The Blue Rider. A new language

12 Mar 2024 - 01 Dec 2025

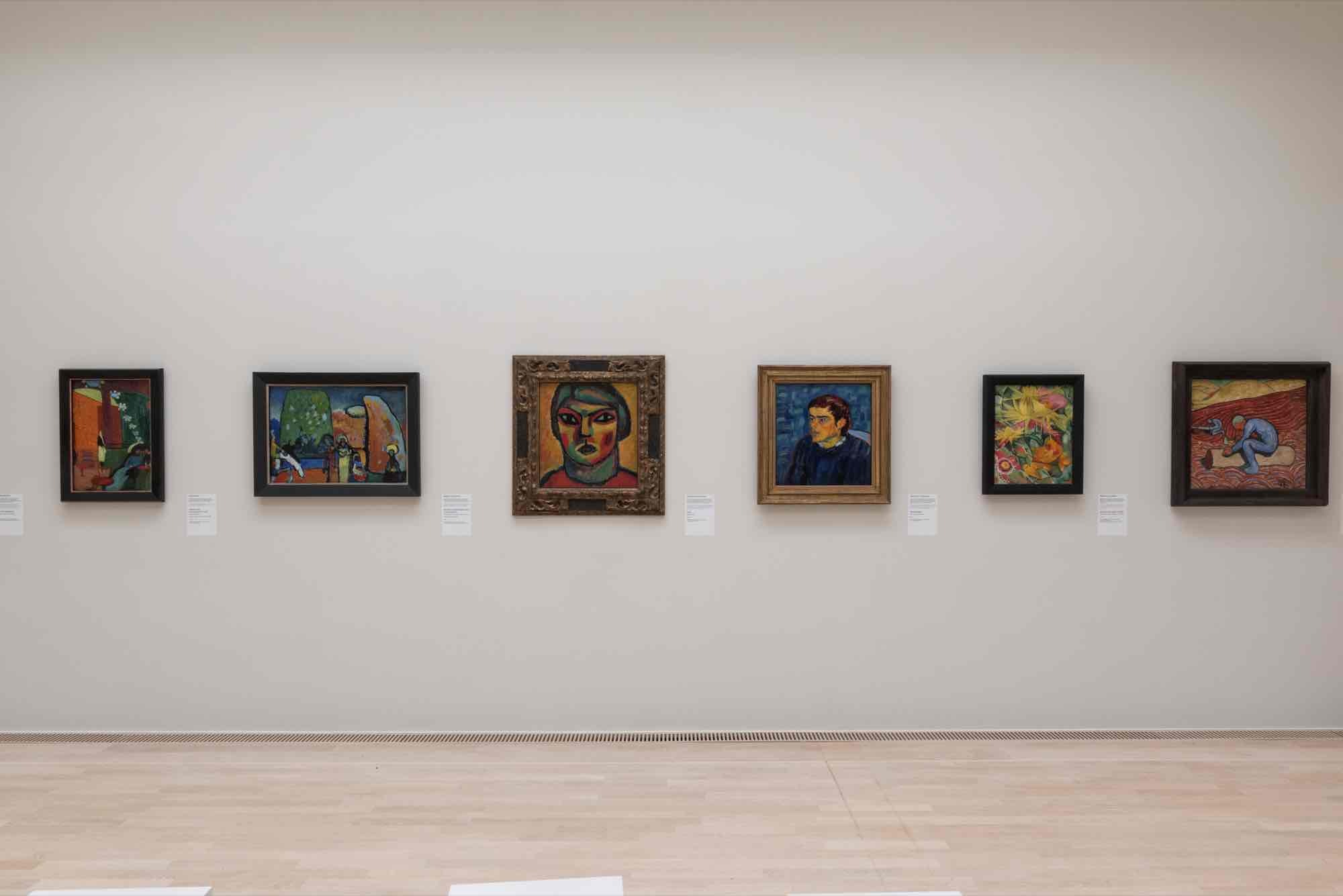

Installation Shot, The Blue Rider. A new language, Lenbachhaus, 2024. Photo: Lukas Schramm, Lenbachhau

Installation Shot, The Blue Rider. A new language, Lenbachhaus, 2024. Photo: Lukas Schramm, Lenbachhau

Installation Shot, The Blue Rider. A new language, Lenbachhaus, 2024. Photo: Lukas Schramm, Lenbachhau

Installation Shot, The Blue Rider. A new language, Lenbachhaus, 2024. Photo: Lukas Schramm, Lenbachhau

Installation Shot, The Blue Rider. A new language, Lenbachhaus, 2024. Photo: Lukas Schramm, Lenbachhau

Installation Shot, The Blue Rider. A new language, Lenbachhaus, 2024. Photo: Lukas Schramm, Lenbachhau

Installation Shot, The Blue Rider. A new language, Lenbachhaus, 2024. Photo: Lukas Schramm, Lenbachhau

Installation Shot, The Blue Rider. A new language, Lenbachhaus, 2024. Photo: Lukas Schramm, Lenbachhau

Installation Shot, The Blue Rider. A new language, Lenbachhaus, 2024. Photo: Lukas Schramm, Lenbachhau

Installation Shot, The Blue Rider. A new language, Lenbachhaus, 2024. Photo: Lukas Schramm, Lenbachhau

“The language of nature is different from the language of art. One cannot copy from one language into the other, only translate. Besides the literal and the loose translation, there is also the poetic adaptation, which has its own right.” (Gabriele Münter)

As part of the cooperation between the Lenbachhaus and Tate, the exhibition “Expressionists. Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider” to be held in London from April 25 until October 20 will showcase numerous works on loan from our collection. It is a unique opportunity for the Lenbachhaus, which boasts the largest collection of Blue Rider art in the world, to present highlights from our holdings that cannot travel together with works by the Blue Rider artists that have rarely been on display and to embed their oeuvres in a wider historical context.

One of the many Secessionist movements to emerge around 1900, the Blue Rider had roots that went back to Art Nouveau and Impressionism. The interest in folk art, children’s art, Japanese woodcuts, Bavarian reverse glass painting, and the international avant-gardes as well as the need for unconstrained creative development became mainsprings of the Blue Rider. The intense exchange of ideas between artists including Gabriele Münter, Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, Maria Franck-Marc, August Macke, Alexej Jawlensky, Marianne Werefkin, Robert Delaunay, and Elisabeth Epstein generated a productive group dynamic: the Blue Rider. Together, the artists now sought to forge a new language in art. Their quest was not for homogeneity of formal means, but for an expression of collective ideas: they aspired to articulate subjective experience, engage in dialogue across national borders, and devise a visual language for spiritual/intellectual truths. Those objectives find multifaceted realization in the works of the Blue Rider artists: from Kandinsky’s and Marc’s abstractions to Jawlensky’s, Münter’s, and Werefkin’s expressive depictions of humans and nature.

This development of a novel language is the focus of the new hanging, which also draws attention to the Blue Rider’s immediate antecedents as well as its afterlife: for instance, the work of the Art Nouveau artist Katharine Schäffner, who was active in Munich, among other places, around the turn of the century and whose dynamic prints anticipate abstraction, is an integral part of the group’s history, as are the carefully composed photographs that Gabriele Münter took during her trip to the United States and the pictures in which Adriaan Korteweg and Paul Klee pushed the ideas of the Blue Rider in new directions. The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 marks the end of the Blue Rider. Yet its protagonists’ visual idioms keep evolving during the years of war and exile. Münter’s and Epstein’s output, for example, constitutes a direct bridge from the Blue Rider to the New Objectivity, with which their later oeuvres will be associated.

As part of the new presentation, the museum installs a curated library and film screening area. The former gathers literature that speaks to discourses and concerns relevant to the Blue Rider, including theoretical writings on the idea of abstraction and its relation to what Kandinsky invoked as the “grand spiritual” element, but also questions of social history such as the Blue Rider’s interactions with “exoticism” and colonialism. Contemporary films—at the time, the young medium was likewise searching for its own innovative language, making it a formative influence on artists like Münter—round out the presentation.

With a selection of ca. 240 works, including paintings, graphic art, reverse glass paintings, photographs, and sculptures, the exhibition traces a history from the eventful and seminal years around 1900 to the mid-twentieth century. Many of these treasures, including works by Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky’s dynamic abstractions from 1914, have not been on display in many years. The presentation also brings the public début of recent acquisitions by the Friends of Lenbachhaus, among them works by Franz Marc, Maria Franck-Marc, and the artist Moissey Kogan, who was persecuted and murdered by the Nazis.

Curated by Melanie Vietmeier, Nicholas Maniu, and Matthias Mühling

As part of the cooperation between the Lenbachhaus and Tate, the exhibition “Expressionists. Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider” to be held in London from April 25 until October 20 will showcase numerous works on loan from our collection. It is a unique opportunity for the Lenbachhaus, which boasts the largest collection of Blue Rider art in the world, to present highlights from our holdings that cannot travel together with works by the Blue Rider artists that have rarely been on display and to embed their oeuvres in a wider historical context.

One of the many Secessionist movements to emerge around 1900, the Blue Rider had roots that went back to Art Nouveau and Impressionism. The interest in folk art, children’s art, Japanese woodcuts, Bavarian reverse glass painting, and the international avant-gardes as well as the need for unconstrained creative development became mainsprings of the Blue Rider. The intense exchange of ideas between artists including Gabriele Münter, Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, Maria Franck-Marc, August Macke, Alexej Jawlensky, Marianne Werefkin, Robert Delaunay, and Elisabeth Epstein generated a productive group dynamic: the Blue Rider. Together, the artists now sought to forge a new language in art. Their quest was not for homogeneity of formal means, but for an expression of collective ideas: they aspired to articulate subjective experience, engage in dialogue across national borders, and devise a visual language for spiritual/intellectual truths. Those objectives find multifaceted realization in the works of the Blue Rider artists: from Kandinsky’s and Marc’s abstractions to Jawlensky’s, Münter’s, and Werefkin’s expressive depictions of humans and nature.

This development of a novel language is the focus of the new hanging, which also draws attention to the Blue Rider’s immediate antecedents as well as its afterlife: for instance, the work of the Art Nouveau artist Katharine Schäffner, who was active in Munich, among other places, around the turn of the century and whose dynamic prints anticipate abstraction, is an integral part of the group’s history, as are the carefully composed photographs that Gabriele Münter took during her trip to the United States and the pictures in which Adriaan Korteweg and Paul Klee pushed the ideas of the Blue Rider in new directions. The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 marks the end of the Blue Rider. Yet its protagonists’ visual idioms keep evolving during the years of war and exile. Münter’s and Epstein’s output, for example, constitutes a direct bridge from the Blue Rider to the New Objectivity, with which their later oeuvres will be associated.

As part of the new presentation, the museum installs a curated library and film screening area. The former gathers literature that speaks to discourses and concerns relevant to the Blue Rider, including theoretical writings on the idea of abstraction and its relation to what Kandinsky invoked as the “grand spiritual” element, but also questions of social history such as the Blue Rider’s interactions with “exoticism” and colonialism. Contemporary films—at the time, the young medium was likewise searching for its own innovative language, making it a formative influence on artists like Münter—round out the presentation.

With a selection of ca. 240 works, including paintings, graphic art, reverse glass paintings, photographs, and sculptures, the exhibition traces a history from the eventful and seminal years around 1900 to the mid-twentieth century. Many of these treasures, including works by Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky’s dynamic abstractions from 1914, have not been on display in many years. The presentation also brings the public début of recent acquisitions by the Friends of Lenbachhaus, among them works by Franz Marc, Maria Franck-Marc, and the artist Moissey Kogan, who was persecuted and murdered by the Nazis.

Curated by Melanie Vietmeier, Nicholas Maniu, and Matthias Mühling