Pamela Rosenkranz

House of Meme

17 Apr - 04 Jul 2021

Pamela Rosenkranz

House of Meme

Front, Kunsthaus Bregenz, 2021

Photo: Markus Tretter

Courtesy of the artist

© Pamela Rosenkranz, Kunsthaus Bregenz

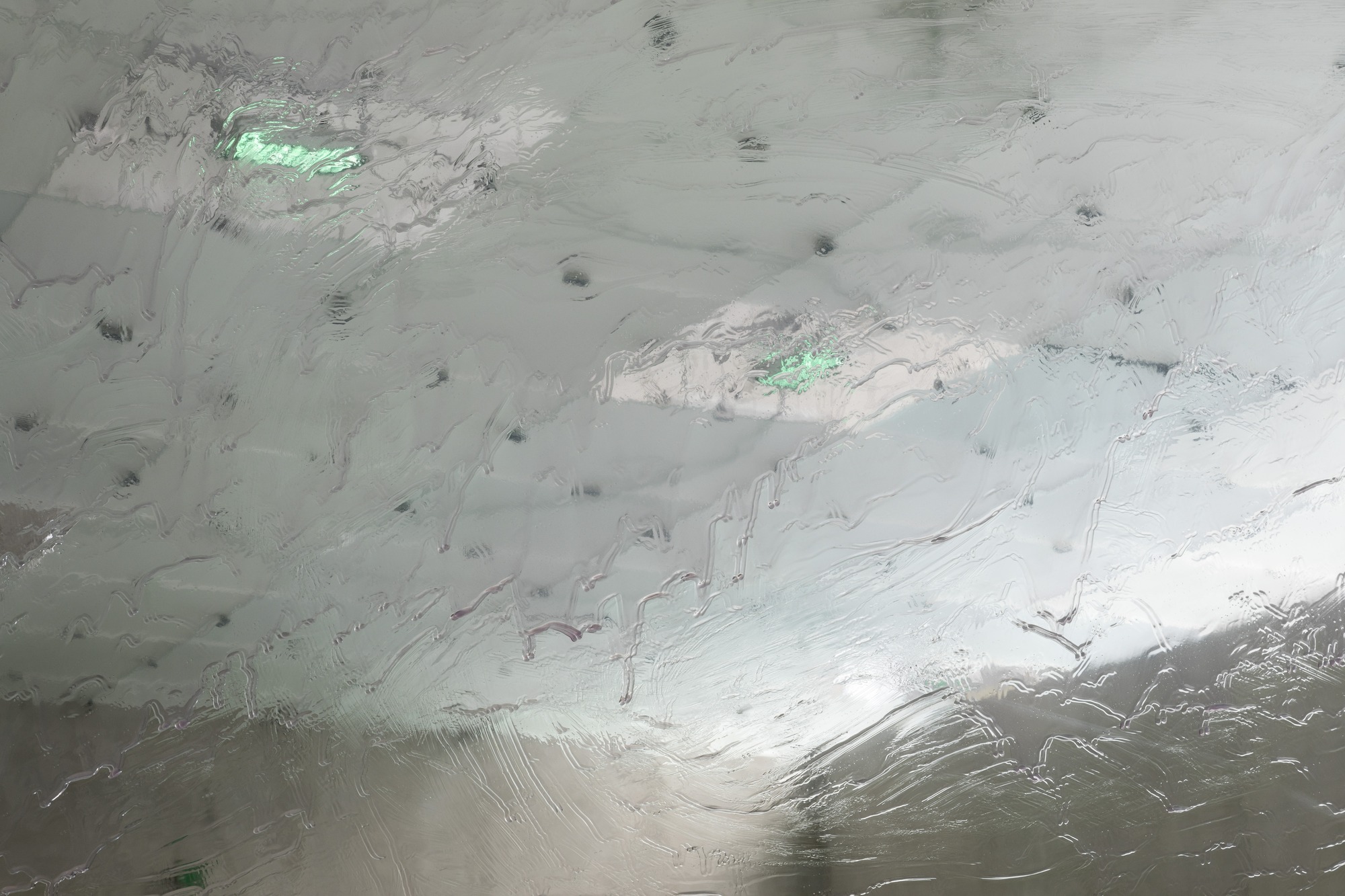

House of Meme

Front, Kunsthaus Bregenz, 2021

Photo: Markus Tretter

Courtesy of the artist

© Pamela Rosenkranz, Kunsthaus Bregenz

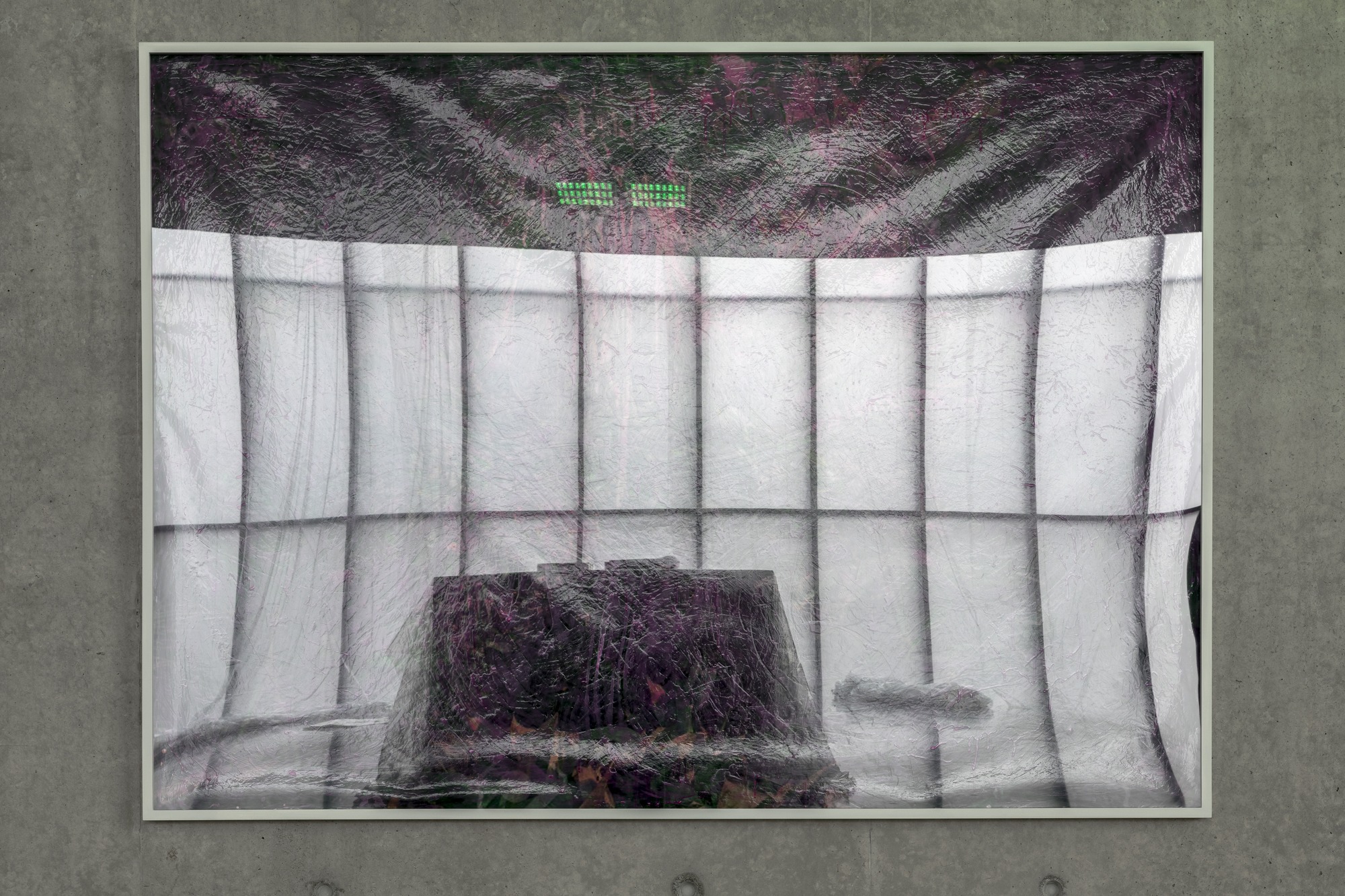

Pamela Rosenkranz

House of Meme

Installation view ground floor, Kunsthaus Bregenz, 2021

Photo: Markus Tretter

Courtesy of the artist

© Pamela Rosenkranz, Kunsthaus Bregenz

House of Meme

Installation view ground floor, Kunsthaus Bregenz, 2021

Photo: Markus Tretter

Courtesy of the artist

© Pamela Rosenkranz, Kunsthaus Bregenz

Pamela Rosenkranz

House of Meme

Installation view ground floor, Kunsthaus Bregenz, 2021

Photo: Markus Tretter

Courtesy of the artist

© Pamela Rosenkranz, Kunsthaus Bregenz

House of Meme

Installation view ground floor, Kunsthaus Bregenz, 2021

Photo: Markus Tretter

Courtesy of the artist

© Pamela Rosenkranz, Kunsthaus Bregenz

Pamela Rosenkranz

House of Meme

Installation view ground floor, Kunsthaus Bregenz, 2021

Photo: Markus Tretter

Courtesy of the artist

© Pamela Rosenkranz, Kunsthaus Bregenz

House of Meme

Installation view ground floor, Kunsthaus Bregenz, 2021

Photo: Markus Tretter

Courtesy of the artist

© Pamela Rosenkranz, Kunsthaus Bregenz

Pamela Rosenkranz

House of Meme

Installation view ground floor, Kunsthaus Bregenz, 2021

Photo: Markus Tretter

Courtesy of the artist

© Pamela Rosenkranz, Kunsthaus Bregenz

House of Meme

Installation view ground floor, Kunsthaus Bregenz, 2021

Photo: Markus Tretter

Courtesy of the artist

© Pamela Rosenkranz, Kunsthaus Bregenz

Pamela Rosenkranz

House of Meme

Installation view ground floor, Kunsthaus Bregenz, 2021

Photo: Markus Tretter

Courtesy of the artist

© Pamela Rosenkranz, Kunsthaus Bregenz

House of Meme

Installation view ground floor, Kunsthaus Bregenz, 2021

Photo: Markus Tretter

Courtesy of the artist

© Pamela Rosenkranz, Kunsthaus Bregenz

Pamela Rosenkranz

House of Meme

Installation view first floor, Kunsthaus Bregenz, 2021

Photo: Markus Tretter

Courtesy of the artist

© Pamela Rosenkranz, Kunsthaus Bregenz

House of Meme

Installation view first floor, Kunsthaus Bregenz, 2021

Photo: Markus Tretter

Courtesy of the artist

© Pamela Rosenkranz, Kunsthaus Bregenz

Pamela Rosenkranz

House of Meme

Installation view second floor, Kunsthaus Bregenz, 2021

Photo: Markus Tretter

Courtesy of the artist

© Pamela Rosenkranz, Kunsthaus Bregenz

House of Meme

Installation view second floor, Kunsthaus Bregenz, 2021

Photo: Markus Tretter

Courtesy of the artist

© Pamela Rosenkranz, Kunsthaus Bregenz

Pamela Rosenkranz

House of Meme

Installation view third floor, Kunsthaus Bregenz, 2021

Photo: Markus Tretter

Courtesy of the artist

© Pamela Rosenkranz, Kunsthaus Bregenz

House of Meme

Installation view third floor, Kunsthaus Bregenz, 2021

Photo: Markus Tretter

Courtesy of the artist

© Pamela Rosenkranz, Kunsthaus Bregenz

Pamela Rosenkranz

House of Meme

Installation view third floor, Kunsthaus Bregenz, 2021

Photo: Markus Tretter

Courtesy of the artist

© Pamela Rosenkranz, Kunsthaus Bregenz

House of Meme

Installation view third floor, Kunsthaus Bregenz, 2021

Photo: Markus Tretter

Courtesy of the artist

© Pamela Rosenkranz, Kunsthaus Bregenz

“Particles of the Internet, shimmering script, intangible. Old knowledge rolls off, and yet it carries the mythology of entire cultures and generates deeply rooted reflexes.”

Pamela Rosenkranz

How permeable are we, how absorbent? Pamela Rosenkranz perceives people as membranes. She favors trenchant means for her exhibitions. In the one at Kunsthaus Bregenz she is replying to the building’s architecture. While Peter Zumthor searches for phenomenological effects: light, sound, coolness, sensitivity, and the general disposition of individuals all playing a significant role, Pamela Rosenkranz questions the certainties of authentic experience. There is no such thing as pure experience or an immunity to invisible existences, which is something that has become abundantly clear during the pandemic. The human condition is modeled both osmotically and artificially.

Light sources hang in the spaces like Gothic windows. Their outward facing surfaces display fields of intense blue. They do not constitute images in any ordinary sense, but are rather glass windows emanating a saturated, intense blue light, accumulating like sediment within spaces of glass and concrete. Screens shimmer, providing depth, blue being the color of contemplation, associated with coolness, limitlessness, and desire. In many religions blue is also a symbol of ascension and salvation. But colors are also events in terms of physics. They possess measurable wavelengths associated with the development of the sense of sight that took place underwater during prehistoric times. Rosenkranz employs aesthetics as a fundamental means of research into the sensory, placing it closer to the experiments of the late-Impressionists than Yves Klein, who produced monochrome blue paintings, consequently “reifying” (Rosenkranz) the hue by patenting it.

What are color and light? How do smells occur and how do the receptors sensitive to them behave? How are sound and vibration registered? And isn’t a building, similarly to a living being, also able to collect and preserve such experiences as fluctuations in temperature, degrees of humidity, and tremors? Acoustic vibrations may be evanescent, but do not disappear. The same applies to neurological intrusions and biochemical substances that remain nondegradable. Humans are no longer sovereign subjects, but synthetic ones.

Rosenkranz suggests such a mingling of synthetic and natural substances in arcane mise-en-scènes. Plastic sheeting shimmers, sound waves vibrate, humidity swirls, and an archaic smell that is artificially created pervades the spaces. Everything flows; this ancient philosophical observation is now gaining new relevance through the emergence of the artificial.

The upper floor is home to a snake. It is a computer controlled machine that reacts to electromagnetic radiation, sidewinding, raising its head and observing its surroundings, or biding its time motionlessly on the floor. Reflective scales conceal its network of sensors and semiconductors, while the inaudible sound of electronic noise recharges it. In terms of art history, the “snakebot” may be located within the tradition of kinetic sculpture, but is nevertheless based primarily upon scientific attempts to replace not only living beings with robots but also the organic with algorithms. Although its appearance could be perceived as artificial and unnatural, the robotic serpent still provokes feelings from the depths of our evolutionary past. Our eyes specialize in detecting the patterns of both a snake’s scales and its movements. Human eyesight has apparently improved significantly during evolution. What do we see when encountering a robot snake? Danger, beauty, or algorithms?

The exhibition dissolves any separation between the natural and artificial. It becomes an animated “habitat” for a robotic creature that is controlled by our devices and which connects everything. Its perceptions reverberate throughout the entire building. Signals from our cell phones are already being fed into it even as we first encounter it. The movements of the snake in relation to our bodies, the contemplation of art, or what is being represented as a deeply archaic need in humans, but which also apprehends us physically, permeates the exhibition. The building becomes an organism of expanded biological interactivity.

Biography

Pamela Rosenkranz

Pamela Rosenkranz (*1979 in Uri, Switzerland) lives and works in Zurich and Zug. In 2004 she graduated with a Master of Fine Arts from Bern University of the Arts; she also studied comparative literature at the University of Zurich. She was already receiving a great deal of international attention while still a student.

Her most recent exhibitions include: Alien Culture, GAMeC Bergamo (2017), IF THE SNAKE, Okayama Art Summit, Okayama (2019), Là où les eaux se mêlent, 15th Biennale de Lyon (2019), Leaving the Echo Chamber, Sharjah Biennial 14 (2019), and Slight Agitation 2/4: Pamela Rosenkranz at Fondazione Prada, Milan (2017).

In 2015 Rosenkranz represented Switzerland at the Venice Biennale.

KUB Billboards

Pamela Rosenkranz

House of Meme

17 | 04 — 04 I 07 I 2021

Digital imagery, magical green, and layers of pink radiate from the billboards along Seestraße in Bregenz. Pamela Rosenkranz locates such imagery on the Internet, on the sites of stock photography agencies, enhancing them with a mixture of shimmering materials and pigments in complementary colors. The result is an imagery whose original motif is, to an extent, either emphasized or concealed by the intensity of its colors. The images become exposed in their materiality, employing strategies of both shielding and revealing that not only protect them but also expose them to the elements, becoming part of a biological process that even works of art are subjected to.

The KUB billboards located on Seestraße, the main thoroughfare in Bregenz, are an integral part of Kunsthaus Bregenz’s program, extending each KUB exhibition into public space.

KUB Publication

Pamela Rosenkranz

House of Meme

Pamela Rosenkranz addresses the phenomenon of perception. In her works, in which she uses materials as diverse as light, plastics containing endocrine disruptors, dyes, polymers, and even smells, she explores the interactions between sensory impressions and perception. Neuroscientific findings inform her work, together with art historical references, as well as objects from quotidian culture. Shumon Basar, Thomas D. Trummer, and further authors examine the artist’s distinctive working methods from differing perspectives and expound on the concept of the installations on display at Kunsthaus Bregenz. The publication, which has been conceived as an artist’s book and catalogue, is being developed in close collaboration with Pamela Rosenkranz.

Edited by Thomas D. Trummer, Kunsthaus Bregenz

Essays by Shumon Basar, Thomas D. Trummer, et al.

Graphic design: Teo Schifferli

German / English, approx. 20 x 26 cm, approx. 164 pages

Date of publication: June 2021

Pamela Rosenkranz

How permeable are we, how absorbent? Pamela Rosenkranz perceives people as membranes. She favors trenchant means for her exhibitions. In the one at Kunsthaus Bregenz she is replying to the building’s architecture. While Peter Zumthor searches for phenomenological effects: light, sound, coolness, sensitivity, and the general disposition of individuals all playing a significant role, Pamela Rosenkranz questions the certainties of authentic experience. There is no such thing as pure experience or an immunity to invisible existences, which is something that has become abundantly clear during the pandemic. The human condition is modeled both osmotically and artificially.

Light sources hang in the spaces like Gothic windows. Their outward facing surfaces display fields of intense blue. They do not constitute images in any ordinary sense, but are rather glass windows emanating a saturated, intense blue light, accumulating like sediment within spaces of glass and concrete. Screens shimmer, providing depth, blue being the color of contemplation, associated with coolness, limitlessness, and desire. In many religions blue is also a symbol of ascension and salvation. But colors are also events in terms of physics. They possess measurable wavelengths associated with the development of the sense of sight that took place underwater during prehistoric times. Rosenkranz employs aesthetics as a fundamental means of research into the sensory, placing it closer to the experiments of the late-Impressionists than Yves Klein, who produced monochrome blue paintings, consequently “reifying” (Rosenkranz) the hue by patenting it.

What are color and light? How do smells occur and how do the receptors sensitive to them behave? How are sound and vibration registered? And isn’t a building, similarly to a living being, also able to collect and preserve such experiences as fluctuations in temperature, degrees of humidity, and tremors? Acoustic vibrations may be evanescent, but do not disappear. The same applies to neurological intrusions and biochemical substances that remain nondegradable. Humans are no longer sovereign subjects, but synthetic ones.

Rosenkranz suggests such a mingling of synthetic and natural substances in arcane mise-en-scènes. Plastic sheeting shimmers, sound waves vibrate, humidity swirls, and an archaic smell that is artificially created pervades the spaces. Everything flows; this ancient philosophical observation is now gaining new relevance through the emergence of the artificial.

The upper floor is home to a snake. It is a computer controlled machine that reacts to electromagnetic radiation, sidewinding, raising its head and observing its surroundings, or biding its time motionlessly on the floor. Reflective scales conceal its network of sensors and semiconductors, while the inaudible sound of electronic noise recharges it. In terms of art history, the “snakebot” may be located within the tradition of kinetic sculpture, but is nevertheless based primarily upon scientific attempts to replace not only living beings with robots but also the organic with algorithms. Although its appearance could be perceived as artificial and unnatural, the robotic serpent still provokes feelings from the depths of our evolutionary past. Our eyes specialize in detecting the patterns of both a snake’s scales and its movements. Human eyesight has apparently improved significantly during evolution. What do we see when encountering a robot snake? Danger, beauty, or algorithms?

The exhibition dissolves any separation between the natural and artificial. It becomes an animated “habitat” for a robotic creature that is controlled by our devices and which connects everything. Its perceptions reverberate throughout the entire building. Signals from our cell phones are already being fed into it even as we first encounter it. The movements of the snake in relation to our bodies, the contemplation of art, or what is being represented as a deeply archaic need in humans, but which also apprehends us physically, permeates the exhibition. The building becomes an organism of expanded biological interactivity.

Biography

Pamela Rosenkranz

Pamela Rosenkranz (*1979 in Uri, Switzerland) lives and works in Zurich and Zug. In 2004 she graduated with a Master of Fine Arts from Bern University of the Arts; she also studied comparative literature at the University of Zurich. She was already receiving a great deal of international attention while still a student.

Her most recent exhibitions include: Alien Culture, GAMeC Bergamo (2017), IF THE SNAKE, Okayama Art Summit, Okayama (2019), Là où les eaux se mêlent, 15th Biennale de Lyon (2019), Leaving the Echo Chamber, Sharjah Biennial 14 (2019), and Slight Agitation 2/4: Pamela Rosenkranz at Fondazione Prada, Milan (2017).

In 2015 Rosenkranz represented Switzerland at the Venice Biennale.

KUB Billboards

Pamela Rosenkranz

House of Meme

17 | 04 — 04 I 07 I 2021

Digital imagery, magical green, and layers of pink radiate from the billboards along Seestraße in Bregenz. Pamela Rosenkranz locates such imagery on the Internet, on the sites of stock photography agencies, enhancing them with a mixture of shimmering materials and pigments in complementary colors. The result is an imagery whose original motif is, to an extent, either emphasized or concealed by the intensity of its colors. The images become exposed in their materiality, employing strategies of both shielding and revealing that not only protect them but also expose them to the elements, becoming part of a biological process that even works of art are subjected to.

The KUB billboards located on Seestraße, the main thoroughfare in Bregenz, are an integral part of Kunsthaus Bregenz’s program, extending each KUB exhibition into public space.

KUB Publication

Pamela Rosenkranz

House of Meme

Pamela Rosenkranz addresses the phenomenon of perception. In her works, in which she uses materials as diverse as light, plastics containing endocrine disruptors, dyes, polymers, and even smells, she explores the interactions between sensory impressions and perception. Neuroscientific findings inform her work, together with art historical references, as well as objects from quotidian culture. Shumon Basar, Thomas D. Trummer, and further authors examine the artist’s distinctive working methods from differing perspectives and expound on the concept of the installations on display at Kunsthaus Bregenz. The publication, which has been conceived as an artist’s book and catalogue, is being developed in close collaboration with Pamela Rosenkranz.

Edited by Thomas D. Trummer, Kunsthaus Bregenz

Essays by Shumon Basar, Thomas D. Trummer, et al.

Graphic design: Teo Schifferli

German / English, approx. 20 x 26 cm, approx. 164 pages

Date of publication: June 2021