Dan Peterman

10 Sep - 22 Oct 2011

DAN PETERMAN

La Plage (Plastic Bones)

10 September – 22 October, 2011

Gallery Klosterfelde is pleased to present La Plage (Plastic Bones) , a site-specific installation by Dan Peterman.

„If one member does not fit perfectly the adverse effect will multiply. If, however, every part fits well, the precarious construction will enjoy an astonishing resilience. Life is tight in modular systems“. (Lothar Ledderrose, Ten Thousand Things: Module and Mass Production in Chinese Art . Princeton University Press 2000)

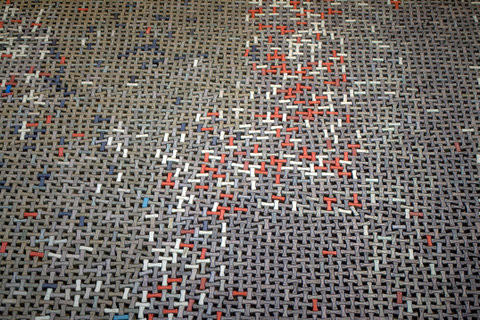

Plastic bones are the basic elements of this exhibition. Each one is similar to the next, but subtly varied in form and color. Each one is palm-sized, smooth, and rounded over; resonating with the hand-feel of tools, toys, and technology. These plastic units are cut from reprocessed post-consumer plastic, and with close examination reveal the randomness by which this material was collected, granulated, melted, extruded and machined into new composite form. They fit to each other like small paving stones.

This network of plastic bones is a unified material system; granules of matter that through particular forces of time and motion have arrived—like a beach—at an optimized form and pattern of alignment. They never find exactly the same configuration twice. Also like a beach, this installation invites play. As the ordered placement of bones in this ends, a space for play and exploration opens up. A point of engagement for kids and others not overly invested in codes of polite contemplation but inclined toward other levels of engagement. "Sous les pavés, la plage" the brilliant slogan of the Situationists from 60's Paris. The beach—that adventurous play space—was (and remains) accessible to those looking beyond the systematic and seemingly secure surface of things.

The bones are simultaneously a modular building system, a toy, and a stockpile of petrochemical molecules that weave into a fabric as limitless as the appetite of our consumer culture. The bits of plastic, compiled here are traces of our endless desire for new commercial offerings: shapes, colors, surfaces and functions. They are the same plastic bits that wash up on all the world's beaches and that slowly churn and accumulate in ocean gyres the size of small countries. They are a super abundant waste product that moves expansively beyond its place in tight modular systems, far beyond what Roland Barthes could have observed when he wrote about it in the 1950's. Nevertheless he succinctly captured its mobile, transformative essence:

"More than a substance" says Barthes, "plastic is the very idea of its infinite transformation; as its everyday name indicates, it is ubiquity made visible. And it is this, in fact, which makes it a miraculous substance: a miracle is always a sudden transformation of nature. Plastic remains impregnated throughout with this wonder: it is less a thing than the trace of a movement." (Roland Barthes, Mythologies , Editions du Seuil, Paris 1957, translation: Jonathan Cape, Hill and Wang, NY 1972)

The exhibition continues at Helga Maria Klosterfelde Edition, Potsdamer Strasse 97, with The Granary (Series) :

The form and scale of these granaries mimic ceramic models from the Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD). These ceramic models were known as ‚mingqi’ and were originally produced as funerary items intended for the dead to use in the afterlife. Mingqi translates roughly into ‚spirit objects’. They depicted objects used in daily life like stoves, latrines, houses and agricultural buildings. Granaries figured prominently among them as they "guaranteed continued affluence for the deceased in the afterlife." 1

Two thousand years later, these miniature granaries provoke questions related to contemporary food production systems and food security. We live at a time of increased ecological instability and severe challenges to our ability to sustainably feed a global human population of nearly seven billion. We also live in an age defined by our dependance on petroleum and at an historically significant moment of ‚peak oil,’ where diminishing discoveries of new petroleum sources, and severe consequences of excessive atmospheric carbon emissions pressure us toward new technologies and new strategies for meeting basic needs. It is a compelling moment to contemplate our transition to post-petroleum living and a compelling moment to consider our strategies for feeding everyone who continues to show up at the dinner table.

The Han period is known for innovative modular production methods—ceramic production included. This granary series however, while borrowing from these modular methods, is made of post-consumer plastics. The color variation comes from the random mixing of plastics during its re-manufacture. While following a repeated production template, each granary—as with Han production—is unique in detail. Additionally, much of this plastic is twice recycled having been previously used in a public sculpture Ground Cover , also by Peterman, that continues to function as an open-air public dancefloor in Chicago. Replaced plastic floor boards showing signs of excessive wear—many having been danced upon for 15 years—serve as primary material stock for producing these granaries. This plastic material, recognizable in many of Peterman's projects, serves as a petro-chemical marker of the peak oil moment we are living in. As with all plastics these objects are capable of spanning centuries, and being unearthed, like ceramic, bronze and stone artifacts, thousands of years in the future—carrying with them a resonant link between a long gone agrarian culture and our current ecological dilemmas.

(1) Quinghua Guo, The Mingqi Pottery Buildings of Han Dynasty China 206 BC - 220 AD , Sussex Academic Press 2010)

Text by Dan Peterman

La Plage (Plastic Bones)

10 September – 22 October, 2011

Gallery Klosterfelde is pleased to present La Plage (Plastic Bones) , a site-specific installation by Dan Peterman.

„If one member does not fit perfectly the adverse effect will multiply. If, however, every part fits well, the precarious construction will enjoy an astonishing resilience. Life is tight in modular systems“. (Lothar Ledderrose, Ten Thousand Things: Module and Mass Production in Chinese Art . Princeton University Press 2000)

Plastic bones are the basic elements of this exhibition. Each one is similar to the next, but subtly varied in form and color. Each one is palm-sized, smooth, and rounded over; resonating with the hand-feel of tools, toys, and technology. These plastic units are cut from reprocessed post-consumer plastic, and with close examination reveal the randomness by which this material was collected, granulated, melted, extruded and machined into new composite form. They fit to each other like small paving stones.

This network of plastic bones is a unified material system; granules of matter that through particular forces of time and motion have arrived—like a beach—at an optimized form and pattern of alignment. They never find exactly the same configuration twice. Also like a beach, this installation invites play. As the ordered placement of bones in this ends, a space for play and exploration opens up. A point of engagement for kids and others not overly invested in codes of polite contemplation but inclined toward other levels of engagement. "Sous les pavés, la plage" the brilliant slogan of the Situationists from 60's Paris. The beach—that adventurous play space—was (and remains) accessible to those looking beyond the systematic and seemingly secure surface of things.

The bones are simultaneously a modular building system, a toy, and a stockpile of petrochemical molecules that weave into a fabric as limitless as the appetite of our consumer culture. The bits of plastic, compiled here are traces of our endless desire for new commercial offerings: shapes, colors, surfaces and functions. They are the same plastic bits that wash up on all the world's beaches and that slowly churn and accumulate in ocean gyres the size of small countries. They are a super abundant waste product that moves expansively beyond its place in tight modular systems, far beyond what Roland Barthes could have observed when he wrote about it in the 1950's. Nevertheless he succinctly captured its mobile, transformative essence:

"More than a substance" says Barthes, "plastic is the very idea of its infinite transformation; as its everyday name indicates, it is ubiquity made visible. And it is this, in fact, which makes it a miraculous substance: a miracle is always a sudden transformation of nature. Plastic remains impregnated throughout with this wonder: it is less a thing than the trace of a movement." (Roland Barthes, Mythologies , Editions du Seuil, Paris 1957, translation: Jonathan Cape, Hill and Wang, NY 1972)

The exhibition continues at Helga Maria Klosterfelde Edition, Potsdamer Strasse 97, with The Granary (Series) :

The form and scale of these granaries mimic ceramic models from the Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD). These ceramic models were known as ‚mingqi’ and were originally produced as funerary items intended for the dead to use in the afterlife. Mingqi translates roughly into ‚spirit objects’. They depicted objects used in daily life like stoves, latrines, houses and agricultural buildings. Granaries figured prominently among them as they "guaranteed continued affluence for the deceased in the afterlife." 1

Two thousand years later, these miniature granaries provoke questions related to contemporary food production systems and food security. We live at a time of increased ecological instability and severe challenges to our ability to sustainably feed a global human population of nearly seven billion. We also live in an age defined by our dependance on petroleum and at an historically significant moment of ‚peak oil,’ where diminishing discoveries of new petroleum sources, and severe consequences of excessive atmospheric carbon emissions pressure us toward new technologies and new strategies for meeting basic needs. It is a compelling moment to contemplate our transition to post-petroleum living and a compelling moment to consider our strategies for feeding everyone who continues to show up at the dinner table.

The Han period is known for innovative modular production methods—ceramic production included. This granary series however, while borrowing from these modular methods, is made of post-consumer plastics. The color variation comes from the random mixing of plastics during its re-manufacture. While following a repeated production template, each granary—as with Han production—is unique in detail. Additionally, much of this plastic is twice recycled having been previously used in a public sculpture Ground Cover , also by Peterman, that continues to function as an open-air public dancefloor in Chicago. Replaced plastic floor boards showing signs of excessive wear—many having been danced upon for 15 years—serve as primary material stock for producing these granaries. This plastic material, recognizable in many of Peterman's projects, serves as a petro-chemical marker of the peak oil moment we are living in. As with all plastics these objects are capable of spanning centuries, and being unearthed, like ceramic, bronze and stone artifacts, thousands of years in the future—carrying with them a resonant link between a long gone agrarian culture and our current ecological dilemmas.

(1) Quinghua Guo, The Mingqi Pottery Buildings of Han Dynasty China 206 BC - 220 AD , Sussex Academic Press 2010)

Text by Dan Peterman