Wong Ping

Golden Shower

18 Jan - 05 May 2019

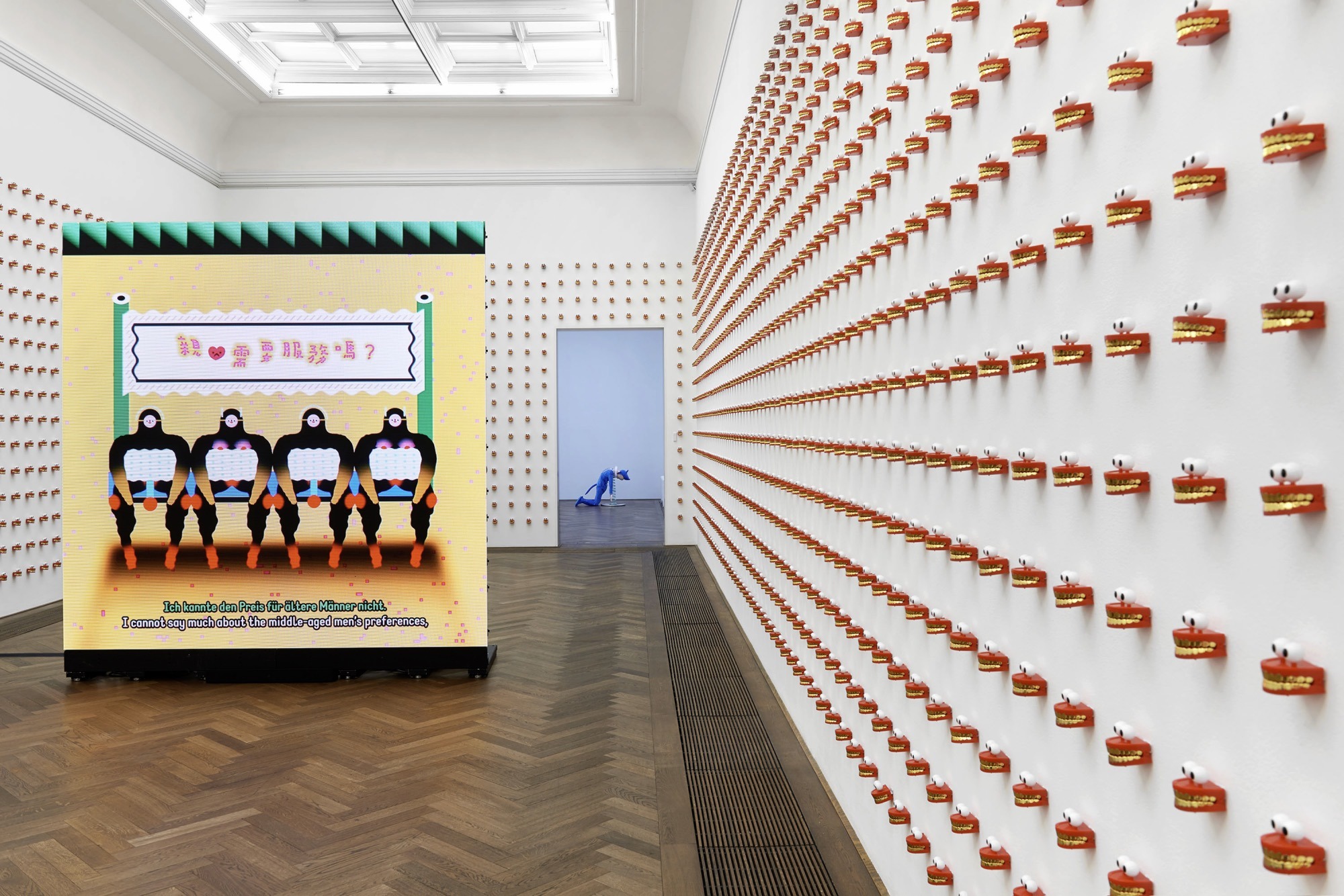

Wong Ping, installation view, Golden Shower, Kunsthalle Basel, 2019. Photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel. Courtesy of the artist and Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong / Shanghai

Wong Ping, installation view, Golden Shower, view on HD film, Dear, can I give you a hand?, 2018, Kunsthalle Basel, 2019. Photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel. Courtesy of the artist, Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong / Shanghai, and Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Courtesy of the artist and Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong / Shanghai

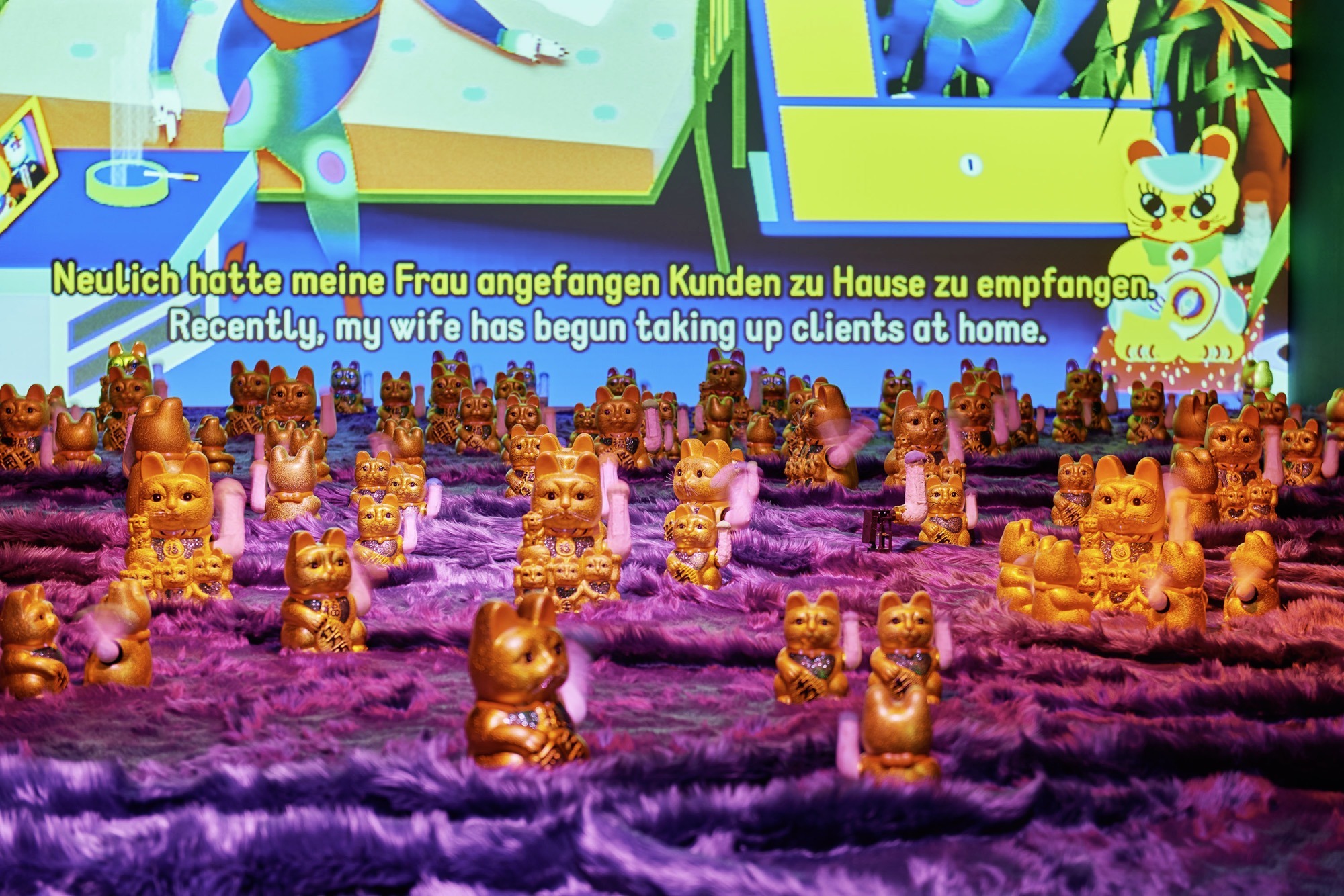

Wong Ping, installation view, Golden Shower, view on, The Ha Ha Ha Online Cemetery Limited, 2019, Kunsthalle Basel, 2019. Photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel. Courtesy of the artist and Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong / Shanghai

Wong Ping, installation view, Golden Shower, Kunsthalle Basel, 2019. Photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel. Courtesy of the artist and Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong / Shanghai

Wong Ping, installation view, Golden Shower, Kunsthalle Basel, 2019. Photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel. Courtesy of the artist and Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong / Shanghai

Wong Ping, installation view, Golden Shower, Kunsthalle Basel, 2019. Photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel. Courtesy of the artist and Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong / Shanghai

Wong Ping, installation view, Golden Shower, view (f.l.t.r.) on, Bestiality rider R, Bestiality rider A, Bestiality rider T, Kunsthalle Basel, 2019. Photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel. Courtesy of the artist and Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong / Shanghai

Wong Ping, installation view, Golden Shower, view on, Bestiality rider A, 2019, Kunsthalle Basel, 2019. Photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel. Courtesy of the artist and Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong / Shanghai

Wong Ping, installation view, Golden Shower, Kunsthalle Basel, 2019. Photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel. Courtesy of the artist and Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong / Shanghai

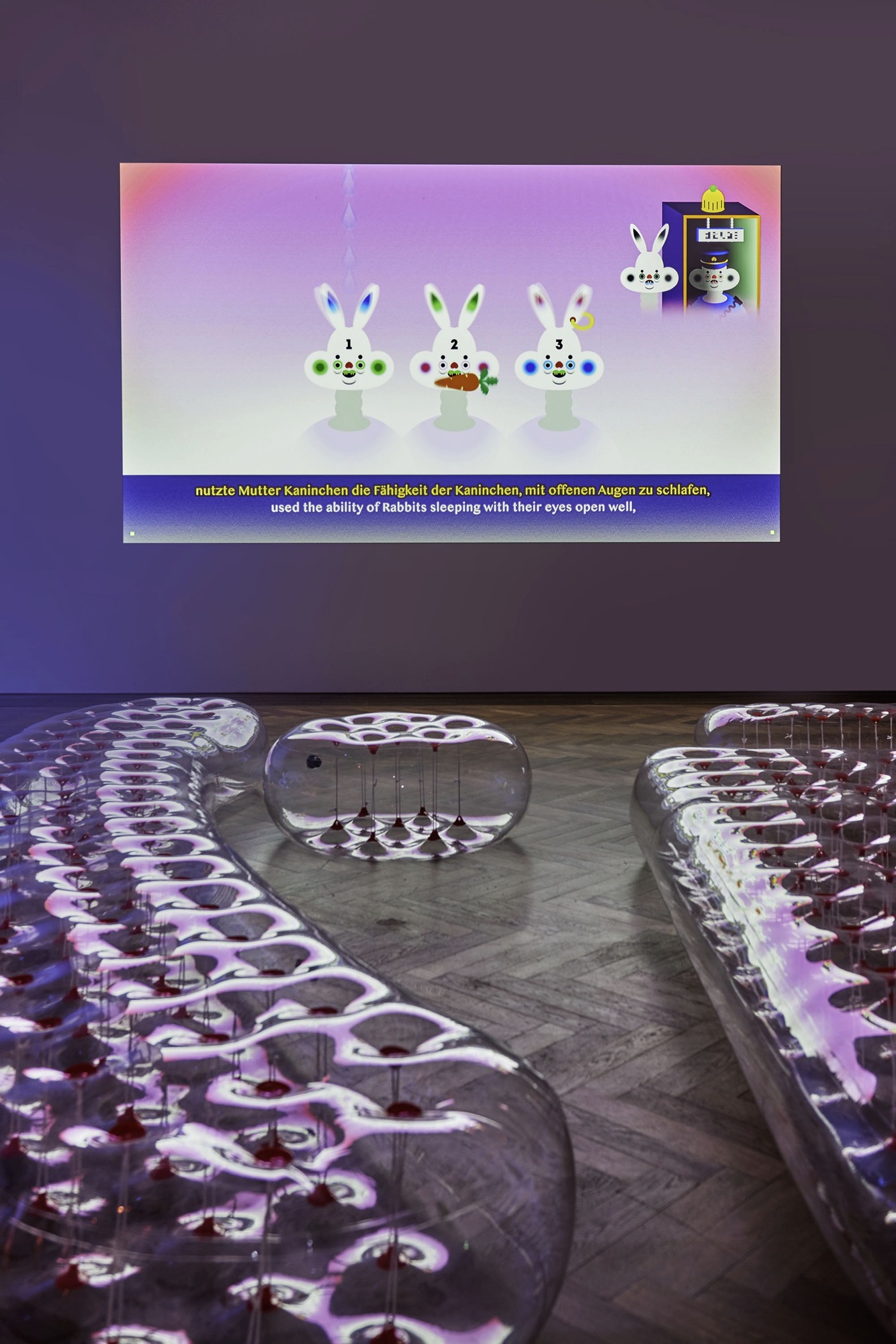

Wong Ping, installation view, Golden Shower, view on HD film, Wong Ping’s Fables 2, 2019, Kunsthalle Basel, 2019. Photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel. Courtesy of the artist and Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong / Shanghai

WONG PING

Golden Shower

18 January – 5 May 2019

The world we live in is twisted. Sexist, ageist, consumerist, post-factual, warmongering, it is all of these things and more. Against this backdrop, we regularly and voyeuristically survey others while we let them watch us via Facebook. We Instagram. We Tinder. We Google. We reveal where we are at any moment, what weʼve eaten, what books we are reading, designating preferences with a thumbs up, with a heart, by swiping right. We scroll and consume ceaseless streams of images and information.

Enter Wong Ping. The Hong Kong native came of age at the dawn of the internet. He didnʼt train as an artist, but studied design. He wrote for years, and then began drawing his stories as animations late at night after his day job at a local television studio. There he worked in postproduction, editing recorded images for broadcast—digitally removing, for example, the safety cables on a falling stunt actor in a crime drama, or replacing the exposed breasts of a show’s female lead with those of a body double. It was a crash course in the media, in digital technology—and in hypocrisy.

The artist points out that what he makes “isn’t very proper animation, as you can see. It’s very simple stuff.” Despite signing his productions “Wong Ping Animation Lab” (to come across as more professional, he says), he executes nearly every aspect himself, from his home. He writes the scripts, draws the animations on his computer, creates the music, and often also narrates the voice-overs in his own deadpan Cantonese. After producing a few animations for a friend’s band and putting them online, interest in his work surged, encouraging him to create and upload more videos, leading to a Hong Kong institutional commission and, soon enough, commercial gallery representation.

What Wong Ping sees as the “simplicity” of his videos—for instance the candy-colored, pixelated approximations of bodies, recalling digitized Legos or 1980s computer games—is what lends them their particularity and appeal. They are both charmingly childlike and graphically explicit, their cartoon forms speak- ing to our contemporary condition with its many pathologies and discontents. Powerless- ness, alienation, exploitation, and misogyny all make an appearance. These are tragic, pathetic, darkly humorous portraits of our time.

Critic Stephanie Bailey rightly said of Wong Ping’s work that it aims to make “individual desires, experiences, and thoughts public... as part of a perversely relatable collective sub- conscious.” Indeed, so much of what the artist writes and then animates is informed by the scenes he witnesses around him, articles he reads, stories he overhears. Yet his approach to portraying the state of the world is not literal; otherwise, he notes, “You might as well just watch the news.”

For instance, the popular “slow food” and “slow living” trends incited one of Wong Ping’s earliest artworks, Slow Sex (2013), an ani- mated lesson on the dangers of rushing copulation. A random thought sparked by a common Cantonese expression informed Doggy Love (2015), in which a teenage boy first mocks, and then falls for, a girl who has breasts on her back. An article about police exploitation of prostitutes inspired Jungle of Desire (2015), in which an impotent male antihero—an animator, as it happens—allows his sexually frustrated wife to prostitute herself while he watches from the closet, becoming obsessed with a corrupt cop who affords his wife “the perfect orgasm.” The creepy, patriarchal lyrics of a 1980s children’s song partly inspired Who’s the Daddy (2017), which centers on a bodybuilding atheist who unpacks his relationship to power by recounting childhood memories of being ordered to “passionately kiss his father,” and his submission to a Christian woman staunchly opposed to premarital sex, but with a predilection for fisting and decidedly bizarre ideas about atonement. Observing an elderly man in his neighborhood mournfully trashing a bag full of VHS porn tapes led to Dear, can I give you a hand? (2018). The aged, toothless protagonist in the animation grapples with the death of his wife, the technological obsolescence of his video collection, desire for his daughter-in-law, and alienation in the digital age. Timid these stories are not.

In his latest videos, Wong Ping turns to the likes of the Grimm Brothers and Aesop’s fables for inspiration: “I want to write a kind of Wong Ping’s Fables for the Modern Age.” These morality tales for children, populated by animal characters, explore everything from the self-loathing generated by impossible beauty standards to the perils of self-righteousness. The artist’s latest fable, the second in what he hopes will be an ongoing series, was com- missioned for this exhibition, his first major institutional solo show, and premieres at Kunsthalle Basel.

Here, the non-chronological survey of new and recent videos is presented in specially conceived environments that lend dimensionality to the animations’ characters and themes. Opening the exhibition, Dear, can I give you a hand? screens on LED panels positioned to form a radiant monolith. It is surrounded by The Ha Ha Ha Online Cemetery Limited (2019), thousands of golden-toothed plastic wind-up toys—an excessive multiplication of the protagonist’s late wife’s prized gold dentures. The second room features Bestiality rider R, Bestiality rider A, and Bestiality rider T (all 2019), three child-size male mannequins dressed in colorful rat costumes mounted on springs so as to resemble freaky children’s playground toys. Just as life’s trials become fodder for the artist’s videos, real-life events inspired this installation: Wong Ping’s home was invaded by a rat while he prepared for this show. Costumed and domesticated, the rats in this strange installation sublimate the artist’s terror and annoyance at the intrusive rodent.

In the room that follows, in which he presents Jungle of Desire, Wong Ping covers the floor with fuzzy purple carpet and a hundred or so Chinese “lucky cats,” their ever-moving paws sculpted into penises with multicolored heads. For the fourth room, which presents Slow Sex, Doggy Love, and Who’s the Daddy, a trio of films in which the assorted penises of the videos’ respective protagonists play a starring role, the artist conceived BONER (2019), a shiny, giant phallus with an illuminated rotating heart at its tip and a column with three jutting video screens. The final room, featuring the videos Wong Ping’s Fables 1 (2018) and Wong Ping’s Fables 2 (2019), is furnished with transparent inflatable seating that forms the artist’s surname in Chinese characters. The space is overseen by the giant inflatable Rabbit 3 in 1 (2019), a character from his latest fable.

Articles about Wong Ping often mention the depravity of his themes. The artist maintains, however, that in the internet era, little remains that could still be considered taboo. Plus, he notes, while sex may be the “language” he uses, “it’s not the message of the work.” Arguably his underlying themes are not sex, or even perversion, but rather a quest for belonging in today’s world: How do we find acceptance and love with others and in ourselves? How do we negotiate loneliness and the isolation of urban life? How do we care for one another? And what beyond these truly existential questions could be more urgent and relevant today?

Ask him to describe his work, and Wong Ping will point you to his favorite song by The Velvet Underground. Its first lines, “I’ll be your mirror / reflect what you are, in case you don’t know,” provide a telling clue to his animations and installations, which are an attempt to respond to our moment, using its own (digital) tools. The artist unravels some of the starkest realities of our own dark age with a touch as biting as it is compassionate and humorous. And if you think Wong Ping’s films are twisted, they are—because the world is, too.

Wong Ping was born 1984 in Hong Kong, CN-HK; he lives and works in Hong Kong.

Golden Shower

18 January – 5 May 2019

The world we live in is twisted. Sexist, ageist, consumerist, post-factual, warmongering, it is all of these things and more. Against this backdrop, we regularly and voyeuristically survey others while we let them watch us via Facebook. We Instagram. We Tinder. We Google. We reveal where we are at any moment, what weʼve eaten, what books we are reading, designating preferences with a thumbs up, with a heart, by swiping right. We scroll and consume ceaseless streams of images and information.

Enter Wong Ping. The Hong Kong native came of age at the dawn of the internet. He didnʼt train as an artist, but studied design. He wrote for years, and then began drawing his stories as animations late at night after his day job at a local television studio. There he worked in postproduction, editing recorded images for broadcast—digitally removing, for example, the safety cables on a falling stunt actor in a crime drama, or replacing the exposed breasts of a show’s female lead with those of a body double. It was a crash course in the media, in digital technology—and in hypocrisy.

The artist points out that what he makes “isn’t very proper animation, as you can see. It’s very simple stuff.” Despite signing his productions “Wong Ping Animation Lab” (to come across as more professional, he says), he executes nearly every aspect himself, from his home. He writes the scripts, draws the animations on his computer, creates the music, and often also narrates the voice-overs in his own deadpan Cantonese. After producing a few animations for a friend’s band and putting them online, interest in his work surged, encouraging him to create and upload more videos, leading to a Hong Kong institutional commission and, soon enough, commercial gallery representation.

What Wong Ping sees as the “simplicity” of his videos—for instance the candy-colored, pixelated approximations of bodies, recalling digitized Legos or 1980s computer games—is what lends them their particularity and appeal. They are both charmingly childlike and graphically explicit, their cartoon forms speak- ing to our contemporary condition with its many pathologies and discontents. Powerless- ness, alienation, exploitation, and misogyny all make an appearance. These are tragic, pathetic, darkly humorous portraits of our time.

Critic Stephanie Bailey rightly said of Wong Ping’s work that it aims to make “individual desires, experiences, and thoughts public... as part of a perversely relatable collective sub- conscious.” Indeed, so much of what the artist writes and then animates is informed by the scenes he witnesses around him, articles he reads, stories he overhears. Yet his approach to portraying the state of the world is not literal; otherwise, he notes, “You might as well just watch the news.”

For instance, the popular “slow food” and “slow living” trends incited one of Wong Ping’s earliest artworks, Slow Sex (2013), an ani- mated lesson on the dangers of rushing copulation. A random thought sparked by a common Cantonese expression informed Doggy Love (2015), in which a teenage boy first mocks, and then falls for, a girl who has breasts on her back. An article about police exploitation of prostitutes inspired Jungle of Desire (2015), in which an impotent male antihero—an animator, as it happens—allows his sexually frustrated wife to prostitute herself while he watches from the closet, becoming obsessed with a corrupt cop who affords his wife “the perfect orgasm.” The creepy, patriarchal lyrics of a 1980s children’s song partly inspired Who’s the Daddy (2017), which centers on a bodybuilding atheist who unpacks his relationship to power by recounting childhood memories of being ordered to “passionately kiss his father,” and his submission to a Christian woman staunchly opposed to premarital sex, but with a predilection for fisting and decidedly bizarre ideas about atonement. Observing an elderly man in his neighborhood mournfully trashing a bag full of VHS porn tapes led to Dear, can I give you a hand? (2018). The aged, toothless protagonist in the animation grapples with the death of his wife, the technological obsolescence of his video collection, desire for his daughter-in-law, and alienation in the digital age. Timid these stories are not.

In his latest videos, Wong Ping turns to the likes of the Grimm Brothers and Aesop’s fables for inspiration: “I want to write a kind of Wong Ping’s Fables for the Modern Age.” These morality tales for children, populated by animal characters, explore everything from the self-loathing generated by impossible beauty standards to the perils of self-righteousness. The artist’s latest fable, the second in what he hopes will be an ongoing series, was com- missioned for this exhibition, his first major institutional solo show, and premieres at Kunsthalle Basel.

Here, the non-chronological survey of new and recent videos is presented in specially conceived environments that lend dimensionality to the animations’ characters and themes. Opening the exhibition, Dear, can I give you a hand? screens on LED panels positioned to form a radiant monolith. It is surrounded by The Ha Ha Ha Online Cemetery Limited (2019), thousands of golden-toothed plastic wind-up toys—an excessive multiplication of the protagonist’s late wife’s prized gold dentures. The second room features Bestiality rider R, Bestiality rider A, and Bestiality rider T (all 2019), three child-size male mannequins dressed in colorful rat costumes mounted on springs so as to resemble freaky children’s playground toys. Just as life’s trials become fodder for the artist’s videos, real-life events inspired this installation: Wong Ping’s home was invaded by a rat while he prepared for this show. Costumed and domesticated, the rats in this strange installation sublimate the artist’s terror and annoyance at the intrusive rodent.

In the room that follows, in which he presents Jungle of Desire, Wong Ping covers the floor with fuzzy purple carpet and a hundred or so Chinese “lucky cats,” their ever-moving paws sculpted into penises with multicolored heads. For the fourth room, which presents Slow Sex, Doggy Love, and Who’s the Daddy, a trio of films in which the assorted penises of the videos’ respective protagonists play a starring role, the artist conceived BONER (2019), a shiny, giant phallus with an illuminated rotating heart at its tip and a column with three jutting video screens. The final room, featuring the videos Wong Ping’s Fables 1 (2018) and Wong Ping’s Fables 2 (2019), is furnished with transparent inflatable seating that forms the artist’s surname in Chinese characters. The space is overseen by the giant inflatable Rabbit 3 in 1 (2019), a character from his latest fable.

Articles about Wong Ping often mention the depravity of his themes. The artist maintains, however, that in the internet era, little remains that could still be considered taboo. Plus, he notes, while sex may be the “language” he uses, “it’s not the message of the work.” Arguably his underlying themes are not sex, or even perversion, but rather a quest for belonging in today’s world: How do we find acceptance and love with others and in ourselves? How do we negotiate loneliness and the isolation of urban life? How do we care for one another? And what beyond these truly existential questions could be more urgent and relevant today?

Ask him to describe his work, and Wong Ping will point you to his favorite song by The Velvet Underground. Its first lines, “I’ll be your mirror / reflect what you are, in case you don’t know,” provide a telling clue to his animations and installations, which are an attempt to respond to our moment, using its own (digital) tools. The artist unravels some of the starkest realities of our own dark age with a touch as biting as it is compassionate and humorous. And if you think Wong Ping’s films are twisted, they are—because the world is, too.

Wong Ping was born 1984 in Hong Kong, CN-HK; he lives and works in Hong Kong.