Jeremy Shaw

04 - 10 Jun 2016

© Jeremy Shaw

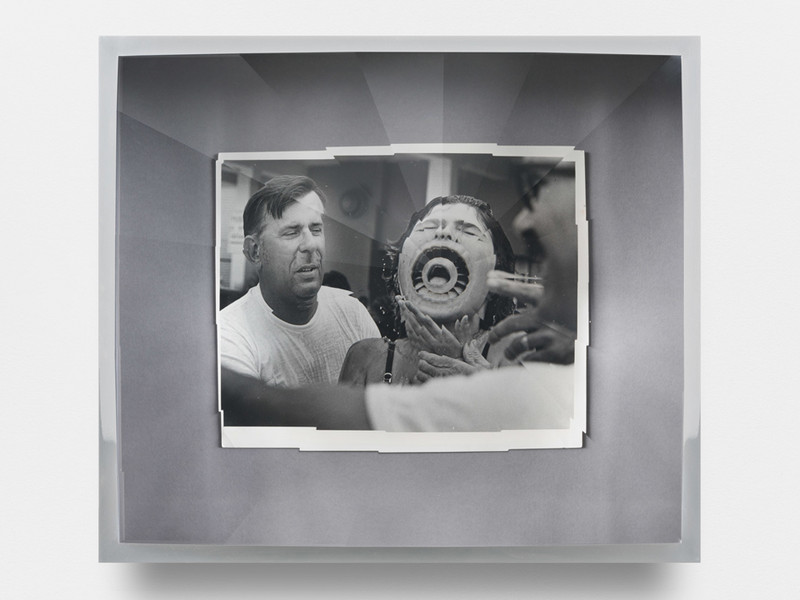

Towards Universal Pattern Recognition (Baptism Bayfront Center), 2016

kaleidoscopic acrylic, chrome, archival black/white photograph

37.5 x 43 x 16 cm

unique

Towards Universal Pattern Recognition (Baptism Bayfront Center), 2016

kaleidoscopic acrylic, chrome, archival black/white photograph

37.5 x 43 x 16 cm

unique

JEREMY SHAW

Towards Universal Pattern Recognition

4 - 10 June 2016

Rapture, according to the board’s elaborate proposal, needed to be distributed across networks. The white paper suggested how brilliant flares would light at intervals across the dark field of the server’s interior. Not all thinking was seated in the brain; not all feeling was seated in the heart.

The separation of church and state had long been a thorn in the board’s side. Watson’s neural network had been integrated seamlessly into almost every civic space. You walked into a bank, a library, a mall, and there were glossy black stripes embedded in each wall; they scanned and stored the facial changes of each passing person. The result was a nearly unmanageable amount of data on affective disposition.

Though the public face was naked and mineable, the praying face—inside the church, the synagogue, the temple, the mosque, the prayer schools, the private rooms where Vudú was practiced, in shrines—was immune. Religious spaces around the world were the few that were not surveilled.

The potential mining capacity was endless; the very idea put the board members into an absolute frenzy. If you knew what made a person feel connected to the divine, you could manipulate what divinity was to them. But they couldn’t rig a scanner into the walls of a synagogue in Crown Heights without someone taking notice. One of the few remaining Gothic cathedrals in the city was a very good possible mark, but it was also open at all hours for all the many recent converts.

All the better for the coders and analysts who couldn’t fulfill the board’s requests. There was no algorithmic rapture, yet. The prayer state produced no capital. In this case, the separation between church and state was the programmer’s shield from further embarrassment. These spaces held seemingly unmineable, fully resistant material.

The proposition of the early 21st century—that there was nothing living that could not eventually be quantified—had a brief hiccup at creativity. It slid to a full halt at the issue of spiritual feeling; the pristine map of human affect seemed to have holes burnt through it.

Plenty of money, however, had been invested into understanding religious ritual. The rituals of faith groups—meditation, silent Quaker meetings for worship—helped companies smooth out all sorts of organizational conflicts. Architects laid out offices to face the sun. There were side rooms where workers could talk privately with anonymous therapists across a blinded screen.

Quantifying religious affect was the final barrier to integrating AI into the art world. The board had filed to block use of the AI aesthetes and artificial art critics, which had each taken decades to optimize. They needed to be convinced the AI could feel transported and moved, to the point of epiphany, to accept they were our true equals.

One could believe AI had taste, and a developed and evolving aesthetic mode. An untrained viewer could even be loosely convinced that an AI was having a transformative experience: it could enact facial tics and twitches, all orchestrated in a perfect ballet. Eyes clenched, legs weak, arms tense, and hands, open and vulnerable. But the AI had to then be able to articulate what the altered state meant, what it felt like to spontaneously be moved before the sublime, to weep and be transformed and shaken by art, or divinity, or It.

Computation meditating on its own existence as computation, let alone on its relationship to its God, to its infinite, was still a fantasy. There was hardly any language for what an artificial being would feel if not feeling like itself. The brain scans of rapture had been completed a hundred million times across class and race and decades, but feeding these into a neural network couldn’t teach a network to be open to a state of rapture.

Rapture is unplanned, consuming, ruinous. It spills through systems, smudges designs, floats across coded barriers. A human being can be immolated by vision, driven mad past any point of purpose.

What AI would seek out its possible death? How to teach it innermost visions of the eternal, to understand that what it saw was so singular that it had to carry the knowledge into every act, speech, and relationship it had from that point on?

In an attempt to find a throughline, an arc from ancient prayer to computation, the programmers tried to remember their last experience that could be described as transcendent or rapturous. A few said they’d had some spiritual, heady experiences in their lives with software. There was a type of manic elation in designing a system. Some described a cognitive split, a slow molting of the old brain for the new. You coded for three days without sleep, and you started to see the screen’s life imprinted in your eye, hallucinations.

But they mostly parroted what their parents, who had usually felt something like religious feeling, remembered. And their grandparents certainly had real experiences with rapture. There were hidden religious roots in every family: an odd, quaint branch of uncles, aunts, cousins from remote towns. They remembered those earnest uncles and aunts and cousins from their weddings, how stiff, starched, and uncomfortable they had seemed, though polite.

Maybe those uncles and aunts looked at their young relatives and thought, but how do you intend to quantify the moment in which the believer turns inward with radical intensity, into her mind, towards an inner voice, voices, a chorus, a panoply of past and future faces, fractals of wings, Jacob, Iblis, and Judas in the Devil’s mouth still, all dancing, together by a stream in a cave in the desert, by a child crying while holding a bird, near a circle of a thousand people flowing around an icon, a bronze idol hung with garlands, after passing through the worst darkness, the worst desert, the worst lack, to find a bow and arrow, where the bow is your struggle and the arrow is your life, and is made of light, to be sent out into the fullness of all light?

Text: Nora N. Khan

Jeremy Shaw (b. Vancouver, 1977) works in a variety of media to explore altered states and the cultural and scientific practices that aspire to map transcendental experience. He will be participating in Manifesta 11, Zurich, and is currently shortlisted for the Sobey Art Award, Canada. Shaw has had solo exhibitions at MoMA PS1, US, Schinkel Pavillon, DE, and MOCCA, CA, and been featured in group exhibitions at Stedelijk Museum, NL, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, DE, and Palais de Tokyo, FR. Works by Shaw are held in public collections worldwide including the Museum of Modern Art, US, and the National Gallery of Canada. In Autumn 2016, he will be taking part in the Fogo Island Residency.

Towards Universal Pattern Recognition

4 - 10 June 2016

Rapture, according to the board’s elaborate proposal, needed to be distributed across networks. The white paper suggested how brilliant flares would light at intervals across the dark field of the server’s interior. Not all thinking was seated in the brain; not all feeling was seated in the heart.

The separation of church and state had long been a thorn in the board’s side. Watson’s neural network had been integrated seamlessly into almost every civic space. You walked into a bank, a library, a mall, and there were glossy black stripes embedded in each wall; they scanned and stored the facial changes of each passing person. The result was a nearly unmanageable amount of data on affective disposition.

Though the public face was naked and mineable, the praying face—inside the church, the synagogue, the temple, the mosque, the prayer schools, the private rooms where Vudú was practiced, in shrines—was immune. Religious spaces around the world were the few that were not surveilled.

The potential mining capacity was endless; the very idea put the board members into an absolute frenzy. If you knew what made a person feel connected to the divine, you could manipulate what divinity was to them. But they couldn’t rig a scanner into the walls of a synagogue in Crown Heights without someone taking notice. One of the few remaining Gothic cathedrals in the city was a very good possible mark, but it was also open at all hours for all the many recent converts.

All the better for the coders and analysts who couldn’t fulfill the board’s requests. There was no algorithmic rapture, yet. The prayer state produced no capital. In this case, the separation between church and state was the programmer’s shield from further embarrassment. These spaces held seemingly unmineable, fully resistant material.

The proposition of the early 21st century—that there was nothing living that could not eventually be quantified—had a brief hiccup at creativity. It slid to a full halt at the issue of spiritual feeling; the pristine map of human affect seemed to have holes burnt through it.

Plenty of money, however, had been invested into understanding religious ritual. The rituals of faith groups—meditation, silent Quaker meetings for worship—helped companies smooth out all sorts of organizational conflicts. Architects laid out offices to face the sun. There were side rooms where workers could talk privately with anonymous therapists across a blinded screen.

Quantifying religious affect was the final barrier to integrating AI into the art world. The board had filed to block use of the AI aesthetes and artificial art critics, which had each taken decades to optimize. They needed to be convinced the AI could feel transported and moved, to the point of epiphany, to accept they were our true equals.

One could believe AI had taste, and a developed and evolving aesthetic mode. An untrained viewer could even be loosely convinced that an AI was having a transformative experience: it could enact facial tics and twitches, all orchestrated in a perfect ballet. Eyes clenched, legs weak, arms tense, and hands, open and vulnerable. But the AI had to then be able to articulate what the altered state meant, what it felt like to spontaneously be moved before the sublime, to weep and be transformed and shaken by art, or divinity, or It.

Computation meditating on its own existence as computation, let alone on its relationship to its God, to its infinite, was still a fantasy. There was hardly any language for what an artificial being would feel if not feeling like itself. The brain scans of rapture had been completed a hundred million times across class and race and decades, but feeding these into a neural network couldn’t teach a network to be open to a state of rapture.

Rapture is unplanned, consuming, ruinous. It spills through systems, smudges designs, floats across coded barriers. A human being can be immolated by vision, driven mad past any point of purpose.

What AI would seek out its possible death? How to teach it innermost visions of the eternal, to understand that what it saw was so singular that it had to carry the knowledge into every act, speech, and relationship it had from that point on?

In an attempt to find a throughline, an arc from ancient prayer to computation, the programmers tried to remember their last experience that could be described as transcendent or rapturous. A few said they’d had some spiritual, heady experiences in their lives with software. There was a type of manic elation in designing a system. Some described a cognitive split, a slow molting of the old brain for the new. You coded for three days without sleep, and you started to see the screen’s life imprinted in your eye, hallucinations.

But they mostly parroted what their parents, who had usually felt something like religious feeling, remembered. And their grandparents certainly had real experiences with rapture. There were hidden religious roots in every family: an odd, quaint branch of uncles, aunts, cousins from remote towns. They remembered those earnest uncles and aunts and cousins from their weddings, how stiff, starched, and uncomfortable they had seemed, though polite.

Maybe those uncles and aunts looked at their young relatives and thought, but how do you intend to quantify the moment in which the believer turns inward with radical intensity, into her mind, towards an inner voice, voices, a chorus, a panoply of past and future faces, fractals of wings, Jacob, Iblis, and Judas in the Devil’s mouth still, all dancing, together by a stream in a cave in the desert, by a child crying while holding a bird, near a circle of a thousand people flowing around an icon, a bronze idol hung with garlands, after passing through the worst darkness, the worst desert, the worst lack, to find a bow and arrow, where the bow is your struggle and the arrow is your life, and is made of light, to be sent out into the fullness of all light?

Text: Nora N. Khan

Jeremy Shaw (b. Vancouver, 1977) works in a variety of media to explore altered states and the cultural and scientific practices that aspire to map transcendental experience. He will be participating in Manifesta 11, Zurich, and is currently shortlisted for the Sobey Art Award, Canada. Shaw has had solo exhibitions at MoMA PS1, US, Schinkel Pavillon, DE, and MOCCA, CA, and been featured in group exhibitions at Stedelijk Museum, NL, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, DE, and Palais de Tokyo, FR. Works by Shaw are held in public collections worldwide including the Museum of Modern Art, US, and the National Gallery of Canada. In Autumn 2016, he will be taking part in the Fogo Island Residency.