Louise Bourgeois

Works on Paper

02 Mar - 07 Apr 2018

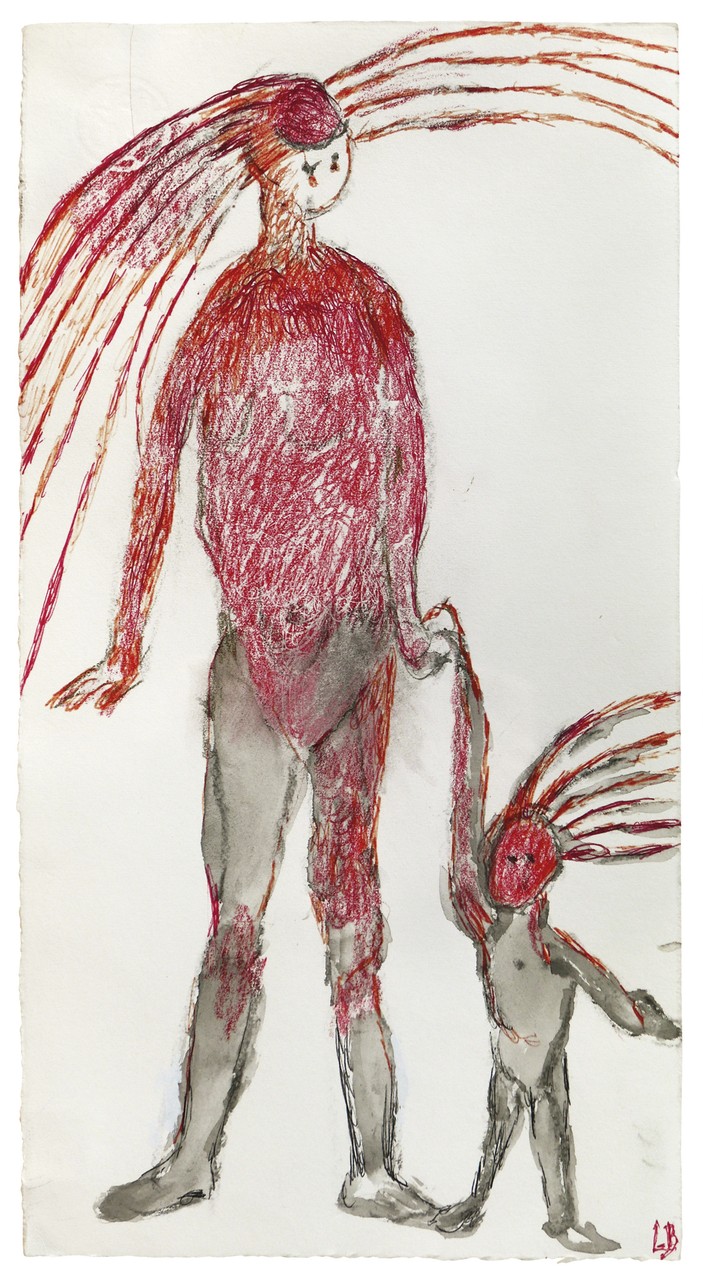

Louise Bourgeois, Untitled, 2002, watercolor, crayon, ink and charcoal on paper

39,9 x 20,9 cm / 15 2/3 x 8 1/4 in;

Photo: Christopher Burke, New York

39,9 x 20,9 cm / 15 2/3 x 8 1/4 in;

Photo: Christopher Burke, New York

Louise Bourgeois, Femme, 2007, pencil and gouache on paper

37,4 x 27,9 cm / 14 3/4 x 11 in

Photo: Christopher Burke, New York

37,4 x 27,9 cm / 14 3/4 x 11 in

Photo: Christopher Burke, New York

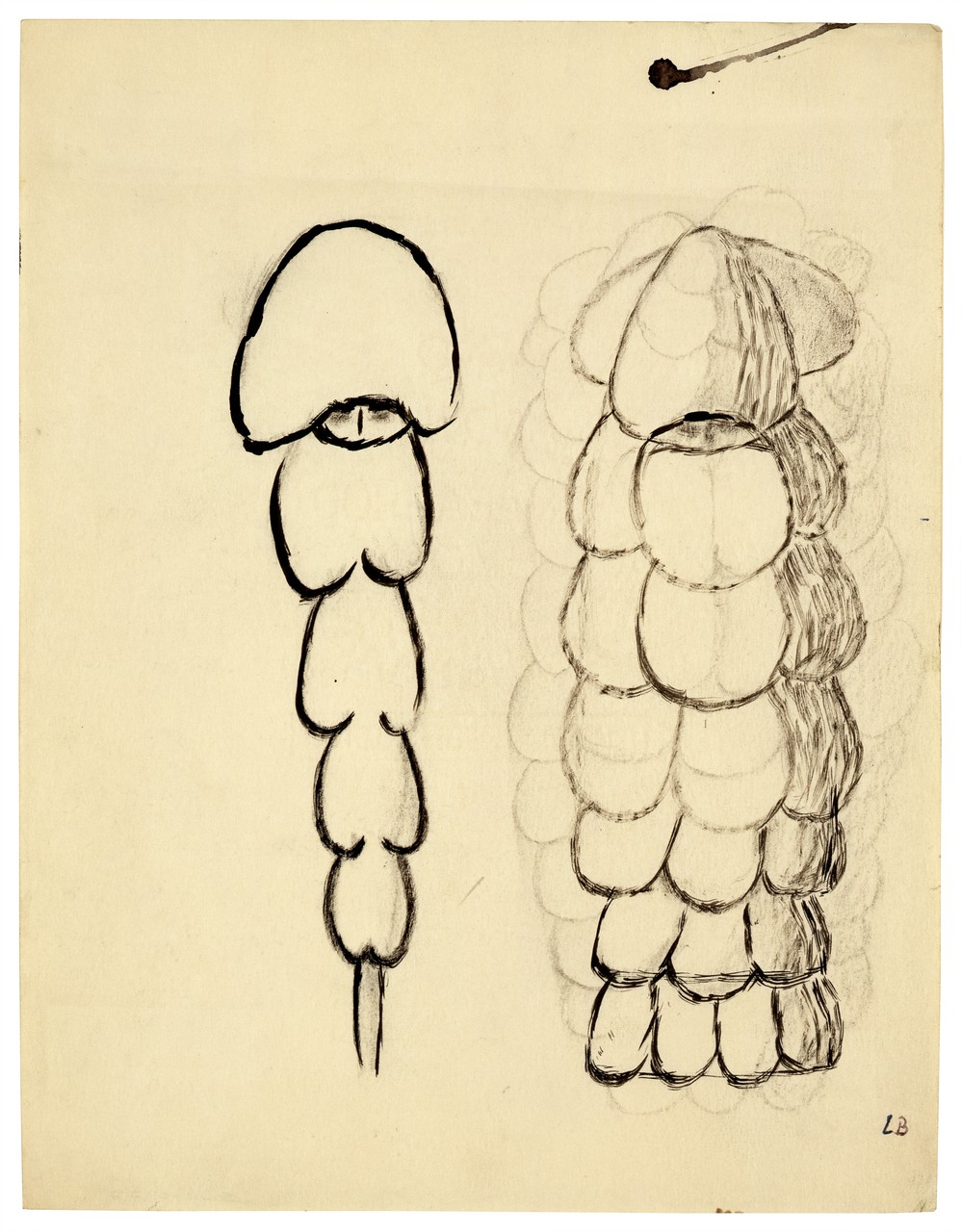

Louise Bourgeois, Untitled, 1951, ink and charcoal on paper

28 x 20,1 cm / 11 x 8 in

Photo: Jochen Littkemann

28 x 20,1 cm / 11 x 8 in

Photo: Jochen Littkemann

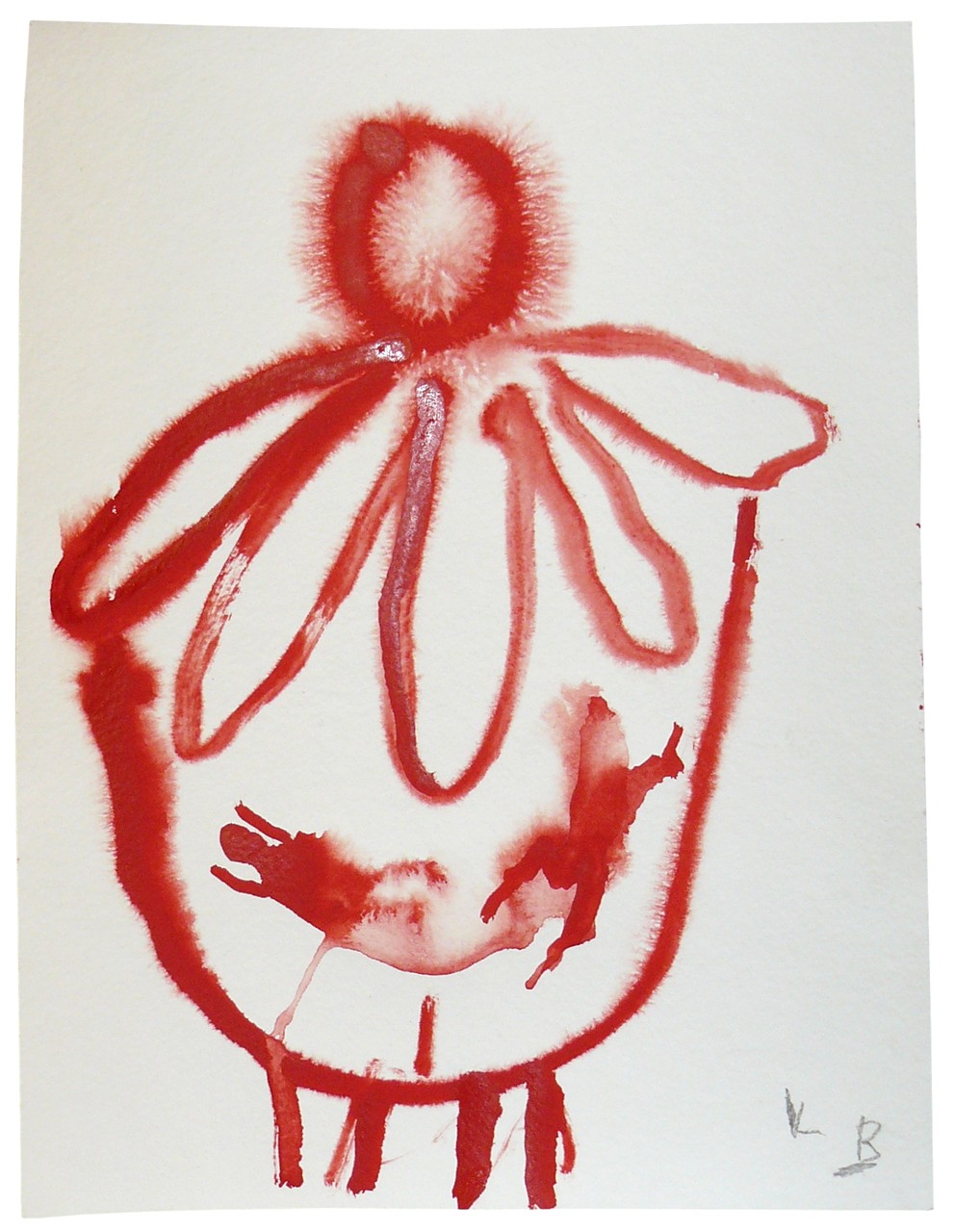

Louise Bourgeois, Untitled, 2007, watercolor on paper, 29,3 x 22,8 cm;

Photo: Galerie Karsten Greve Cologne Paris St. Moritz

Photo: Galerie Karsten Greve Cologne Paris St. Moritz

Louise Bourgeois, Untitled, 1947, ink and charcoal on paper,

27,9 x 19 cm / 11 x 7 1/2 in

Photo: Friedrich Rosenstiel

27,9 x 19 cm / 11 x 7 1/2 in

Photo: Friedrich Rosenstiel

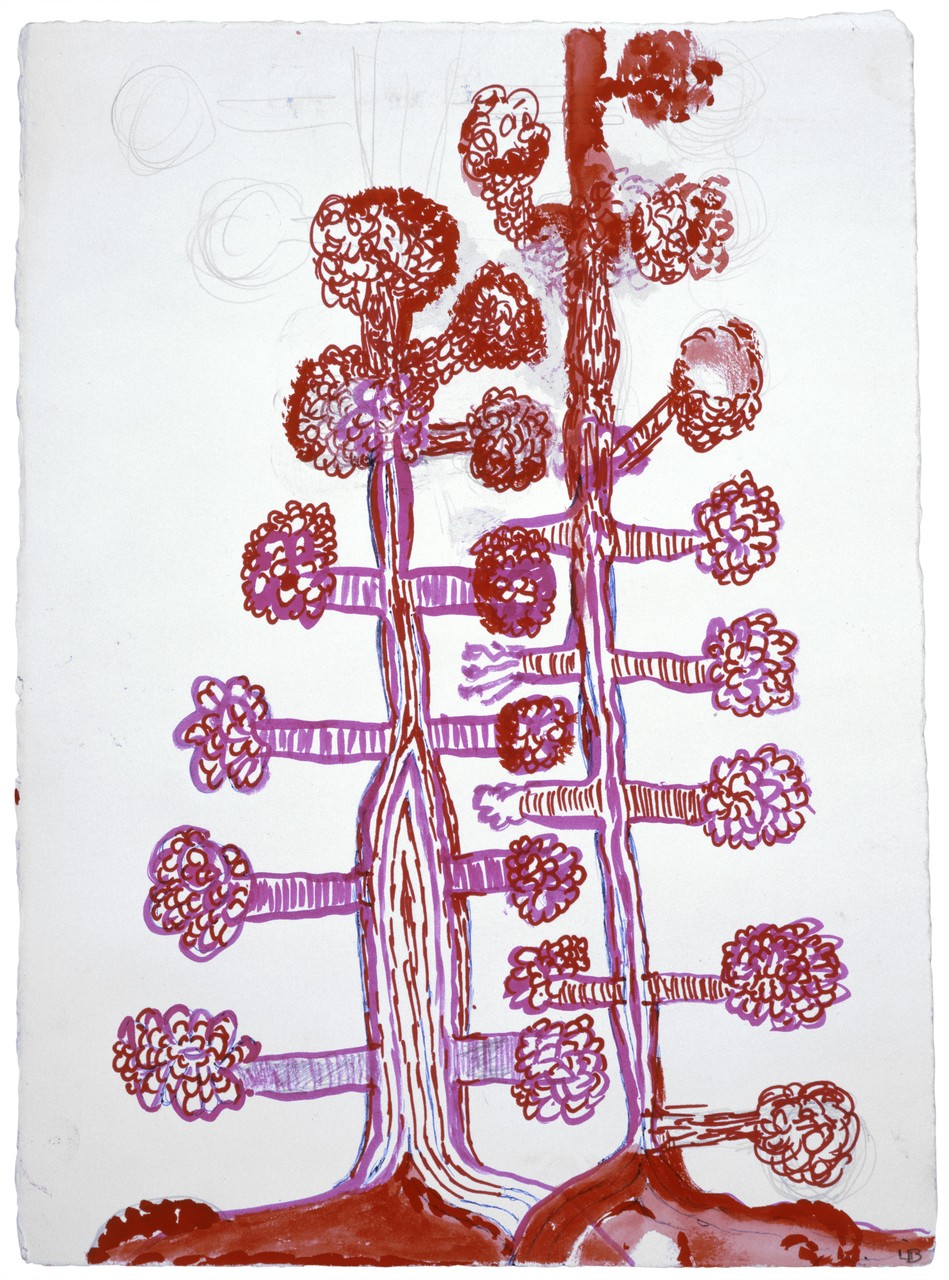

Louise Bourgeois, Untitled, 1997, watercolor, ink, pencil and opaque white on paper, 38,1 x 28,5 cm / 15 x 11 1/4 in

Photo: Christopher Burke, New York

Photo: Christopher Burke, New York

In a unique compilation, Galerie Karsten Greve is presenting drawings by Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010) produced over a period of six decades. The selection of works, dating from 1947 to 2007, comes from the private collection of Karsten Greve and reflects the long-standing collaboration with Louise Bourgeois, which, in numerous exhibitions, illuminated all the phases of this œuvre of a century with its wealth of allusions, until the death of the artist at the age of 98. After she had followed her husband to the United States as early as 1938, it was Karsten Greve who, in 1990, staged the very first exhibition for her in her native France in his Paris gallery, which had opened the year before. In addition, a comprehensive show with works by Louise Bourgeois marked the opening of the gallery’s St. Moritz branch in 1999.

Louise Bourgeois’s earliest striking charcoal and ink works date back to 1947, the heyday of her graphic work, which developed dynamically between painting and sculpture, in other words at the interface between surface and depth. The block-like forms, looking as if carved in stone, correspond with the contemporaneous vertical, statuesque stelae of the Personnages group of sculptures, and can be seen as representations of people who were close to her but no longer by her side after she left her French homeland for America.

The jagged lines and energetic hatchings of other works produced at this time also relate to the rugged cliffs and steep slopes of the landscape in the Creuse region of central France, where Bourgeois grew up. The artist described the harsh mountain region as ‘abandoned and sterile’. After the black, sharply contoured forms of the late 1940s and early 1950s, Bourgeois turned, with increasing fluency in her stroke – now using thin watercolour ranging from delicate tones to bright red – to a soft anthropomorphic landscape in which the resolution is the form-giving element. In this process, mountains turn into breasts and trees into phallic pillars, while the boundaries between human form, mountains and plants become fluid. In the late drawings by the then 96-year-old artist in 2007, forms appear to take on a life of their own and to multiply, female and male features permeate each other in a creative dynamism of mutations and metamorphoses, so that any clear categorization becomes obsolete. The variety of polymorphic manifestations reveals at the same time the complexity of the artist’s psychology, characterized by the turbulent circumstances of her life.

For Louise Bourgeois, the ‘artwork is a language’ whose origin is to be found in mental states. The artist considered the drawing an immediate method of recording psychological realities and expressions of the subconscious. Like the spontaneous, unfiltered écriture automatique of the Surrealists, the pen functions as an instrument for rediscovering memories, as a seismograph of the soul. Personal experiences are symbolically condensed and achieve pictorial expression. Thus, in Bourgeois’s work, forms appear as powerful signs of a highly subjective reality, as primal elements of emotion.

Louise Bourgeois’s source of inspiration always lay in her past. In particular, childhood experiences and memories of her childhood home were the starting point for a groundbreaking fantasy. ‘The creative impulse for all my work is to be found in my childhood.’ The intensity of the emotional content had its roots in the unstable family configuration of father, mother and governess, who was also the father’s lover. The pictorial worlds of the artist, whose primary motivation was always self-representation in the sense of the visualization of a personal, albeit fragile, self-image, revolve again and again around this love triangle and the resulting emotional entanglements.

Her motifs, like an archaic vocabulary, emerge as abstracted embodiments of the formative figures: the imperious, chauvinistic father, the devoted, caring mother, the authoritarian governess, and the alienated siblings. Bourgeois covers the surface of the sheet with egg-shaped, proliferating bulges, which develop optionally into petals, breasts or scrotums, as well as with clouds, waves, eyes, vaginas, trees, circles, ellipses, spirals. In Pole fleuri (1950), a rod pierces three forms whose modification, with a few lines, results respectively in a vulva, a mouth, and an eye.

It is not without a self-mocking, mischievous note that Bourgeois repeats the painful role structure through recurrent basic forms. Such a repetitive accumulation goes hand-in-hand with Bourgeois’s desire to repair the past, so that she compares her drawing activity to the restoration of historic tapestries in the parental workshop. ‘Fortunately, my family background was one of repairing damaged tapestries, and the idea of repair has remained with me. Things can be repaired. I have some faith in symbolic actions.’ The dense weave of Bourgeois’s drawings consists of intuitive expressions of emotion and reflects the intimate iconicity of the forms, as well as the emotional intensity of the processed content.

Louise Bourgeois’s earliest striking charcoal and ink works date back to 1947, the heyday of her graphic work, which developed dynamically between painting and sculpture, in other words at the interface between surface and depth. The block-like forms, looking as if carved in stone, correspond with the contemporaneous vertical, statuesque stelae of the Personnages group of sculptures, and can be seen as representations of people who were close to her but no longer by her side after she left her French homeland for America.

The jagged lines and energetic hatchings of other works produced at this time also relate to the rugged cliffs and steep slopes of the landscape in the Creuse region of central France, where Bourgeois grew up. The artist described the harsh mountain region as ‘abandoned and sterile’. After the black, sharply contoured forms of the late 1940s and early 1950s, Bourgeois turned, with increasing fluency in her stroke – now using thin watercolour ranging from delicate tones to bright red – to a soft anthropomorphic landscape in which the resolution is the form-giving element. In this process, mountains turn into breasts and trees into phallic pillars, while the boundaries between human form, mountains and plants become fluid. In the late drawings by the then 96-year-old artist in 2007, forms appear to take on a life of their own and to multiply, female and male features permeate each other in a creative dynamism of mutations and metamorphoses, so that any clear categorization becomes obsolete. The variety of polymorphic manifestations reveals at the same time the complexity of the artist’s psychology, characterized by the turbulent circumstances of her life.

For Louise Bourgeois, the ‘artwork is a language’ whose origin is to be found in mental states. The artist considered the drawing an immediate method of recording psychological realities and expressions of the subconscious. Like the spontaneous, unfiltered écriture automatique of the Surrealists, the pen functions as an instrument for rediscovering memories, as a seismograph of the soul. Personal experiences are symbolically condensed and achieve pictorial expression. Thus, in Bourgeois’s work, forms appear as powerful signs of a highly subjective reality, as primal elements of emotion.

Louise Bourgeois’s source of inspiration always lay in her past. In particular, childhood experiences and memories of her childhood home were the starting point for a groundbreaking fantasy. ‘The creative impulse for all my work is to be found in my childhood.’ The intensity of the emotional content had its roots in the unstable family configuration of father, mother and governess, who was also the father’s lover. The pictorial worlds of the artist, whose primary motivation was always self-representation in the sense of the visualization of a personal, albeit fragile, self-image, revolve again and again around this love triangle and the resulting emotional entanglements.

Her motifs, like an archaic vocabulary, emerge as abstracted embodiments of the formative figures: the imperious, chauvinistic father, the devoted, caring mother, the authoritarian governess, and the alienated siblings. Bourgeois covers the surface of the sheet with egg-shaped, proliferating bulges, which develop optionally into petals, breasts or scrotums, as well as with clouds, waves, eyes, vaginas, trees, circles, ellipses, spirals. In Pole fleuri (1950), a rod pierces three forms whose modification, with a few lines, results respectively in a vulva, a mouth, and an eye.

It is not without a self-mocking, mischievous note that Bourgeois repeats the painful role structure through recurrent basic forms. Such a repetitive accumulation goes hand-in-hand with Bourgeois’s desire to repair the past, so that she compares her drawing activity to the restoration of historic tapestries in the parental workshop. ‘Fortunately, my family background was one of repairing damaged tapestries, and the idea of repair has remained with me. Things can be repaired. I have some faith in symbolic actions.’ The dense weave of Bourgeois’s drawings consists of intuitive expressions of emotion and reflects the intimate iconicity of the forms, as well as the emotional intensity of the processed content.