Class Relations

Phantoms of Perception

27 Oct 2018 - 27 Jan 2019

PHANTOMS OF PERCEPTION

27 October 2018 - 27 January 2019

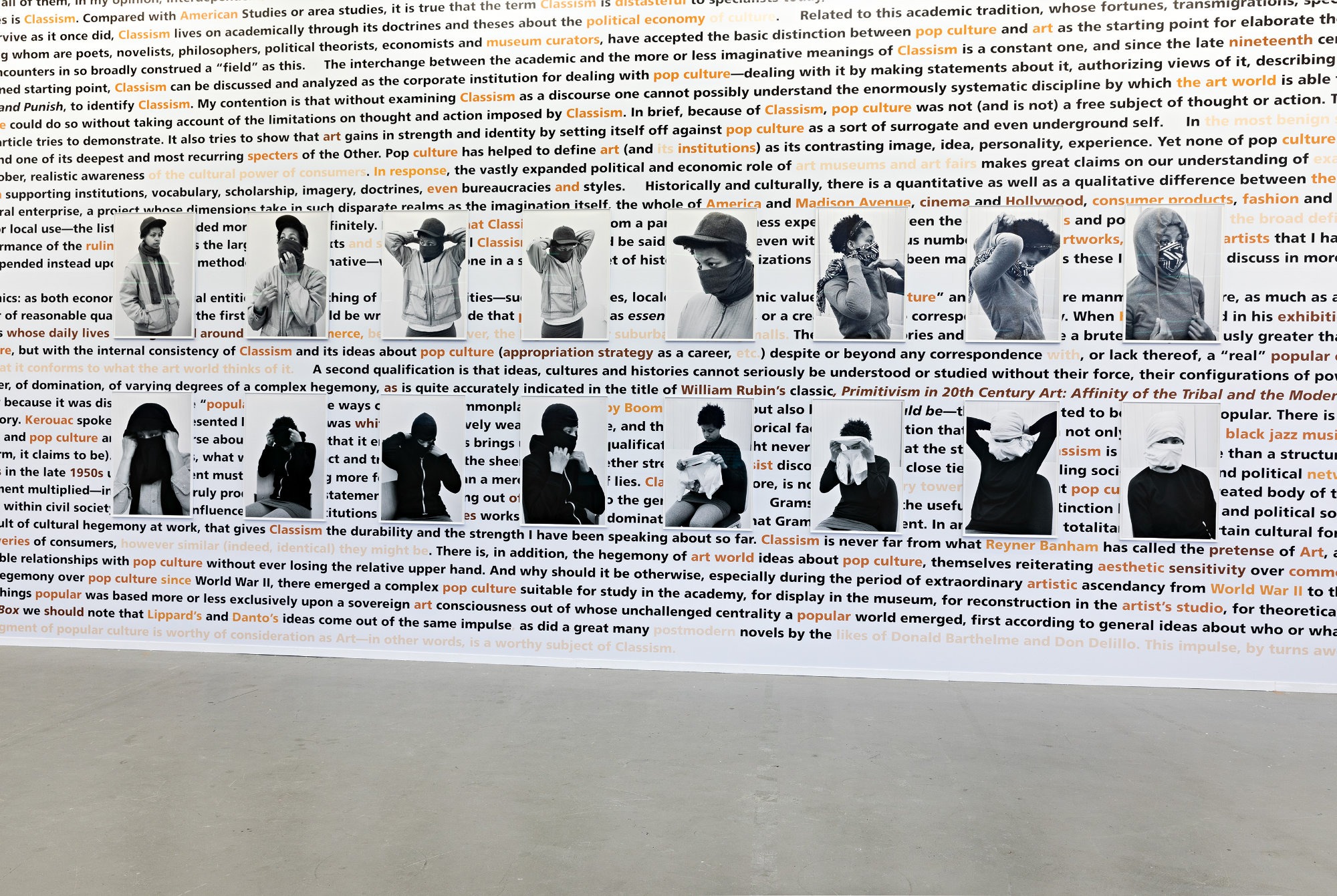

Monica Bonvicini, Sigmar Polke, Tobias Zielony, Neïl Beloufa, Benedikte Bjerre, Jan Peter Hammer, Thomas Hirschhorn, Sven Johne, Los Capinteros, Henrike Naumann, Driss Ouadahi, Joe Scanlan, Andrzej Steinbach, Anna Witt, Ariel Reichman, Katie Holten, Harun Farocki / Antje Ehmann and Jean-Marie Straub / Danièle Huillet

The group exhibition Klassenverhältnisse – Phantoms of Perception deal with narratives of class affiliation, decline and social differences that are constantly present in public perception as rarely articulated phantoms and features artists whose works compel us to rivet on such interrelations that lie outside of our conscious field of vision, although they crucially determine the way we perceive social coexistence.

The starting point of the exhibition Klassenverhältnisse (Class Relations) and at the same time an invitation to rediscover an outstanding cinematic work less well known in Germany is Klassenverhältnisse of the French filmmaker couple Jean-Marie Straub (*1933) and Danièle Huillet (1936-2006) from 1984, a film adaptation of Franz Kafka’s novel fragment The Missing Person, shot in Hamburg. The film tells the story of young Karl Roßmann who searches for but fails to find his place in society. Klassenverhältnisse starts with a much-discussed and seminal image: For minutes on end, the camera shows a static shot of the Störtebeker monument that had been erected two years earlier in what is today HafenCity near his place of execution on the Grasbrook. The naked and chained privateer in front of the huge counting houses commemorates the legendary breach of promise by Hamburg’s mayor It is said that he promised Störtebeker to free all members of the crew he could walk past after being beheaded. Störtebeker made it to the eleventh man, yet the mayor had the entire crew executed. With this first image, Straub/Huillet immediately focus on the fragility of the social order, law, freedom, and hierarchies seemingly cast in bronze for eternity.

The camera in the complexly constructed image spaces of Klassenverhältnisse rarely assumes a position corresponding with the usual viewing habits in cinema. Events are constantly taking place in an expanded space that the viewer perceives but does not see directly. The image of the ghost is central in the discussions on social realities, as Jaques Derrida describes the ghost as the “present without presence”. The art historian and theorist of perception Ernst Gombrich described “phantom percepts” as the circumstance that we never only see what we see, but always anticipate, remember, and think along with the Using “phantom percepts,” artistic works are on view that expand the space of perception and problematize social interrelations, while at the same time employing a technique and a language that engender these interrelations. But Phantoms of Perception refers to more: To how artists take on perspectives that other people usually don’t. Since 1920, film shots from such an angle have been called phantom shots in the USA. Harun Farocki, who played a French immigrant in Class Relations and made a film about the shooting at the same time, used this term in his analyses of today’s technical images.

The exhibition aims to break away from familiar thought structures: Is it possible to work with phantom percepts to redirect the gaze of the viewers to new ways of seeing? Can their interpreting expectations be used to draw attention to another object, to other contexts? Can disturbances be caused that suddenly make phantoms already located in the same space visible?

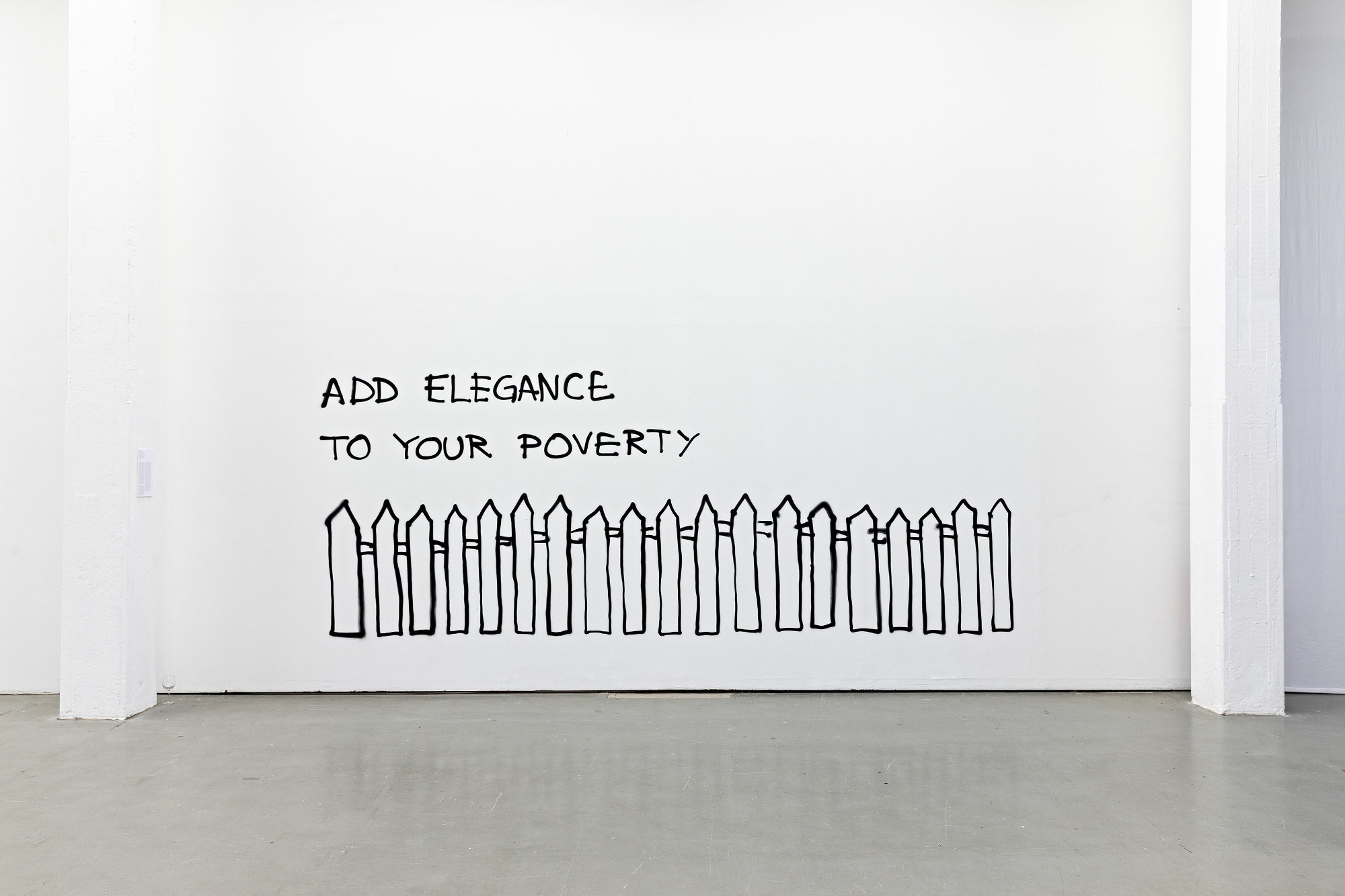

The central questions of the show have to do with the current problems posed by the illusion of a classless society: Class relations exist, but as phantoms, because the concepts that describe them are hardly present anymore in the public discourse, in culture and the media. The exhibition takes a look behind the mechanisms with which artists expand our scope of perception in the inner space of contemporary art, and at the social realities with which they confront us there. It examines the phantoms currently gripping our society in power mechanisms, in the causes of rising rightwing populism, and in the apparently spreading fear of social and economic decline.

Adhering to Erhard’s maxim of “prosperity for all,” millions of Germans had one goal that could actually be achieved: a place in the middle class. It meant more growth and social peace that would benefit all. Against this backdrop, class appears a hopelessly outdated concept, as a relic from the class struggles of the 1970s. Didier Eribon, however, points out that “when one simply eliminates ‘classes’ and class relations from the categories of thought and comprehension, and thus from the political discourse, one by no means avoids that those who are objectively affected by the relations behind these terms feel themselves collectively abandoned.”The book’s success and core argument indicate that there clearly was and still is a void in the public discourse, a lacking awareness of the social realities, especially in (leftist) politics and among the well-educated populations in metropolitan regions.

The exhibition negotiates these themes, which are at the center of the challenges that must be faced for societies to succeed in the 21st century, not as abstract and aloof ones, but with the experiential space of very specific realities of life by setting Karl Roßmann’s universal odyssey in relation to Hamburg.

The exhibition is curated by Bettina Steinbrügge, Benjamin Fellmann and Tobias Peper.