Charmion von Wiegand

25 Mar - 13 Aug 2023

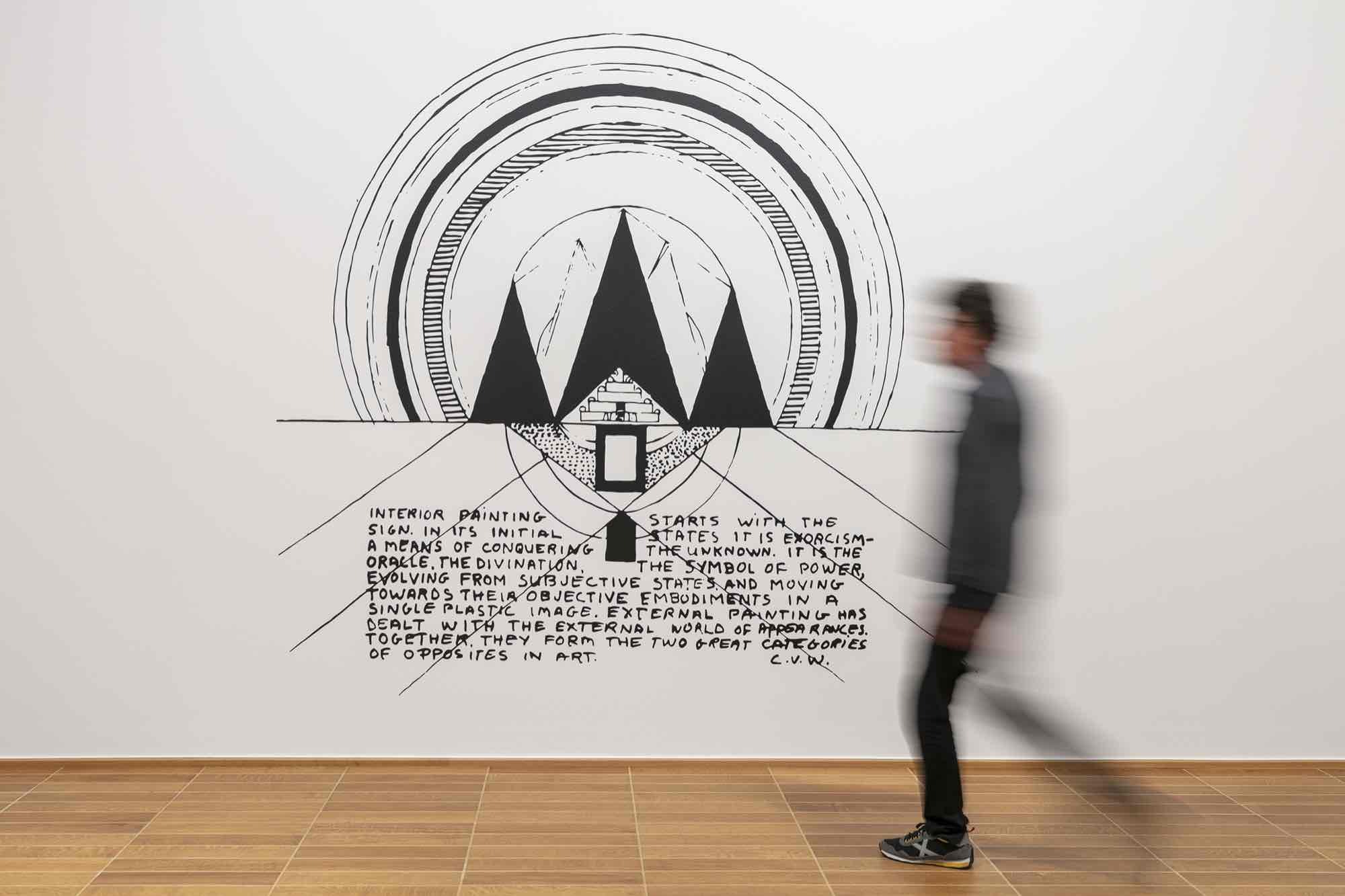

In the spring of 2023, the Kunstmuseum Basel presents a monographic exhibition of the work of the American journalist, art critic, and painter Charmion von Wiegand (1896– 1983). The first retrospective of her oeuvre in almost four decades, it is also her very first institutional exhibition in Europe, tracing her career from her early days as a correspondent in 1930s post-revolutionary Moscow to her late work in painting. With forty-nine paintings and sketches and a wide assortment of documents, the display reconstructs the evolution of a now-forgotten artist who lived transcultural openness and diversity and translated them into visual art.

Charmion von Wiegand won acclaim as an artist in the mid-twentieth century with paintings that fused the conventions of geometric abstraction with the shapes and colors of Far Eastern pictorial symbolism. A native of Chicago, she grew up in Florida, Arizona, San Francisco, and Berlin and arrived in New York in 1915. As an active member of the literary circles of the 1920s, she was intimately familiar with the New York scene. In the 1930s, she reported from Soviet Moscow, making her mark as a critic for various publications. Her breakthrough as an artist came in 1945, when she showed a work in the visionary exhibition The Women at Peggy Guggenheim’s gallery Art of This Century, followed by her first solo exhibition, at a renowned small gallery in New York, in 1947.

The influence of Piet Mondrian

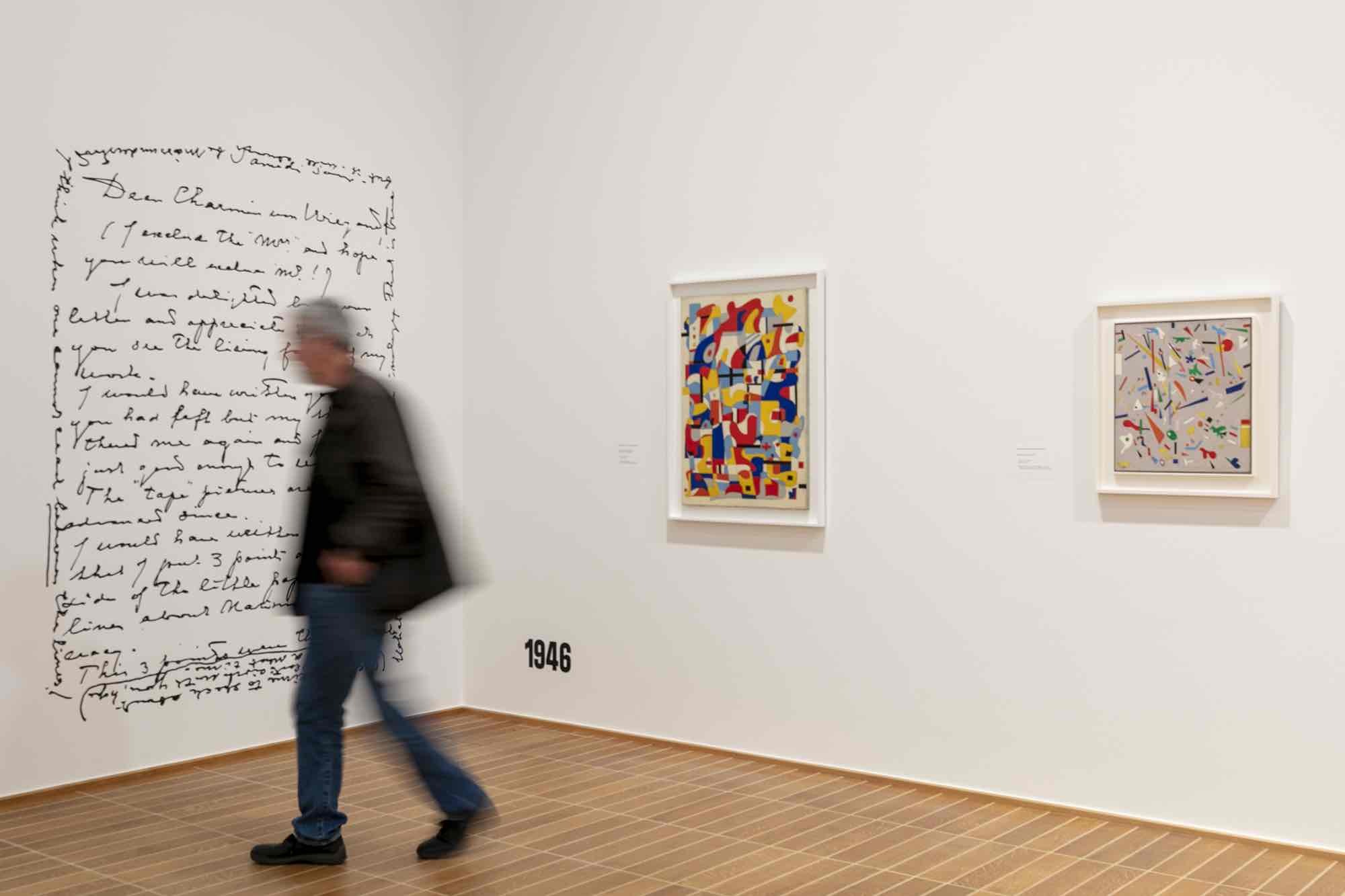

Having reviewed the pamphlet Five on Revolutionary Art, which extolled Piet Mondrian as “truly revolutionary,” von Wiegand got in touch with the artist, who had recently emigrated to the U.S., in 1941. The encounter proved highly consequential for her subsequent pursuits. She not only introduced Mondrian to New York society, wrote about his work, edited his writings, and made sketches showing an early stage of his unfinished painting Victory Boogie-Woogie (1942–44). Her own painterly output, too, was influenced by the Dutch artist. The sustained engagement with Mondrian’s creative approach strengthened von Wiegand’s conviction that geometric abstraction was not bound to remain purely formal, that it was capable of rendering substantive content.

This insight is reflected, for instance, in the “City paintings” she made after Mondrian’s death in 1944. At the time, she was developing her work in an ongoing exchange of ideas with the so-called “Mondrian Circle,” a group of American artists that also included the Swiss émigré painter Fritz Glarner. Other key points of reference of this period included Wassily Kandinsky and Hans Arp. Von Wiegand soon jettisoned the reduction to red, yellow, blue, employing expanded palettes to visualize the inspirations she received from the writings of Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, the founder of Theosophy. She was especially fascinated by Blavatsky’s discussions of Buddhist color codes and the mandala and other geometric shapes.

Spirituality and Buddhism

Beginning in the 1950s, von Wiegand took an interest in the spiritual practice of Tibetan Buddhism. In an extension of her engagement with Theosophy, she deepened her understanding of Tibetan art by studying ethnological literature. She later took a leading role in establishing the Tibet Center in New York. As a practicing Buddhist, she now focused her energies on devising a creative vocabulary that allowed her to use form and color also as media of spiritual expression. As Haema Sivanesan writes in the catalogue accompanying the exhibition, von Wiegand thus developed the visual language for a “modern transcultural Buddhism.”

The exhibition Charmion von Wiegand features forty-nine paintings and works on paper provided by Swiss and international lenders. The great majority of the works come from the artist’s estate, complemented by loans from the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York; the Seattle Art Museum; the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; and other collections.

Curator: Maja Wismer with Martin Brauen

Charmion von Wiegand won acclaim as an artist in the mid-twentieth century with paintings that fused the conventions of geometric abstraction with the shapes and colors of Far Eastern pictorial symbolism. A native of Chicago, she grew up in Florida, Arizona, San Francisco, and Berlin and arrived in New York in 1915. As an active member of the literary circles of the 1920s, she was intimately familiar with the New York scene. In the 1930s, she reported from Soviet Moscow, making her mark as a critic for various publications. Her breakthrough as an artist came in 1945, when she showed a work in the visionary exhibition The Women at Peggy Guggenheim’s gallery Art of This Century, followed by her first solo exhibition, at a renowned small gallery in New York, in 1947.

The influence of Piet Mondrian

Having reviewed the pamphlet Five on Revolutionary Art, which extolled Piet Mondrian as “truly revolutionary,” von Wiegand got in touch with the artist, who had recently emigrated to the U.S., in 1941. The encounter proved highly consequential for her subsequent pursuits. She not only introduced Mondrian to New York society, wrote about his work, edited his writings, and made sketches showing an early stage of his unfinished painting Victory Boogie-Woogie (1942–44). Her own painterly output, too, was influenced by the Dutch artist. The sustained engagement with Mondrian’s creative approach strengthened von Wiegand’s conviction that geometric abstraction was not bound to remain purely formal, that it was capable of rendering substantive content.

This insight is reflected, for instance, in the “City paintings” she made after Mondrian’s death in 1944. At the time, she was developing her work in an ongoing exchange of ideas with the so-called “Mondrian Circle,” a group of American artists that also included the Swiss émigré painter Fritz Glarner. Other key points of reference of this period included Wassily Kandinsky and Hans Arp. Von Wiegand soon jettisoned the reduction to red, yellow, blue, employing expanded palettes to visualize the inspirations she received from the writings of Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, the founder of Theosophy. She was especially fascinated by Blavatsky’s discussions of Buddhist color codes and the mandala and other geometric shapes.

Spirituality and Buddhism

Beginning in the 1950s, von Wiegand took an interest in the spiritual practice of Tibetan Buddhism. In an extension of her engagement with Theosophy, she deepened her understanding of Tibetan art by studying ethnological literature. She later took a leading role in establishing the Tibet Center in New York. As a practicing Buddhist, she now focused her energies on devising a creative vocabulary that allowed her to use form and color also as media of spiritual expression. As Haema Sivanesan writes in the catalogue accompanying the exhibition, von Wiegand thus developed the visual language for a “modern transcultural Buddhism.”

The exhibition Charmion von Wiegand features forty-nine paintings and works on paper provided by Swiss and international lenders. The great majority of the works come from the artist’s estate, complemented by loans from the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York; the Seattle Art Museum; the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; and other collections.

Curator: Maja Wismer with Martin Brauen