EDGE, ORDER, RUPTURE

04 Apr - 04 May 2013

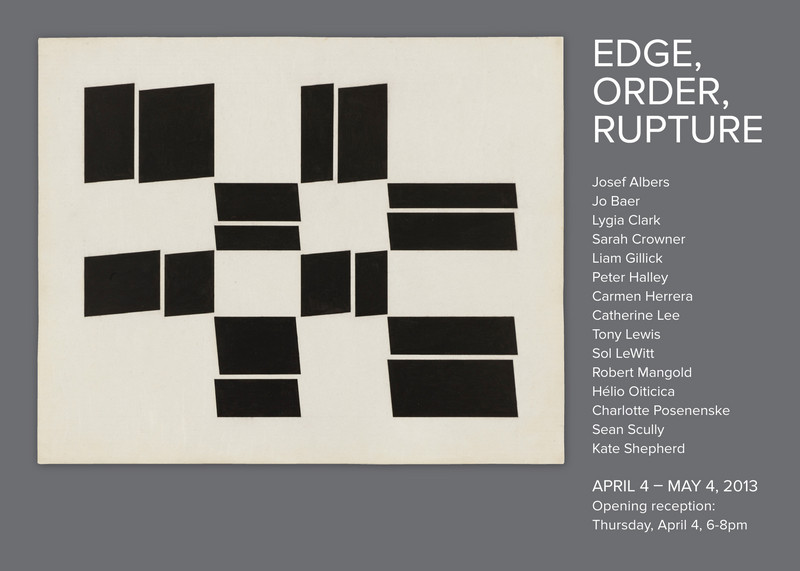

Metaesquema 286, 1958

© Projeto Hélio Oiticica, Rio de Janeiro

Courtesy Projeto Hélio Oiticica, Rio de Janeiro and Galerie Lelong, New York

Considered pioneers of the re-engagement of non-objective art, Josef Albers (1888-1976), Lygia Clark (1920-1988), and Hélio Oiticica (1937-1980) are represented by signature works. Albers’s Interlinear N 32 bl (1962) exemplifies his use of mechanical means to create a complex spatial illusion by engraving an impersonal, functional line within a field of hand-rolled jet black ink. Oiticica’s gouache Metaesquema 286 (1958) shows the effective use of simple, monochromatic shapes to create an active, open composition where the forms appear to pulsate across the plane, expanding the field in a rhythmic pattern that infers space beyond the paper’s borders. Clark’s Bicho (1960), made of folded aluminum, is from her well-known series that plays with notions of angled planes, active space, and the possibility of variable compositions and multiple vantage points contained within a single work.

Jo Baer (b.1929), Carmen Herrera (b. 1915), Robert Mangold (b.1937), and Sean Scully (b. 1945) further explore the potency of line and color. In Untitled (1972), Baer expands the stark white center of her composition, pushing thin bands of her distinctive black and blue hues to the very edges, to create a shift in the use of central space, characteristic of her minimal works of the 1970s. Herrera creates striking spatial tension by the precise placement of a thick graphic L-shaped black line that dissects a bold field of saturated green in Untitled (1976). More subtle in color and treatment of line, Mangold’s Four Triangles within a Square (Cream) (1976) conveys a sense of architectural drafting. Scully’s paintings also suggest built space, but through painterly brushstrokes that make up horizontal and vertical bands of subdued colors.

Catherine Lee (b. 1950), Sol LeWitt (1928-2007), Charlotte Posenenske (1930-1985), Liam Gillick (b. 1964), and Peter Halley’s (b. 1953) work involves serial, specific forms. Lee uses a grid to give her pastel drawings order, leaving her hand visible in each work in contrast to the purity LeWitt sought in his sculptures. LeWitt is represented by one of his open cube structures, a form he revisited throughout his career. Like LeWitt, Posenenske was interested in serialization and minimalism, as exemplified by her Series B Relief (blue reconstruction) (1967/2008-2011) consisting of three aluminum elements sprayed with industrial RAL paint. Gillick also uses RAL paint to uniformly coat sculptures, but deliberately makes relationships to functional structures as in Mean Completion (2008-2009). Halley uses the building construction paint additive Roll-a-Tex to create rough textures and a taut interplay of geometric forms, which he repeats in his work but with different compositions and colors.

Kate Shepherd (b. 1961), Sarah Crowner (b. 1974) and Tony Lewis (b. 1986) use a variety of visual references as a method of subversion. Shepherd’s interest in both traditional color theory models and value-based painting is apparent in her “triangle suit” series made with precisely cut screen prints. Tonal variations interlock to form an elongated triangular shape, stretched from the original Albers model, making them a more personal expression by the artist. Crowner, who is strongly influenced by Lygia Clark’s vibrant forms, sews together treated linen and canvas to create physically alluring surfaces. Lewis, the youngest artist in the exhibition, also divides his compositions but with a strong line, using pencil and graphite powder to create sooty surfaces reminiscent of the grit of the city, while maintaining a connection to the modernist grid.