Udo is Love

Time Is Sin – A Journey into the Extraordinary Life of Udo Kier

27 Sep - 18 Dec 2024

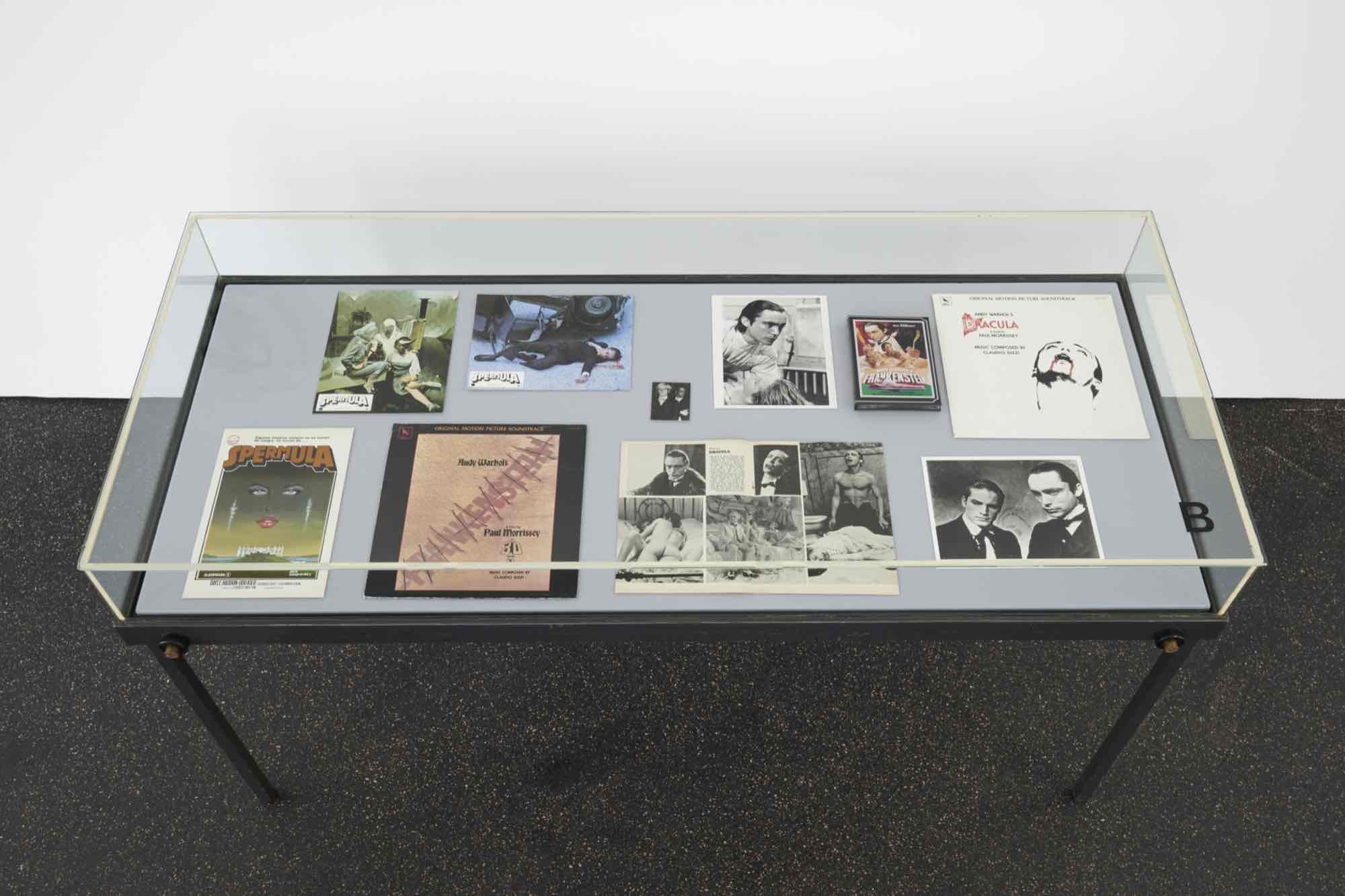

Installation view Udo is Love. Time is the sin – A journey into the incredible life of Udo Kier. Kölnischer Kunstverein 2024. Photo: Mareike Tocha

Installation view Udo is Love. Time is the sin – A journey into the incredible life of Udo Kier. Kölnischer Kunstverein 2024. Photo: Mareike Tocha

Installation view Udo is Love. Time is the sin – A journey into the incredible life of Udo Kier. Kölnischer Kunstverein 2024. Photo: Mareike Tocha

Installation view Udo is Love. Time is the sin – A journey into the incredible life of Udo Kier. Kölnischer Kunstverein 2024. Photo: Mareike Tocha

Installation view Udo is Love. Time is the sin – A journey into the incredible life of Udo Kier. Kölnischer Kunstverein 2024. Photo: Mareike Tocha

Udo Kier was born in Cologne’s district of Lindenthal on 14 October 1944. That evening, the nurse placed all the children in the maternity ward on a table, ready to be washed. Udo’s mother asked if she could hold her son in her arms a little while longer. When the bomb struck, she was able to cover him with one hand and hold back the collapsing wall with the other. None of the other newborns survived; only the two of them were dug out of the rubble of the delivery room alive. During operation Hurricane, more bombs were dropped on the Rheinland in the space of twenty-four hours than on any other day of the Second World War.

Udo grew up in the city’s district of Mülheim. In the morning, he would fold away his wall bed and walk to school over rubble. The evening meal alternated between lentil and potato soup. On Sundays, they had a piece of meat with a green salad and pudding. After dinner he would be given fifty pfennigs and go to the cinema. His favourite film was Suddenly, Last Summer with Elizabeth Taylor. To please his mother, he began an apprenticeship at a tool wholesaler in the nearby district of Kalk. By his early twenties he’d become a qualified salesman, and travelled to London in order to learn English. He was hoping to become something like the foreign business representative for the German pharmaceutical company Bayer. He’d earned the money for the journey by working on the production line at Ford. London offered opportunities that Cologne never could. Several unknown men invited him for a glass of champagne in a nightclub. They introduced themselves as Visconti, Nureyev and Berger. Kier knew from shaving in the mirror every morning that he looked incredible. In London he discovered his good fortune of being in the right place at the right time. The singer and producer Michael Sarne gave him the part of the gigolo in Road to San Tropez (1966). Beneath the camera’s gaze, the man with the green eyes was reborn, and no one would forget them. Following his first short film, “the new face of cinema” was still searching confusedly for the camera while peopled hailed him as a star. For the directors who hired him, “the most handsome boy in the world” embodied the face of evil. In Schamlos (Shameless, 1968), his first feature length film, he played a ruthless pimp. Courting scandal, the film dramatically exposed the reality of Vienna’s underworld. In Mark of the Devil (1969), he played one of the most vicious torturers in the history of film; it was followed by the role of a killer in The Salzburg Connection (1972). The films are grim, and most are rarely shown, but they shaped Kier’s future image. It was another three years before he became a figure of glamour, but his proclivity for sinister parts persisted: he won the leading role in Andy Warhol’s Flesh for Frankenstein (1973) and followed it up with the funniest ever Dracula (1974) in the history of film. In Paris and New York he was now considered “hot”. His role as the angelic libertine in Story of O (1975) became his cinematic breakthrough. Embracing life, he set sail upon a sea of opportunities like a sombre spirit. At the same time, his inquisitive mind refused to be pinned down. He moved capriciously from horror to opulently produced erotic films like Spermula (1976), to the coldly clinical realism of Rainer Werner Fassbinder. All this time, he remained true to himself by becoming something that, since the end of the Third Reich, Germans were no longer allowed to be: Kier was dangerous. He prowled the edges of the abyss like a beast of prey, in search of those brave enough to take risks. Though too unruly for any authority, at times his languid passion would loiter timidly in corners, as if it found even itself creepy.

Kier worked with Werner Schroeter on Goldflocken (Goldflakes, 1976), and with Robert von Ackeren on Belcanto oder Darf eine Nutte schluchzen? (Bel Canto, or May a Hooker Sob? 1977) and Victor (1978, by Walter Bockmayer) – insane films that transposed the American concept of camp into German cinema. Always utterly present and somewhat detached, he never found a lasting home for himself. In the “families” of directors like Warhol or Fassbinder he remained a loner, who eventually left. He was driven, someone who invented himself, and yet he could not live without the gaze of others. In his constant criss-crossing between trash, experimental and auteur films, Kier assumed a perplexing variety of different masks. As a result, he became a unique figure, one whose style was both moving and unsettling. Lars von Trier – a key encounter – cautioned him ”don’t act”; but even before this, his acting made audiences feel Hahnenstraße 6, 50667 Köln, Telefon +49 (221) 21 70 21 info@koelnischerkunstverein.de like he wasn’t acting. His was a technique that aimed more at affecting others than expressing himself.

Kier leapt elegantly between CinemaScope and Super 8, as if high and low were twisted bands of elastic in a game of Chinese jump rope. One moment he was stroking enraptured his tortoise’s neck, the next he was driven by an urge to provoke a state of emergency. A determination to wring everything he could from life went hand in hand with a gift for improvisation. Directors loved the way he made scenes his own and reinvented them in ways they had never intended. A dandy who created images of himself that weren’t in the script, but which nevertheless burned themselves into audiences’ memories.

In the year of German reunification, Kier again found a way of inscribing himself upon the spirit of the moment. In Die letzte Stunde im Führerbunker (The Last Hour in the Führerbunker, 1989), directed by Christoph Schlingensief, he took on a role that he would go on to play many times – that of Adolf Hitler. Shot in a single night, the film gives the impression of its traumatic events being imbued by a monstrous group therapy. Following this cinematic nightmare, Kier left Europe. Gus Van Sant brought him to America. Once again a new chapter began. In Gus Van Sant’s My Own Private Idaho (1991), Kier as Hans grabs the hotel room’s table lamp to perform his song Der Adler (The Eagle, 1985), and his rendition puts his handsome young coactors in the shade. In America, the German with the strong accent almost acquired qualities of a character from a comic book. He appeared in such films as Barb Wire (1996) with Pamela Anderson, and Johnny Mnemonic (1999) by the artist Robert Longo; or he played the decadent husband who recites Goethe’s Faust by Madonna’s side, before the two of them enter a sex club. During these years, Kier honed his mastery at helping others to turn in great performances. And he managed effortlessly to keep pace with the times. The latest future of this comedian of the sinister is beginning right now, as he appears alongside Hunter Schäfer in the computer game OD (2025) by Hideo Kojima.

The exhibition Udo is Love makes no claim to show Kier in all his complexity. It focusses upon his many different appearances in the visual arts, some of them known only through anecdote. One of these involvements began in 1968, when the Viennese Actionist Otto Mühl staged one of his “material actions” in the feature film Schamlos. His collaboration with Warhol in the early seventies granted him admission to the school of the beautiful apparition that destroys itself. Back in Cologne, the artist Michael Buthe several times cast Kier as a prince. In 1977 Sigmar Polke, who had followed Kier around with his Bolex, designed together with Mariette Althaus a piece of neon lettering, a present that quickly fell off the wall, to which this exhibition owes its title: Udo is Love. The first generation of video artists, from Marcel Odenbach to Gábor Bódy, were inspired by the non-artificial artificiality of the extra-terrestrial from Cologne-Ostheim. Rosemarie Trockel explored with Kier the perspectives of protest.

The occasion for this overview of Kier’s long career is not only his eightieth birthday. Kier’s approach as an artist remains state-of-the-art, full of possibilities for engaging with a reality that we would often rather just escape. If the world is going to fall apart tomorrow, why not shape it into fantastic counter-realities today. Kier sees the challenges of a collapsing reality as an invitation to throw it further into confusion. It seems to matter little to him whether anyone likes the poses he adopts in pursuit of this; his main concern is not to be boring. His need to be the centre of attention is also a search for what cannot exist. It does not satisfy itself, but rather is part of a long, interminable movement around an empty centre – a dance without a name, which can never be danced alone.

Curated by Hans-Christian Dany and Valérie Knoll

Udo grew up in the city’s district of Mülheim. In the morning, he would fold away his wall bed and walk to school over rubble. The evening meal alternated between lentil and potato soup. On Sundays, they had a piece of meat with a green salad and pudding. After dinner he would be given fifty pfennigs and go to the cinema. His favourite film was Suddenly, Last Summer with Elizabeth Taylor. To please his mother, he began an apprenticeship at a tool wholesaler in the nearby district of Kalk. By his early twenties he’d become a qualified salesman, and travelled to London in order to learn English. He was hoping to become something like the foreign business representative for the German pharmaceutical company Bayer. He’d earned the money for the journey by working on the production line at Ford. London offered opportunities that Cologne never could. Several unknown men invited him for a glass of champagne in a nightclub. They introduced themselves as Visconti, Nureyev and Berger. Kier knew from shaving in the mirror every morning that he looked incredible. In London he discovered his good fortune of being in the right place at the right time. The singer and producer Michael Sarne gave him the part of the gigolo in Road to San Tropez (1966). Beneath the camera’s gaze, the man with the green eyes was reborn, and no one would forget them. Following his first short film, “the new face of cinema” was still searching confusedly for the camera while peopled hailed him as a star. For the directors who hired him, “the most handsome boy in the world” embodied the face of evil. In Schamlos (Shameless, 1968), his first feature length film, he played a ruthless pimp. Courting scandal, the film dramatically exposed the reality of Vienna’s underworld. In Mark of the Devil (1969), he played one of the most vicious torturers in the history of film; it was followed by the role of a killer in The Salzburg Connection (1972). The films are grim, and most are rarely shown, but they shaped Kier’s future image. It was another three years before he became a figure of glamour, but his proclivity for sinister parts persisted: he won the leading role in Andy Warhol’s Flesh for Frankenstein (1973) and followed it up with the funniest ever Dracula (1974) in the history of film. In Paris and New York he was now considered “hot”. His role as the angelic libertine in Story of O (1975) became his cinematic breakthrough. Embracing life, he set sail upon a sea of opportunities like a sombre spirit. At the same time, his inquisitive mind refused to be pinned down. He moved capriciously from horror to opulently produced erotic films like Spermula (1976), to the coldly clinical realism of Rainer Werner Fassbinder. All this time, he remained true to himself by becoming something that, since the end of the Third Reich, Germans were no longer allowed to be: Kier was dangerous. He prowled the edges of the abyss like a beast of prey, in search of those brave enough to take risks. Though too unruly for any authority, at times his languid passion would loiter timidly in corners, as if it found even itself creepy.

Kier worked with Werner Schroeter on Goldflocken (Goldflakes, 1976), and with Robert von Ackeren on Belcanto oder Darf eine Nutte schluchzen? (Bel Canto, or May a Hooker Sob? 1977) and Victor (1978, by Walter Bockmayer) – insane films that transposed the American concept of camp into German cinema. Always utterly present and somewhat detached, he never found a lasting home for himself. In the “families” of directors like Warhol or Fassbinder he remained a loner, who eventually left. He was driven, someone who invented himself, and yet he could not live without the gaze of others. In his constant criss-crossing between trash, experimental and auteur films, Kier assumed a perplexing variety of different masks. As a result, he became a unique figure, one whose style was both moving and unsettling. Lars von Trier – a key encounter – cautioned him ”don’t act”; but even before this, his acting made audiences feel Hahnenstraße 6, 50667 Köln, Telefon +49 (221) 21 70 21 info@koelnischerkunstverein.de like he wasn’t acting. His was a technique that aimed more at affecting others than expressing himself.

Kier leapt elegantly between CinemaScope and Super 8, as if high and low were twisted bands of elastic in a game of Chinese jump rope. One moment he was stroking enraptured his tortoise’s neck, the next he was driven by an urge to provoke a state of emergency. A determination to wring everything he could from life went hand in hand with a gift for improvisation. Directors loved the way he made scenes his own and reinvented them in ways they had never intended. A dandy who created images of himself that weren’t in the script, but which nevertheless burned themselves into audiences’ memories.

In the year of German reunification, Kier again found a way of inscribing himself upon the spirit of the moment. In Die letzte Stunde im Führerbunker (The Last Hour in the Führerbunker, 1989), directed by Christoph Schlingensief, he took on a role that he would go on to play many times – that of Adolf Hitler. Shot in a single night, the film gives the impression of its traumatic events being imbued by a monstrous group therapy. Following this cinematic nightmare, Kier left Europe. Gus Van Sant brought him to America. Once again a new chapter began. In Gus Van Sant’s My Own Private Idaho (1991), Kier as Hans grabs the hotel room’s table lamp to perform his song Der Adler (The Eagle, 1985), and his rendition puts his handsome young coactors in the shade. In America, the German with the strong accent almost acquired qualities of a character from a comic book. He appeared in such films as Barb Wire (1996) with Pamela Anderson, and Johnny Mnemonic (1999) by the artist Robert Longo; or he played the decadent husband who recites Goethe’s Faust by Madonna’s side, before the two of them enter a sex club. During these years, Kier honed his mastery at helping others to turn in great performances. And he managed effortlessly to keep pace with the times. The latest future of this comedian of the sinister is beginning right now, as he appears alongside Hunter Schäfer in the computer game OD (2025) by Hideo Kojima.

The exhibition Udo is Love makes no claim to show Kier in all his complexity. It focusses upon his many different appearances in the visual arts, some of them known only through anecdote. One of these involvements began in 1968, when the Viennese Actionist Otto Mühl staged one of his “material actions” in the feature film Schamlos. His collaboration with Warhol in the early seventies granted him admission to the school of the beautiful apparition that destroys itself. Back in Cologne, the artist Michael Buthe several times cast Kier as a prince. In 1977 Sigmar Polke, who had followed Kier around with his Bolex, designed together with Mariette Althaus a piece of neon lettering, a present that quickly fell off the wall, to which this exhibition owes its title: Udo is Love. The first generation of video artists, from Marcel Odenbach to Gábor Bódy, were inspired by the non-artificial artificiality of the extra-terrestrial from Cologne-Ostheim. Rosemarie Trockel explored with Kier the perspectives of protest.

The occasion for this overview of Kier’s long career is not only his eightieth birthday. Kier’s approach as an artist remains state-of-the-art, full of possibilities for engaging with a reality that we would often rather just escape. If the world is going to fall apart tomorrow, why not shape it into fantastic counter-realities today. Kier sees the challenges of a collapsing reality as an invitation to throw it further into confusion. It seems to matter little to him whether anyone likes the poses he adopts in pursuit of this; his main concern is not to be boring. His need to be the centre of attention is also a search for what cannot exist. It does not satisfy itself, but rather is part of a long, interminable movement around an empty centre – a dance without a name, which can never be danced alone.

Curated by Hans-Christian Dany and Valérie Knoll