Leiko Ikemura

Woman of Fire Dancing with Tree

21 Apr - 17 Jun 2017

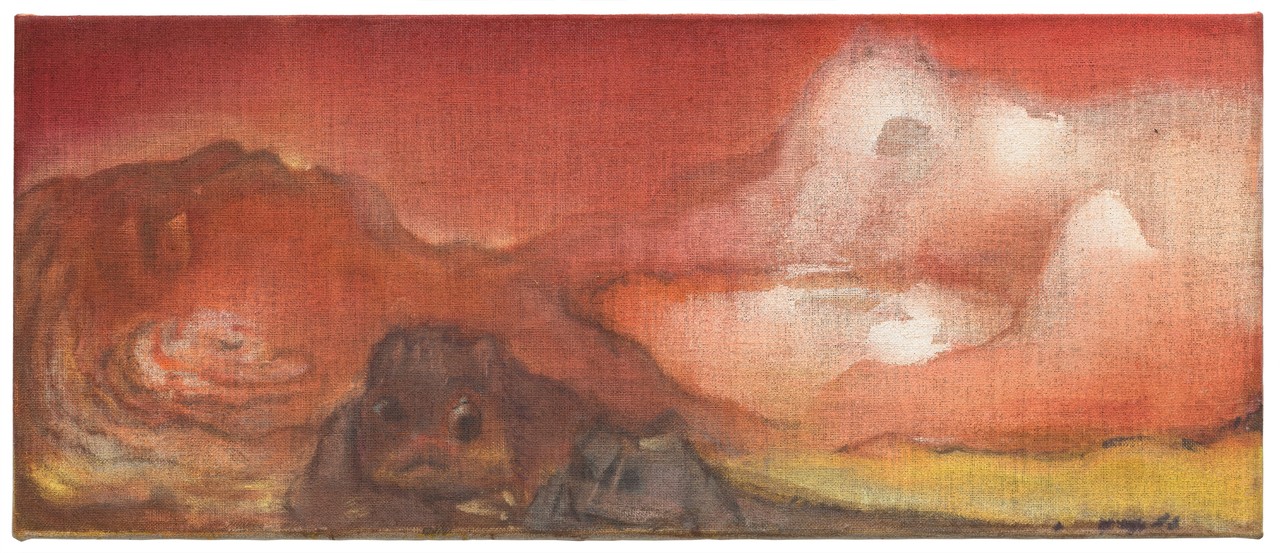

Leiko Ikemura, Genesis with St. Ursula, 2016, Tempera and oil on jute, 190 x 290 cm / 74 3/4 x 114 1/4 in

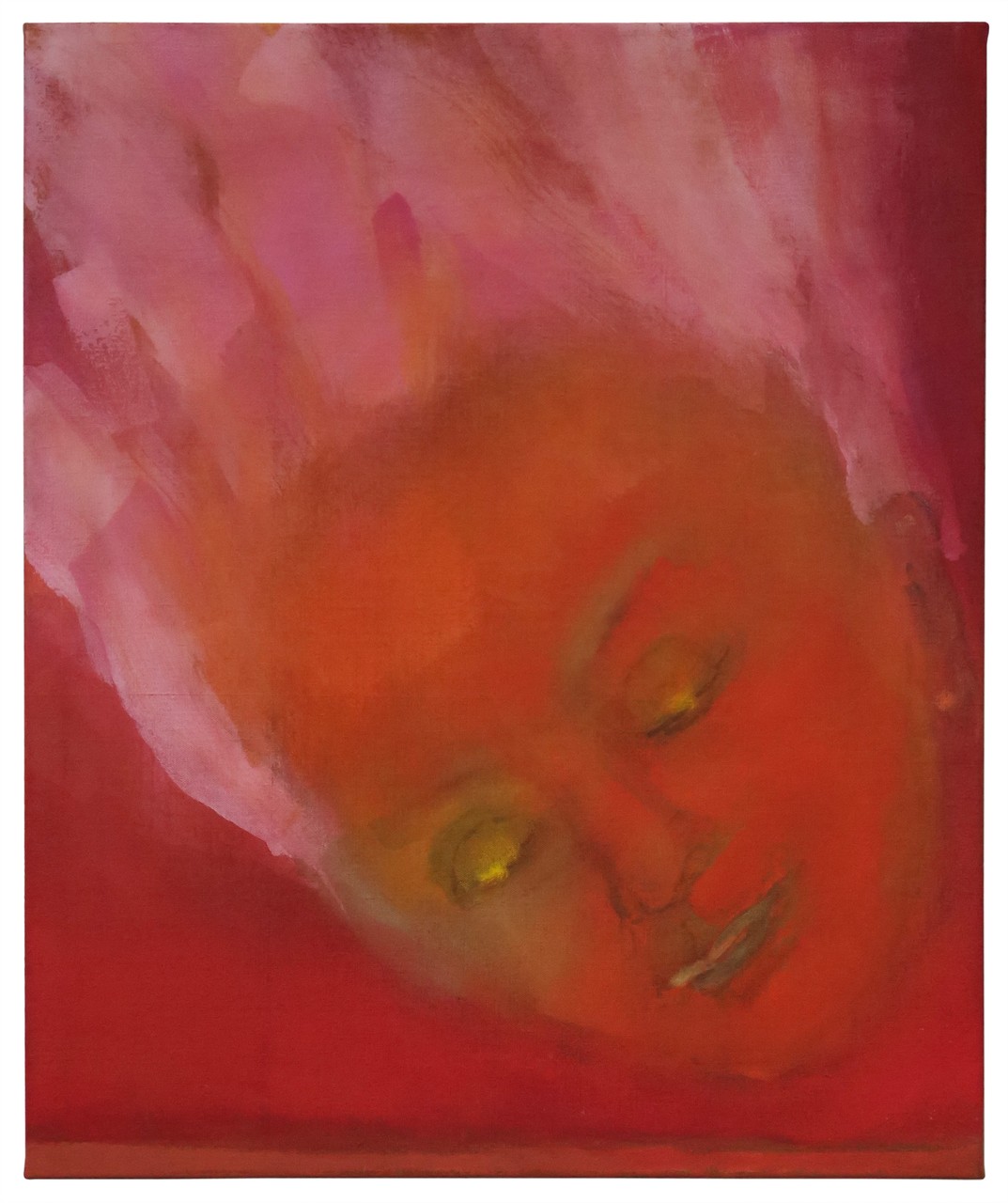

Leiko Ikemura, Face with Pink Hair, 2016, Tempera on jute, 120 x 100,5 x 3,2 cm / 47 1/4 x 39 1/3 in

Galerie Karsten Greve is pleased to announce the exhibition Woman of Fire Dancing with Tree, a comprehensive solo-show presenting new works by Leiko Ikemura. The exhibition, is staged in celebration of the 30-year collaboration between Karsten Greve and the artist, which began with a solo-show in 1987 in the gallery’s former exhibition space located at Wallrafplatz in Cologne. A publication with texts by Dr. Katharina Winnekes and Dr. Barbara J. Scheuermann will accompany the exhibition.

The plethora of media in which Leiko Ikemura’s oeuvre expresses itself encompasses painting, sculpture and drawing as artistic genres. Its motifs, mainly centered on themes of embodiment and transformation, reflect both the artist’s formal autonomy as well as flexible dexterities and artistic skillset. In her fairytale scenarios, evocative of a dream-like sensibility and inhabited by hybrid creatures, cats, birds and girls merge while humanoid figures and landscape formations amalgamate, telling of metamorphosis and mutations.

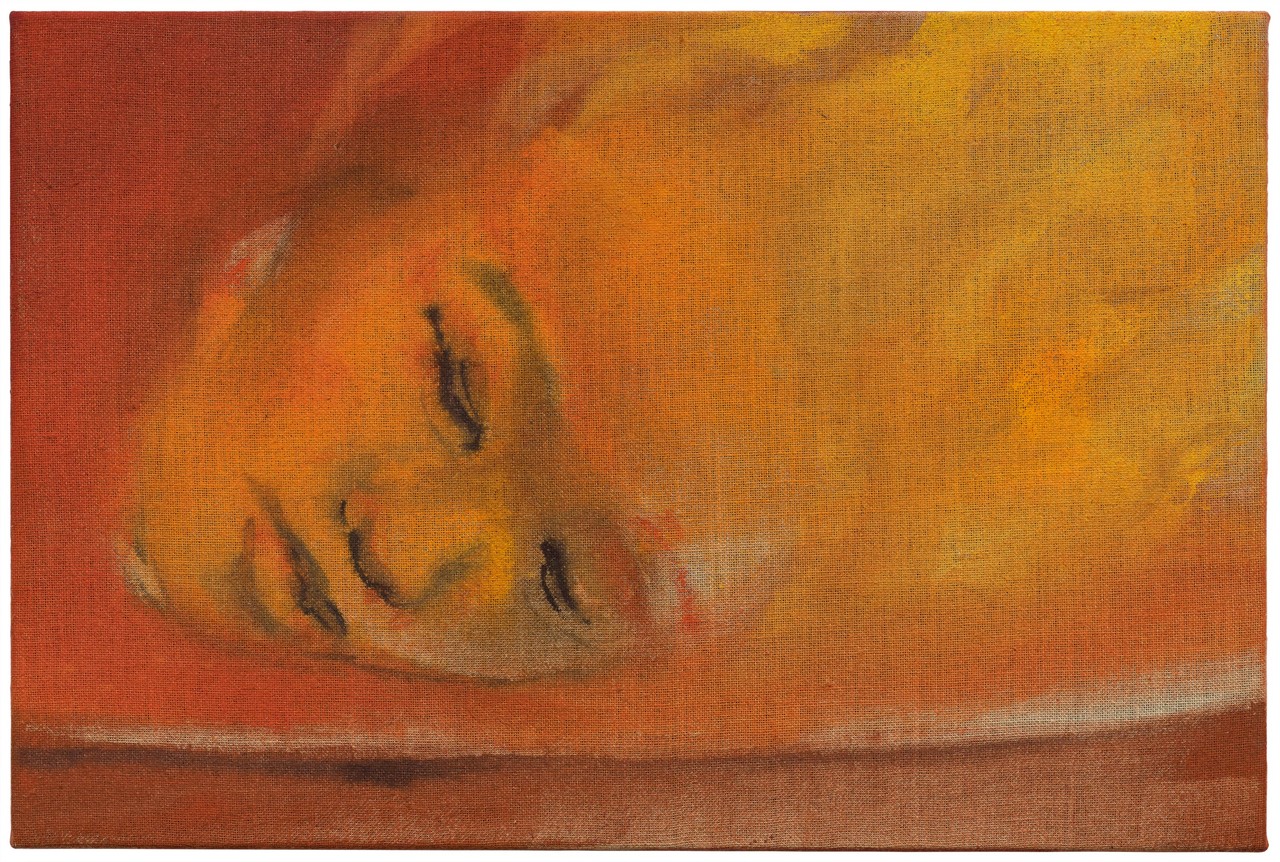

Shapes are often merely alluded to and not fully fleshed out, only rendering themselves visible in their entirety upon intent study, then dissipating at a breath of wind. Hazy wafts of mist conciliate bodies of water with mountainous vistas, dissolve the horizon and then condense into faces appearing abruptly like a chimaera. Akin to a figure-ground illusion, the curvature of the river bend is also the outline of a graciously swung body. Figurines turn into ghostly entities, manifestations of nature in its most intrinsic form. Floating, disembodied heads with hair ablaze in flames, emblematic of the element fire – or perhaps the embodiment of a petulant force of nature – appear at times gentle and alternatingly tumultuous (Floating Storm, Haruko). In Ikemura’s Trees series, a typology of temperament in which the crowns of the trees are in either a hot-tempered, sanguine turmoil or a state of downtrodden melancholia, the trees reveal themselves as manifold variations of individual personalities. Occasionally the gold dust embellishment of the surface suggests a reference to alchemy, a tenet primarily concerned with the transfer of energy in the transmutation of base metals into gold and silver.

Ikemura’s cosmology of flux and transformation follows a pantheistic worldview, according to which god is inherent in all things. Plato had defined this omnipresent world-soul as “self-moving motion”. In the context of a cosmic framework but also within the individual, the soul is the origin of life, liaising between the mind and body, between being and becoming. As the ultimate impetus for creation, it transmutes inanimate matter into living creatures; a piercing creative energy that brings with it change, conforming to the cosmological law defined by Heraclitus in the Panta Rhei formula as eternal flow: “All entities move and nothing remains still”.

Leiko Ikemura’s works transport the variability of a constantly evolving body of work, in which also the unique qualities of the materials are seminally exploited as productive potential throughout the artistic process. While in traditional art theory, the ambition is to transform raw material into sublime form through either the mastery or even subjugation of the working material, Ikemura grants the material a creative intrinsic value of its own. The untamed essence of the substance, which erupts like volcanic lava and leaves an aftermath of earthen lumps and amorphous clusters, takes shape in the artist’s terracotta sculptures. An unpredictable drive inheres in the sculpted form, a transformative energy at its core that seeks to pierce through its surface. Often the moment of transmutation seems to occur while in an outward state of deep slumber, so that sleeping heads are rendered as stones while life unfolds at an unhurried pace, trees sprouting from the surface of a face. The natural and untreated quality of the jute, which Ikemura uses for her paintings, possesses a distinct appeal. Its rustic surface texture permeates to the surface of the works as the elements within the composition – articulated with a glaze of watered down tempera – interact in a manner brimming with tension.

eiko Ikemura’s creation myths are sensitive reflections of artistic creativity that incorporate different cultures and religions. The artist herself draws from multiple sources and traditions. After studying Spanish literature in her native Japan, she emigrated to Spain in 1972. From 1973 until 1978 she studied painting at the art academy in Sevilla. After moving to Switzerland she became part of the art scene in Zurich, leaving a lasting impact. In 1983, the Bonner Kunstverein showed her works for the first time. Numerous solo and group shows followed, such as the exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Basle, Switzerland in 1987. Aside from distinguished international shows throughout the years her work was last displayed in a memorable presentation in the Museum of Eastern Asian Art in Cologne in 2016. As she freely moves between the continents, Ikemura internalizes myths and legends, incorporating universal imagery into her pictorial language. Her repository of motifs contains archaic shapes, which, like archetypes, reference existential conditions as well as the origins of the human experience.

The plethora of media in which Leiko Ikemura’s oeuvre expresses itself encompasses painting, sculpture and drawing as artistic genres. Its motifs, mainly centered on themes of embodiment and transformation, reflect both the artist’s formal autonomy as well as flexible dexterities and artistic skillset. In her fairytale scenarios, evocative of a dream-like sensibility and inhabited by hybrid creatures, cats, birds and girls merge while humanoid figures and landscape formations amalgamate, telling of metamorphosis and mutations.

Shapes are often merely alluded to and not fully fleshed out, only rendering themselves visible in their entirety upon intent study, then dissipating at a breath of wind. Hazy wafts of mist conciliate bodies of water with mountainous vistas, dissolve the horizon and then condense into faces appearing abruptly like a chimaera. Akin to a figure-ground illusion, the curvature of the river bend is also the outline of a graciously swung body. Figurines turn into ghostly entities, manifestations of nature in its most intrinsic form. Floating, disembodied heads with hair ablaze in flames, emblematic of the element fire – or perhaps the embodiment of a petulant force of nature – appear at times gentle and alternatingly tumultuous (Floating Storm, Haruko). In Ikemura’s Trees series, a typology of temperament in which the crowns of the trees are in either a hot-tempered, sanguine turmoil or a state of downtrodden melancholia, the trees reveal themselves as manifold variations of individual personalities. Occasionally the gold dust embellishment of the surface suggests a reference to alchemy, a tenet primarily concerned with the transfer of energy in the transmutation of base metals into gold and silver.

Ikemura’s cosmology of flux and transformation follows a pantheistic worldview, according to which god is inherent in all things. Plato had defined this omnipresent world-soul as “self-moving motion”. In the context of a cosmic framework but also within the individual, the soul is the origin of life, liaising between the mind and body, between being and becoming. As the ultimate impetus for creation, it transmutes inanimate matter into living creatures; a piercing creative energy that brings with it change, conforming to the cosmological law defined by Heraclitus in the Panta Rhei formula as eternal flow: “All entities move and nothing remains still”.

Leiko Ikemura’s works transport the variability of a constantly evolving body of work, in which also the unique qualities of the materials are seminally exploited as productive potential throughout the artistic process. While in traditional art theory, the ambition is to transform raw material into sublime form through either the mastery or even subjugation of the working material, Ikemura grants the material a creative intrinsic value of its own. The untamed essence of the substance, which erupts like volcanic lava and leaves an aftermath of earthen lumps and amorphous clusters, takes shape in the artist’s terracotta sculptures. An unpredictable drive inheres in the sculpted form, a transformative energy at its core that seeks to pierce through its surface. Often the moment of transmutation seems to occur while in an outward state of deep slumber, so that sleeping heads are rendered as stones while life unfolds at an unhurried pace, trees sprouting from the surface of a face. The natural and untreated quality of the jute, which Ikemura uses for her paintings, possesses a distinct appeal. Its rustic surface texture permeates to the surface of the works as the elements within the composition – articulated with a glaze of watered down tempera – interact in a manner brimming with tension.

eiko Ikemura’s creation myths are sensitive reflections of artistic creativity that incorporate different cultures and religions. The artist herself draws from multiple sources and traditions. After studying Spanish literature in her native Japan, she emigrated to Spain in 1972. From 1973 until 1978 she studied painting at the art academy in Sevilla. After moving to Switzerland she became part of the art scene in Zurich, leaving a lasting impact. In 1983, the Bonner Kunstverein showed her works for the first time. Numerous solo and group shows followed, such as the exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Basle, Switzerland in 1987. Aside from distinguished international shows throughout the years her work was last displayed in a memorable presentation in the Museum of Eastern Asian Art in Cologne in 2016. As she freely moves between the continents, Ikemura internalizes myths and legends, incorporating universal imagery into her pictorial language. Her repository of motifs contains archaic shapes, which, like archetypes, reference existential conditions as well as the origins of the human experience.