P. Staff

In Ekstase

09 Jun - 10 Sep 2023

P. Staff, In Ekstase, Kunsthalle Basel, 2023, exhibition view, photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel

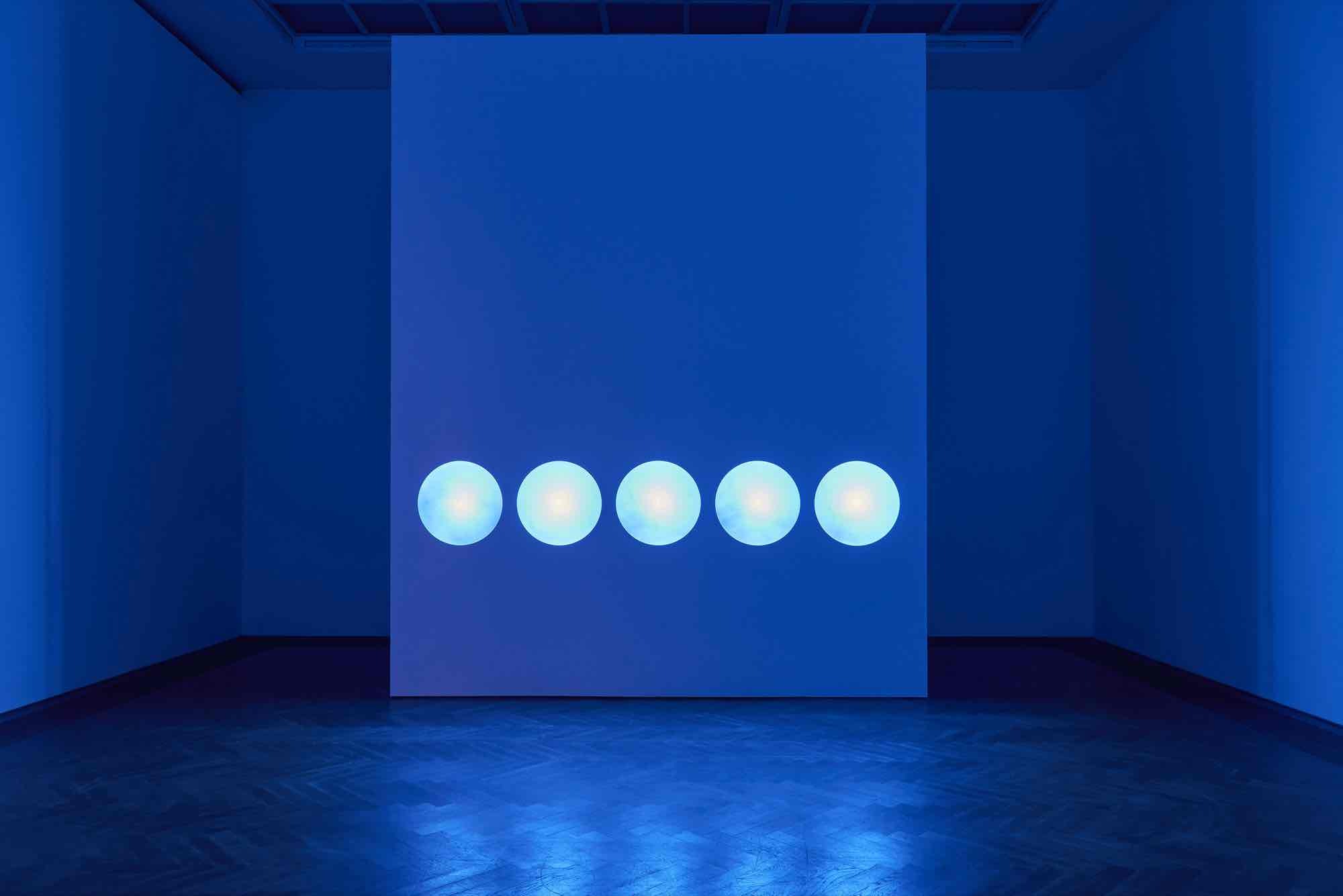

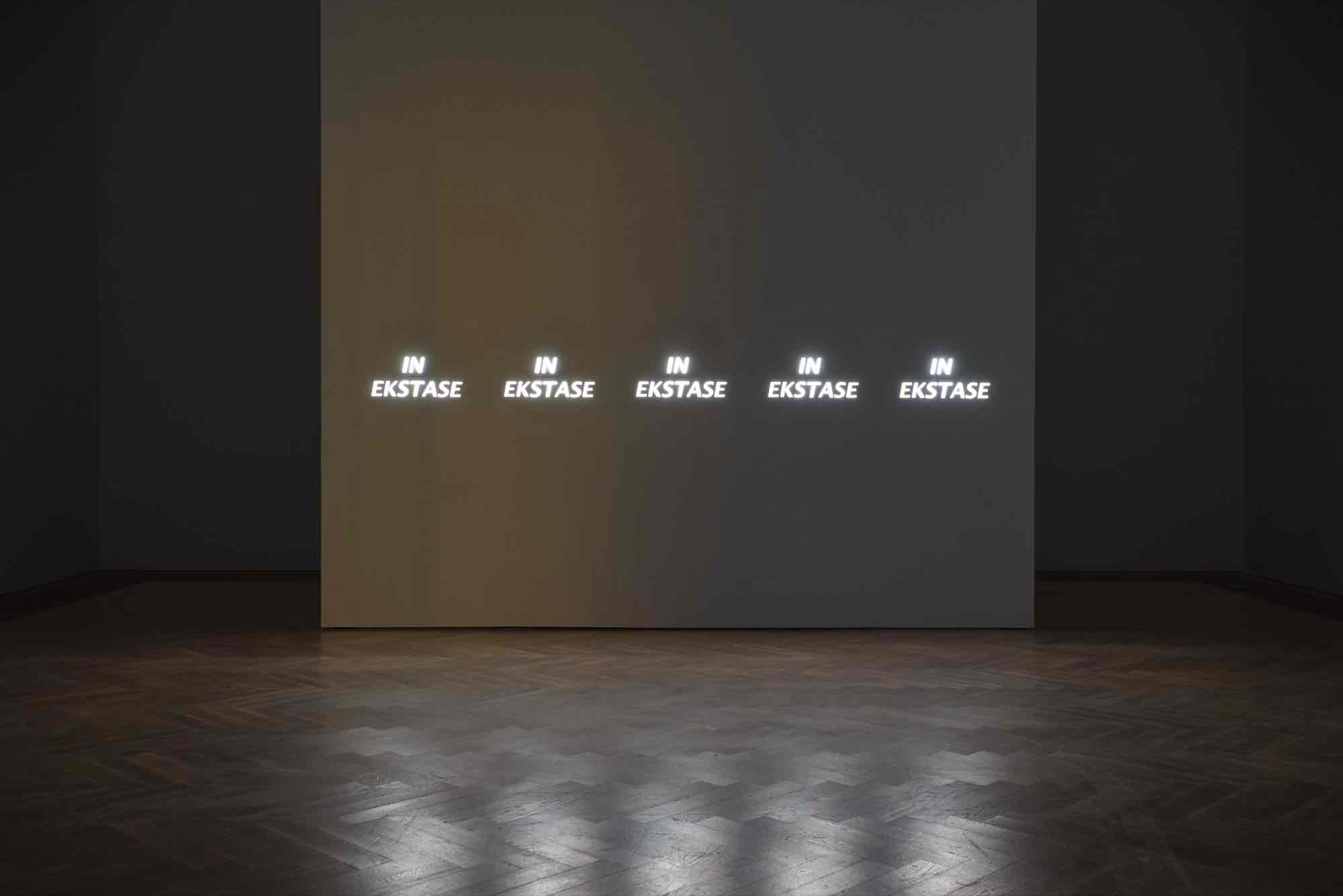

P. Staff, In Ekstase, 2023, installation view, in: P. Staff, In Ekstase, Kunsthalle Basel, 2023, photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel

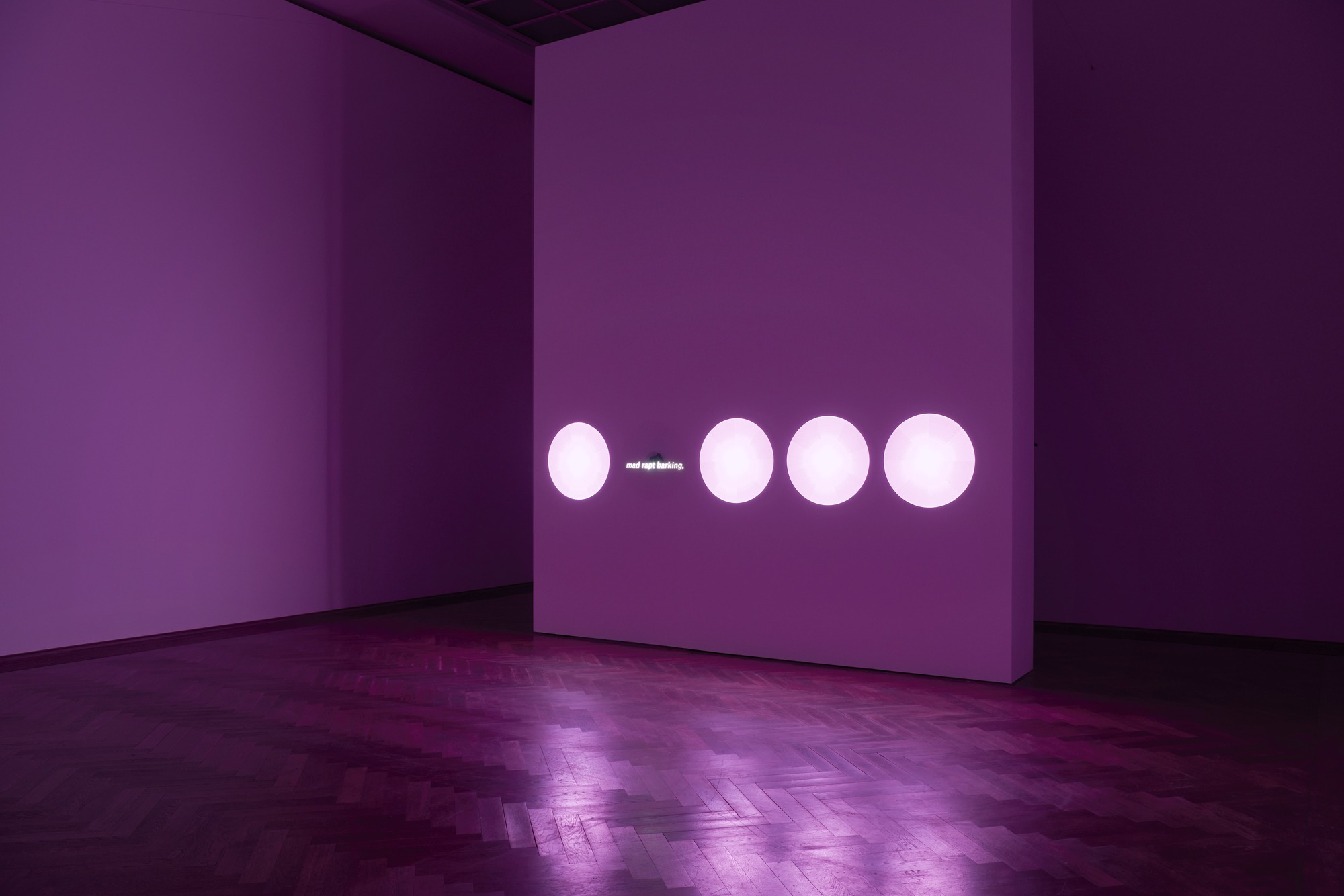

P. Staff, La Nuit Américaine, 2023, installation view, in: P. Staff, In Ekstase, Kunsthalle Basel, 2023,

photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel

photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel

P. Staff, Afferent Nerves, 2023, installation view, in: P. Staff, In Ekstase, Kunsthalle Basel, 2023, photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel

P. Staff, In Ekstase, Kunsthalle Basel, 2023, exhibition view, photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel

P. Staff, In Ekstase, Kunsthalle Basel, 2023, exhibition view, photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel

P. Staff in collaboration with Basse Stittgen, Bloodheads (Kunsthalle Basel), 2023, detail, in: P. Staff, In Ekstase, Kunsthalle Basel, 2023,

photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel

photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel

P. Staff, In Ekstase, Kunsthalle Basel, 2023, exhibition view, photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel

P. Staff, In Ekstase, 2023, installation view, in: P. Staff, In Ekstase, Kunsthalle Basel, 2023, photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel

P. Staff, In Ekstase, 2023, installation view, in: P. Staff, In Ekstase, Kunsthalle Basel, 2023, photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel

A favorable review might call an exhibition “electric.” And this one is. Literally. It pulses with a galvanic charge: an electrical system and network of cords loom above visitors’ heads in the first room, just out of reach. But what if you nevertheless managed to jump up and touch it? The flexible structure’s electrical ele- ments are often deployed to contain livestock; it is intended to prevent the crossing of a boundary, whether motivated by the will to intrude or flee. To be in contact with the limit it circumscribes is to receive a punishing shock. Applying such a system to the upper perimeter of an institutional exhibition space may be a metaphoric gesture, but the danger is real. As you progress through the exhibition rooms, you understand that the atmosphere of menace persists, conceptually and intellectually, if not actually. But, make no mistake, the mood of P. Staff’s exhibition is also rapturous—after all, the show’s title announces an ecstatic state— even as it is a cleaving open of pervasive notions of gender, state-sanctioned violence, and the (mortal) body.

A wallpaper produced from a photograph (a selfportrait of the artist, in fact) spans the entirety of the wall opposite the entrance. Larger than life, awash in indigo, the figure is bedridden, their face covered, an insinuation of suffering or retreat. So blue. It forms the backdrop to that electrified netting whose title, Afferent Nerves, refers to “afferent neurons,” the nerve fibers that bring sensory information from the outside world into the brain, including senses of touch, temperature, and pain. If the title underscores how the work reimagines a fundamental infrastructure of the building—electricity—as a kind of nervous system, we cannot ignore its carceral aspect either: the shock produced is the result of a closed circuit, completed by the flesh of the animal, or human, attempting to cross it.

For the transgender British artist, filmmaker, and poet, decisions about lighting, an electrical spark, or atmosphere are not secondary to the act of making art. They constitute art- works in themselves, alongside the new video and sculptures on view. Together, they draw on recurrent concerns in Staff’s practice, including the processes by which the living— especially minoritarian communities—are disciplined in a society defined by the institu- tionalized violence of our present. The body has always played a fundamental role in under- standing this exertion of power, and accordingly, Staff describes the body as “a flashpoint, a crisis point—for politics, law, intimacy, sensation—a contentious site that I can’t get away from.” Electrifying the (institutional) body, the exhibition announces from its outset the threat and potential harm embedded in institutional logic and frameworks.

An intertwining of affliction and contamina- tion is a related, consistent theme running through Staff’s oeuvre, often signaled through harsh, fluorescent light and color. Here, an acrid yellow that the artist has used in previous installations returns, emitted by the lighting in the first space. The hue is not the yellow of butter or candlelight, honey or gold; it is the yellow of piss, of warning signs announcing radioactivity, of jaundiced skin seen in an all-too-glaring spotlight. Slightly sickly and unsettling, the artist intends for it to soak into you.

Brash hues continue in the second room, radiating with more yellow light filtering in from the windows and red spilling from fluorescent tube lighting. Central to the room is an ostentatious display of familiar-looking objects (door and window handles, flooring panels and skirting, electrical socket covers, locker tags). To look around is to notice that some of these— discernable by their burnt look—have also been installed back into the Kunsthalle’s building. So discrete is their presence, you may not have noticed at first that you passed one such doorhandle as you entered the exhibition from the foyer, or that you walked across panels of blackened floor. These sculptures are in every way the same shape, dimension, and form as the objects they mimick—except that they are cast in animal blood collected from the excessive output of slaughterhouses. In its untreated liquid form, this blood is heated and pressurized to such in tense temperatures that it turns solid, fossilized. Staff’s Bloodheads (Kunsthalle Basel), a collab- oration with industrial designer Basse Stittgen, turn the absolute banality of an institution’s fixtures and architectural details into something uncanny, eerily and brutally corporeal. Animal, human, and institution merge as these undead things now haunt the building.

The third room is a dimly lit cabinet for a series of steel intaglio etchings whose lines of text and images are burned onto a plate through a corrosive wash of acid. Each mirrored plate repro- duces a redacted document, its text differently veiled in each. To look is to encounter the image of yourself reflected on a surface that reprints a standard consent form for human sterilization. Government-mandated or otherwise coerced surgery to remove irreversibly a person’s capacity to reproduce is invariably woven into a history of borders, war, disability, and eugenics. The practice stems from so-called “hygiene laws,” shockingly still in place as late as 1970 in many countries, including Switzerland. It extends to the more recent and widespread requirement for the sterilization of transgender people as a condition for their obtainment of legal gender recognition. Quietly and devastatingly, the etchings insinuate the ways in which the body’s agency and autonomy are officially appropriated and controlled.

The primacy of text carries over into the fourth room, but here it levitates—a product of light, gravity, and grace. The artist’s holographic imagepoem is equal parts lyrical, sculptural, and filmic. In its spectral presence, the work flirts with a long film tradition: it has the material, flickering quality of early cinema or Structuralist films of the 1960s and ‘70s or even of magic lanterns and optical illusions, while being a decidedly con- temporary phantasmagoria. The blades of the holographic fans propel, Staff would tell you, an interrogation of what it is to be living, sensing, delirious, ecstatic, and suffering—in a world on fire. The poem ends with the repeated, halting assertion: “I AM ALIVE” / “YOU ARE DEAD.” Yet the speaker of the statements remains ambiguous: is it the artist addressing themself, the artist addressing the viewer, or the machine addressing the human?

Central to the exhibition’s final installation is Staff’s new film, La Nuit Américaine. Its title refers to the French term for the analog film technique of shooting by day, with a complex set of lenses and filters, to simulate a deep black-blue night. Though used frequently in early Hollywood films, the deception was often compromised, giving away the trick—the sun creeping into the frame, a reflection that wouldn’t occur in the moon’s soft light. Staff uses the technique, but does nothing to hide that it was filmed during the daytime: people play golf, birds sing, shoppers consume, and families gather under sun umbrellas at the beach. The film’s bald duplicity combines with its sense of increasing anxiousness. It seems to ask: What would happen if we lived in an eternal twilight, if time stuttered, and day be- came indistinguishable from night? Trash and nature, animals and humans fill the screen as if assemblies of the living and undead evoked in the previous rooms have come to congregate there. Without words or narration, the film’s juddering soundtrack of ambient noise, laugh- ter, violas, and cellos, at times rendered syn- thetic and strange, accompany a quickening of image rhythm and cuts wherein the quotidian slides into horror or discomfort. As the film flits from darkness and emptiness to density and abstraction, it ends in a crescendo irradi- ating the entire room with an image of glaring sunlight and strobing, syncopated flashes. This ominous societal portrait ends in what the artist hopes will be a kind of ecstatic release. In Ekstase.

It was the Austrian poet and author Ingeborg Bachmann who once wrote: “I am writing with my burnt hand about the nature of fire.” Staff, too, has taken this task to heart. The fires that Staff encounters are the red-hot embers of social and structural violence and ecological disasters that have become our new normal. Staff’s hand may be burnt as they write, film, and build worlds through their art, and yet, unrelentingly, their exhibition invites visitors to step closer to the fire: it burns images on the retina much like those that result from star- ing too long at the blazing ball of fire and gas that is the sun—gorgeous, but it hurts.

A wallpaper produced from a photograph (a selfportrait of the artist, in fact) spans the entirety of the wall opposite the entrance. Larger than life, awash in indigo, the figure is bedridden, their face covered, an insinuation of suffering or retreat. So blue. It forms the backdrop to that electrified netting whose title, Afferent Nerves, refers to “afferent neurons,” the nerve fibers that bring sensory information from the outside world into the brain, including senses of touch, temperature, and pain. If the title underscores how the work reimagines a fundamental infrastructure of the building—electricity—as a kind of nervous system, we cannot ignore its carceral aspect either: the shock produced is the result of a closed circuit, completed by the flesh of the animal, or human, attempting to cross it.

For the transgender British artist, filmmaker, and poet, decisions about lighting, an electrical spark, or atmosphere are not secondary to the act of making art. They constitute art- works in themselves, alongside the new video and sculptures on view. Together, they draw on recurrent concerns in Staff’s practice, including the processes by which the living— especially minoritarian communities—are disciplined in a society defined by the institu- tionalized violence of our present. The body has always played a fundamental role in under- standing this exertion of power, and accordingly, Staff describes the body as “a flashpoint, a crisis point—for politics, law, intimacy, sensation—a contentious site that I can’t get away from.” Electrifying the (institutional) body, the exhibition announces from its outset the threat and potential harm embedded in institutional logic and frameworks.

An intertwining of affliction and contamina- tion is a related, consistent theme running through Staff’s oeuvre, often signaled through harsh, fluorescent light and color. Here, an acrid yellow that the artist has used in previous installations returns, emitted by the lighting in the first space. The hue is not the yellow of butter or candlelight, honey or gold; it is the yellow of piss, of warning signs announcing radioactivity, of jaundiced skin seen in an all-too-glaring spotlight. Slightly sickly and unsettling, the artist intends for it to soak into you.

Brash hues continue in the second room, radiating with more yellow light filtering in from the windows and red spilling from fluorescent tube lighting. Central to the room is an ostentatious display of familiar-looking objects (door and window handles, flooring panels and skirting, electrical socket covers, locker tags). To look around is to notice that some of these— discernable by their burnt look—have also been installed back into the Kunsthalle’s building. So discrete is their presence, you may not have noticed at first that you passed one such doorhandle as you entered the exhibition from the foyer, or that you walked across panels of blackened floor. These sculptures are in every way the same shape, dimension, and form as the objects they mimick—except that they are cast in animal blood collected from the excessive output of slaughterhouses. In its untreated liquid form, this blood is heated and pressurized to such in tense temperatures that it turns solid, fossilized. Staff’s Bloodheads (Kunsthalle Basel), a collab- oration with industrial designer Basse Stittgen, turn the absolute banality of an institution’s fixtures and architectural details into something uncanny, eerily and brutally corporeal. Animal, human, and institution merge as these undead things now haunt the building.

The third room is a dimly lit cabinet for a series of steel intaglio etchings whose lines of text and images are burned onto a plate through a corrosive wash of acid. Each mirrored plate repro- duces a redacted document, its text differently veiled in each. To look is to encounter the image of yourself reflected on a surface that reprints a standard consent form for human sterilization. Government-mandated or otherwise coerced surgery to remove irreversibly a person’s capacity to reproduce is invariably woven into a history of borders, war, disability, and eugenics. The practice stems from so-called “hygiene laws,” shockingly still in place as late as 1970 in many countries, including Switzerland. It extends to the more recent and widespread requirement for the sterilization of transgender people as a condition for their obtainment of legal gender recognition. Quietly and devastatingly, the etchings insinuate the ways in which the body’s agency and autonomy are officially appropriated and controlled.

The primacy of text carries over into the fourth room, but here it levitates—a product of light, gravity, and grace. The artist’s holographic imagepoem is equal parts lyrical, sculptural, and filmic. In its spectral presence, the work flirts with a long film tradition: it has the material, flickering quality of early cinema or Structuralist films of the 1960s and ‘70s or even of magic lanterns and optical illusions, while being a decidedly con- temporary phantasmagoria. The blades of the holographic fans propel, Staff would tell you, an interrogation of what it is to be living, sensing, delirious, ecstatic, and suffering—in a world on fire. The poem ends with the repeated, halting assertion: “I AM ALIVE” / “YOU ARE DEAD.” Yet the speaker of the statements remains ambiguous: is it the artist addressing themself, the artist addressing the viewer, or the machine addressing the human?

Central to the exhibition’s final installation is Staff’s new film, La Nuit Américaine. Its title refers to the French term for the analog film technique of shooting by day, with a complex set of lenses and filters, to simulate a deep black-blue night. Though used frequently in early Hollywood films, the deception was often compromised, giving away the trick—the sun creeping into the frame, a reflection that wouldn’t occur in the moon’s soft light. Staff uses the technique, but does nothing to hide that it was filmed during the daytime: people play golf, birds sing, shoppers consume, and families gather under sun umbrellas at the beach. The film’s bald duplicity combines with its sense of increasing anxiousness. It seems to ask: What would happen if we lived in an eternal twilight, if time stuttered, and day be- came indistinguishable from night? Trash and nature, animals and humans fill the screen as if assemblies of the living and undead evoked in the previous rooms have come to congregate there. Without words or narration, the film’s juddering soundtrack of ambient noise, laugh- ter, violas, and cellos, at times rendered syn- thetic and strange, accompany a quickening of image rhythm and cuts wherein the quotidian slides into horror or discomfort. As the film flits from darkness and emptiness to density and abstraction, it ends in a crescendo irradi- ating the entire room with an image of glaring sunlight and strobing, syncopated flashes. This ominous societal portrait ends in what the artist hopes will be a kind of ecstatic release. In Ekstase.

It was the Austrian poet and author Ingeborg Bachmann who once wrote: “I am writing with my burnt hand about the nature of fire.” Staff, too, has taken this task to heart. The fires that Staff encounters are the red-hot embers of social and structural violence and ecological disasters that have become our new normal. Staff’s hand may be burnt as they write, film, and build worlds through their art, and yet, unrelentingly, their exhibition invites visitors to step closer to the fire: it burns images on the retina much like those that result from star- ing too long at the blazing ball of fire and gas that is the sun—gorgeous, but it hurts.