Dunja Herzog

Meanwhile

05 Sep - 18 Oct 2020

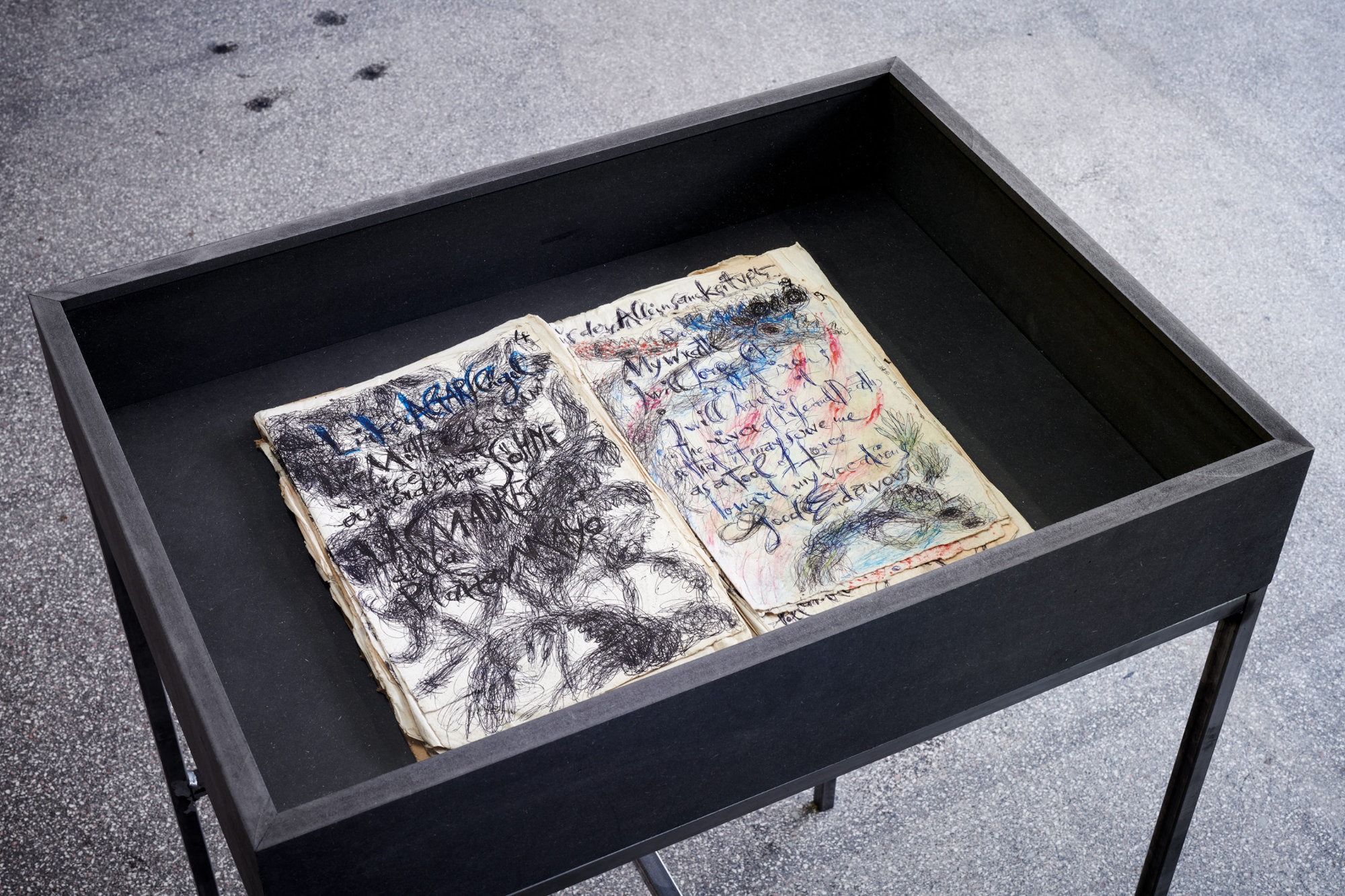

Dunja Herzog: Meanwhile, 2020. Installation view Kölnischer Kunstverein. Courtesy: Dunja Herzog. Photo: Mareike Tocha.

Dunja Herzog: Meanwhile, 2020. Installation view Kölnischer Kunstverein. Courtesy: Dunja Herzog. Photo: Mareike Tocha.

Dunja Herzog: Meanwhile, 2020. Installation view Kölnischer Kunstverein. Courtesy: Dunja Herzog. Photo: Mareike Tocha.

Dunja Herzog: Meanwhile, 2020. Installation view Kölnischer Kunstverein. Courtesy: Dunja Herzog. Photo: Mareike Tocha.

Dunja Herzog: Meanwhile, 2020. Installation view Kölnischer Kunstverein. Courtesy: Dunja Herzog. Photo: Mareike Tocha.

Dunja Herzog: Meanwhile, 2020. Installation view Kölnischer Kunstverein. Courtesy: Dunja Herzog. Photo: Mareike Tocha.

Dunja Herzog: Meanwhile, 2020. Installation view Kölnischer Kunstverein. Courtesy: Dunja Herzog. Photo: Mareike Tocha.

Dunja Herzog: Meanwhile, 2020. Installation view Kölnischer Kunstverein. Courtesy: Dunja Herzog. Photo: Mareike Tocha.

Dunja Herzog: Army of Frogs, 2018 – 2020. Installation view Kölnischer Kunstverein. Courtesy: Dunja Herzog. Photo: Mareike Tocha.

Dunja Herzog: Meanwhile, 2020. Installation view Kölnischer Kunstverein. Courtesy: Dunja Herzog. Photo: Mareike Tocha.

With the solo exhibition Meanwhile by Dunja Herzog, the Kölnischer Kunstverein is realizing a comprehensive exhibition of the artist’s work, accompanied by a program of film screenings, artist talks, performance, children’s workshop and a guided tour of the Cologne-based Women’s History Society. Various elements and themes of different temporalities and backgrounds are brought together in a site-specific installation in which they coexist and relate to one another.

The exhibition is a continuation of the examination of the history of the copper trade, as it is dealt with by the artist in particular in the project Red Gold and its focus on the omnipresent systematic exploitation of the global capitalist project, furthering the investigation with new work produced for the exhibition. In doing so, she looks back to the more distant past: to the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Age, to the history of witch-hunting and copper production in Europe (e.g. by reproducing a 16th century woodcut by Georg Agricola depicting mines for copper mining, as well as a witches’ dance on the Blocksberg in the Harz Mountains). Alongside these are references to mechanisms of commercial profit in order to visualize today’s globally operating economic systems, and considerations of the role of women and reproduction in the transition to capitalism. Her personal background as a Swiss woman is essential in this context. Women’s voting rights in Switzerland, one of the last European countries to institute such rights, only became effective in 1971 (in the canton of Appenzell even only from 1990); another aspect is Switzerland’s role in the system of imperial exploitation.

Not least of all, the material copper is one of the most important global economic indicators with its main trading center in Switzerland since 2011; the five largest Swiss companies are active in raw materials trading. In a new video work by the artist, a geographic and temporal arc is drawn from the Copperbelt in Zambia (a region with the most important copper mining area in Africa, where the Swiss company Glencore also operates mines) to a copper mine in the Harz Mountains, where the largest copper deposit in Germany once existed. At a depth of 165 meters, a film has been produced in Harz, showing the ceiling of a tunnel illuminated by light whilst driving out of the mine—a retreat from the mine and the overexploitation of both nature and labor that was once practiced there. For the artist, questions of resources, mining, exploitation and trade are central: How did it come about that cultural history in Europe transitioned from a reverence for nature, to its exploitation, and then, in the “logic of exploitation”, was exported from Europe to the whole world?

A world where violence, foreign domination and profit prevail and our relationship to the earth, or how it is used and abused, is seen by the artist as synonymous with how bodies and their emotional “landscapes” are dealt with. The more resources, including copper—without which our contemporary digital world is inconceivable—are mined, the more the search for or connection to inner resources seems relevant.

These various themes and their associated stories, which almost always speak of violence, are not necessarily addressed directly in the exhibition or reproduced. Rather, they are kept present through the materials enlisted, by relating to their origin, their use, their historical relevance, their development and the trade routes that have shaped our society very physically over time. Thus, for the exhibition, baskets made of copper wire from electronic scrap have been created in collaboration with basket makers from the Republic of Benin in Lagos, a city that belongs to one of the largest electronic dumping sites in West Africa; not only to detach the material from one value chain and transpose it into another, but to simultaneously pay homage to the women of Nigeria and Zambia, who made significant contributions to the independence of both countries. These colonial legacies seem particularly relevant to the building of the Kölnischer Kunstverein itself, since it was the seat of the British Council – the so called “Die Brücke” (The Bridge)—in the enduring colonial period of the British, and its proposition of a “bridge” to the world after the Second World War.

The artist creates a space, in a certain sense a “third space”, in which a larger spectrum of stories and their complex interrelations with matter, material and their transformation and relationship to people can be experienced, and other perspectives made possible. From the materials and plants that are addressed, she extracts, in a way, the essence of their inherent energies and logics, makes them physically perceptible and thus ultimately also calls upon their nourishing properties.

The two editions Sea field and Death of Nature will be published on the occasion of this exhibition.

Dunja Herzog (*1976 in Basel, Switzerland) lived last year in Lagos, Nigeria, where she created some of the work presented at the Kölnischer Kunstverein. Her works were shown at the Kunstverein Göttingen; Swiss Art Awards, Basel (both 2018); Lagos Biennale, Lagos, Nigeria (2017); BLOK art space, Istanbul; 1646, Den Haag (all 2016); New Bretagne / Belle Air, Essen and at MAXXI Museum, Rome (both 2015), among others.

Curator: Nikola Dietrich

The exhibition is a continuation of the examination of the history of the copper trade, as it is dealt with by the artist in particular in the project Red Gold and its focus on the omnipresent systematic exploitation of the global capitalist project, furthering the investigation with new work produced for the exhibition. In doing so, she looks back to the more distant past: to the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Age, to the history of witch-hunting and copper production in Europe (e.g. by reproducing a 16th century woodcut by Georg Agricola depicting mines for copper mining, as well as a witches’ dance on the Blocksberg in the Harz Mountains). Alongside these are references to mechanisms of commercial profit in order to visualize today’s globally operating economic systems, and considerations of the role of women and reproduction in the transition to capitalism. Her personal background as a Swiss woman is essential in this context. Women’s voting rights in Switzerland, one of the last European countries to institute such rights, only became effective in 1971 (in the canton of Appenzell even only from 1990); another aspect is Switzerland’s role in the system of imperial exploitation.

Not least of all, the material copper is one of the most important global economic indicators with its main trading center in Switzerland since 2011; the five largest Swiss companies are active in raw materials trading. In a new video work by the artist, a geographic and temporal arc is drawn from the Copperbelt in Zambia (a region with the most important copper mining area in Africa, where the Swiss company Glencore also operates mines) to a copper mine in the Harz Mountains, where the largest copper deposit in Germany once existed. At a depth of 165 meters, a film has been produced in Harz, showing the ceiling of a tunnel illuminated by light whilst driving out of the mine—a retreat from the mine and the overexploitation of both nature and labor that was once practiced there. For the artist, questions of resources, mining, exploitation and trade are central: How did it come about that cultural history in Europe transitioned from a reverence for nature, to its exploitation, and then, in the “logic of exploitation”, was exported from Europe to the whole world?

A world where violence, foreign domination and profit prevail and our relationship to the earth, or how it is used and abused, is seen by the artist as synonymous with how bodies and their emotional “landscapes” are dealt with. The more resources, including copper—without which our contemporary digital world is inconceivable—are mined, the more the search for or connection to inner resources seems relevant.

These various themes and their associated stories, which almost always speak of violence, are not necessarily addressed directly in the exhibition or reproduced. Rather, they are kept present through the materials enlisted, by relating to their origin, their use, their historical relevance, their development and the trade routes that have shaped our society very physically over time. Thus, for the exhibition, baskets made of copper wire from electronic scrap have been created in collaboration with basket makers from the Republic of Benin in Lagos, a city that belongs to one of the largest electronic dumping sites in West Africa; not only to detach the material from one value chain and transpose it into another, but to simultaneously pay homage to the women of Nigeria and Zambia, who made significant contributions to the independence of both countries. These colonial legacies seem particularly relevant to the building of the Kölnischer Kunstverein itself, since it was the seat of the British Council – the so called “Die Brücke” (The Bridge)—in the enduring colonial period of the British, and its proposition of a “bridge” to the world after the Second World War.

The artist creates a space, in a certain sense a “third space”, in which a larger spectrum of stories and their complex interrelations with matter, material and their transformation and relationship to people can be experienced, and other perspectives made possible. From the materials and plants that are addressed, she extracts, in a way, the essence of their inherent energies and logics, makes them physically perceptible and thus ultimately also calls upon their nourishing properties.

The two editions Sea field and Death of Nature will be published on the occasion of this exhibition.

Dunja Herzog (*1976 in Basel, Switzerland) lived last year in Lagos, Nigeria, where she created some of the work presented at the Kölnischer Kunstverein. Her works were shown at the Kunstverein Göttingen; Swiss Art Awards, Basel (both 2018); Lagos Biennale, Lagos, Nigeria (2017); BLOK art space, Istanbul; 1646, Den Haag (all 2016); New Bretagne / Belle Air, Essen and at MAXXI Museum, Rome (both 2015), among others.

Curator: Nikola Dietrich