollock and Robert Ryman

‘WHITE LIGHT / WHITE HEAT’ presents seminal works by some of the twentieth century’s most important artists. Considered as a group, the works in this exhibition articulate the transition from Romantic expressionism to cool literalism that occurred in the past century, a shift brought about by figuration’s evolution into abstraction and then by an eschewal of the image altogether in favour of the conceptual. These artists fundamentally influenced the course of art, combining radical innovation with wit and intelligence.

The earliest work on display is an important painting by Piet Mondrian — Beach with one Pier at Domburg (Dune), one of a series executed by the artist in 1909, each testing a different style across the same motif. Through heightened colours Mondrian sought to create an all-encompassing art, which he believed to be beyond the possibilities of traditional painting. These paintings occupy a key place within Mondrian’s trajectory, representing the very beginnings of his path to abstraction: ‘The first thing to change in my painting was colour. I forsook natural colour for pure colour.’

Search is considered to be the last painting Jackson Pollock made and featured in his exhibition at Sydney Janis, New York in 1955. According to the art historian Elizabeth Frank ‘his late paintings are some of his most inventive and assured works, paintings of marked freedom and individuality.... Search maps out an unexpected all over synthesis between the puddle shapes of the black paintings and the semi-enclosed angles and contours of his pre-1947 paintings.’

The controlled abandon of Pollock’s gestures are a precursor to, but hardly a preparation for, Joan Mitchell’s Mandres (1961 – 1962) where rhythm and vibrancy are displaced for seemingly primordial matter. Made at a difficult time in the artist’s life, this extraordinary painting’s dark amorphous mass of opacities bear every possible means of her hand’s making. Yet for all the furies that Mitchell unleashed on her canvas, its facture was highly considered: “The freedom in my work is controlled,” she said, “If I want to undertake the act of painting in full liberty, I want to know what my brush is about to do.”

In contrast, Yves Klein turned to the elements to make his Cosmogony (1961), allowing rain to corrode an image into his International Klein Blue. Through colour, Klein aimed to express a world beyond the material, explaining: ‘before the coloured surface one finds oneself directly before the matter of the soul’, whilst provocatively undermining the transcendence of his gestures through his decision to trademark his pigment.

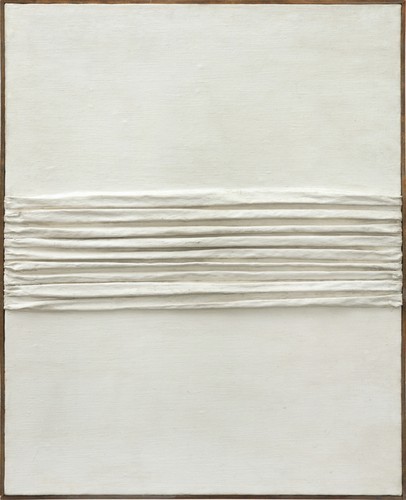

For Piero Manzoni the Sublime was to be looked for through the eradication of colour, yet even then his canvases remained impossibly impure. His Achrome (1959), literally ‘without colour’, is an early example of the series that made his reputation and which he continued until his early death. This series of all-white works began simply as folded sheets of cotton coated in kaolin (a fine clay used in porcelain), but increasingly introduced more artificial elements culminating in blond fibreglass curls. Manzoni allowed the material he used dictate his work. ‘It is not a question of shaping things, nor of articulating messages,’ he argued, ‘for are not fantasising, abstraction and self-expression empty fictions? There is nothing to be said: there is only to be, to live.’

Sharing with Manzoni a commitment to white, Robert Ryman narrowed his parameters further to mount a systematic investigation into the matter of paint. In Signet 20 (1965 – 1966) a two-inch wide brush has been charged with white oil paint and dragged from left to right across the canvas, with each swipe covering eight or so inches before having to be reloaded, forming fractured parallel lines that reveal the canvas below. Ryman often allowed his tools and paints to dictate a work’s title, and in this instance named the painting after the make and size of his chosen brush. Expunging any references in his works beyond his materials, Ryman made paint ‘the content of the paintings as well as the form.’

Matter and pigment are one in Blinky Palermo’s Blaue Scheibe und Stab (Blue Disc and Stick) (1968), whose powerful colour is inherent to the fabric tape that forms the outer surface of the forms. The composite sculpture is described by the art historian Benjamin H D Buchloh as one of his ‘absolute favourites ... an extraordinary conception in terms of material execution.’ Its blue bandaging arouses pathos whilst being fundamental to its construction. For the critic Jan Verwoert, in Palermo’s pieces ‘the sensation of seeing a sublime work was grounded in a bodily reality, the reality of which transformed the purity of the colour panels into something broken, intimate and almost tender.’

On Kawara’s Dec. 28, 1971 conveys little other than the existence of the artist when he painted it. His ‘Date Paintings’ are testaments to consciousness anchored, through the language and conventions of their script, to the country where they were made. Numbers and letters have been painstakingly hand drawn and painted to appear as impersonal as if made by a machine. For all their extreme reductivism and negation of expression, Kawara’s paintings possess an emotional force and metaphoric reach, eloquent precisely because of their uncompromising factuality.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s auratic Untitled (for New York) (1992) made from 42 light bulbs is one of 25 light string sculptures whose parenthetical titles point to memories or events that were important to him. In these, readily available hardware is used to conjure numerous associations: light as a symbol of spirituality and enlightenment, as a haven and source of warmth, and of life, as impermanent as each ephemeral bulb. Like memory, the meanings of each piece remain personal and mutable. There is no set instruction for how it should be installed, and in this way Gonzalez-Torres allows for continuous reinterpretation, democratically involving others in the making of the work. His aim was to move viewers to a ‘place of beauty, freedom, pleasure.’

27 February – 28 March 2009

Hauser & Wirth London, Old Bond Street

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, On Kawara, Yves Klein, Piero Manzoni, Joan Mitchell, Piet Mondrian, Blinky Palermo, Jackson Pollock and Robert Ryman

‘WHITE LIGHT / WHITE HEAT’ presents seminal works by some of the twentieth century’s most important artists. Considered as a group, the works in this exhibition articulate the transition from Romantic expressionism to cool literalism that occurred in the past century, a shift brought about by figuration’s evolution into abstraction and then by an eschewal of the image altogether in favour of the conceptual. These artists fundamentally influenced the course of art, combining radical innovation with wit and intelligence.

The earliest work on display is an important painting by Piet Mondrian — Beach with one Pier at Domburg (Dune), one of a series executed by the artist in 1909, each testing a different style across the same motif. Through heightened colours Mondrian sought to create an all-encompassing art, which he believed to be beyond the possibilities of traditional painting. These paintings occupy a key place within Mondrian’s trajectory, representing the very beginnings of his path to abstraction: ‘The first thing to change in my painting was colour. I forsook natural colour for pure colour.’

Search is considered to be the last painting Jackson Pollock made and featured in his exhibition at Sydney Janis, New York in 1955. According to the art historian Elizabeth Frank ‘his late paintings are some of his most inventive and assured works, paintings of marked freedom and individuality.... Search maps out an unexpected all over synthesis between the puddle shapes of the black paintings and the semi-enclosed angles and contours of his pre-1947 paintings.’

The controlled abandon of Pollock’s gestures are a precursor to, but hardly a preparation for, Joan Mitchell’s Mandres (1961 – 1962) where rhythm and vibrancy are displaced for seemingly primordial matter. Made at a difficult time in the artist’s life, this extraordinary painting’s dark amorphous mass of opacities bear every possible means of her hand’s making. Yet for all the furies that Mitchell unleashed on her canvas, its facture was highly considered: “The freedom in my work is controlled,” she said, “If I want to undertake the act of painting in full liberty, I want to know what my brush is about to do.”

In contrast, Yves Klein turned to the elements to make his Cosmogony (1961), allowing rain to corrode an image into his International Klein Blue. Through colour, Klein aimed to express a world beyond the material, explaining: ‘before the coloured surface one finds oneself directly before the matter of the soul’, whilst provocatively undermining the transcendence of his gestures through his decision to trademark his pigment.

For Piero Manzoni the Sublime was to be looked for through the eradication of colour, yet even then his canvases remained impossibly impure. His Achrome (1959), literally ‘without colour’, is an early example of the series that made his reputation and which he continued until his early death. This series of all-white works began simply as folded sheets of cotton coated in kaolin (a fine clay used in porcelain), but increasingly introduced more artificial elements culminating in blond fibreglass curls. Manzoni allowed the material he used dictate his work. ‘It is not a question of shaping things, nor of articulating messages,’ he argued, ‘for are not fantasising, abstraction and self-expression empty fictions? There is nothing to be said: there is only to be, to live.’

Sharing with Manzoni a commitment to white, Robert Ryman narrowed his parameters further to mount a systematic investigation into the matter of paint. In Signet 20 (1965 – 1966) a two-inch wide brush has been charged with white oil paint and dragged from left to right across the canvas, with each swipe covering eight or so inches before having to be reloaded, forming fractured parallel lines that reveal the canvas below. Ryman often allowed his tools and paints to dictate a work’s title, and in this instance named the painting after the make and size of his chosen brush. Expunging any references in his works beyond his materials, Ryman made paint ‘the content of the paintings as well as the form.’

Matter and pigment are one in Blinky Palermo’s Blaue Scheibe und Stab (Blue Disc and Stick) (1968), whose powerful colour is inherent to the fabric tape that forms the outer surface of the forms. The composite sculpture is described by the art historian Benjamin H D Buchloh as one of his ‘absolute favourites ... an extraordinary conception in terms of material execution.’ Its blue bandaging arouses pathos whilst being fundamental to its construction. For the critic Jan Verwoert, in Palermo’s pieces ‘the sensation of seeing a sublime work was grounded in a bodily reality, the reality of which transformed the purity of the colour panels into something broken, intimate and almost tender.’

On Kawara’s Dec. 28, 1971 conveys little other than the existence of the artist when he painted it. His ‘Date Paintings’ are testaments to consciousness anchored, through the language and conventions of their script, to the country where they were made. Numbers and letters have been painstakingly hand drawn and painted to appear as impersonal as if made by a machine. For all their extreme reductivism and negation of expression, Kawara’s paintings possess an emotional force and metaphoric reach, eloquent precisely because of their uncompromising factuality.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s auratic Untitled (for New York) (1992) made from 42 light bulbs is one of 25 light string sculptures whose parenthetical titles point to memories or events that were important to him. In these, readily available hardware is used to conjure numerous associations: light as a symbol of spirituality and enlightenment, as a haven and source of warmth, and of life, as impermanent as each ephemeral bulb. Like memory, the meanings of each piece remain personal and mutable. There is no set instruction for how it should be installed, and in this way Gonzalez-Torres allows for continuous reinterpretation, democratically involving others in the making of the work. His aim was to move viewers to a ‘place of beauty, freedom, pleasure.’