Nasrin Tabatabai and Babak Afrassiabi

27 Oct 2012 - 20 Jan 2013

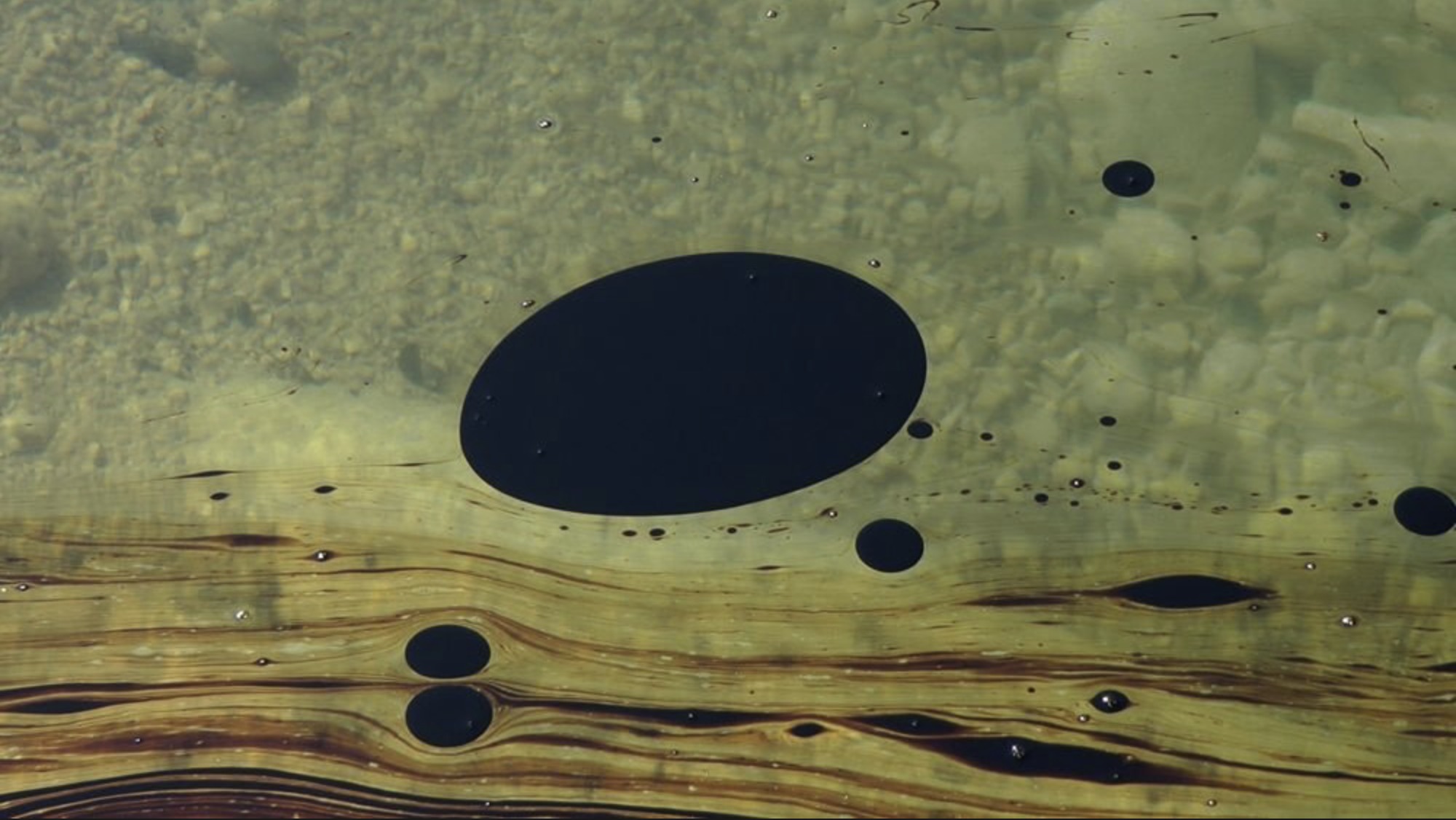

Nasrin Tabatabai & Babak Afrassiabi, Seep (2) (Viatge al sud-oest de l'Iran), 2012. MACBA Collection. MACBA Foundation. Produced by MACBA Foundation. © Nasrin Tabatabai i Babak Afrassiabi, 2020.

NASRIN TABATABAI AND BABAK AFRASSIABI

Seep

27 October 2012 - 20 January 2013

Nasrin Tabatabai and Babak Afrassiabi have been collaborating together under the name Pages since 2004, involving various joint projects and the publication of a bilingual magazine in Farsi and English. They are based in Rotterdam and work both in Iran and the Netherlands. Their projects and the magazine's editorial approach are closely linked, often founded on the historically and politically equivocal relationships between modernity and contemporary art.

In their first solo exhibition in Spain, and as a result of their collaboration with MACBA, Tabatabai and Afrassiabi present the installation Seep. The exhibition includes two video projections, a model, a series of objects and associated images largely inspired by archival materials preserved in two institutions in the UK and Iran: the archive of British Petroleum (BP) and the Western collection of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art.

In 2011, Tabatabai and Afrassiabi began a series of works that take as their point of departure two archives/collections of the twentieth century. One is the archive of British Petroleum (BP) related to the company's origin in Iran between 1901 and 1951, when it operated under the name of the Anglo Iranian Oil Company (AIOC) and found the first oil in the Middle East. This archive is comprised of detailed photographic, textual and filmic documentation since the beginning of the twentieth century – from the early searches for oil to the building of one of the world's biggest oil refineries and the city of Abadan, which became a model modern industrial city in the Middle East. This section of the BP archive is not only a meticulous registration of the company's development and growth in Iran but also a story of modernisation and modernity. However, by 1951 the workers' strikes, political demonstrations and the pursuit of the nationalisation of oil by Mohammad Mosaddegh, the newly elected popular prime minister in Iran, put the refinery on hold and forced the evacuation of the British from the country.

The other archive belongs to a quarter of a century later: the collection of Western art from late nineteenth century to the late 1970s in the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art (TMOCA). The market crisis and the increase in oil prices during the 1970s, which had resulted in an economic boom in Iran, made possible the rapid building of a large collection of European and American art. The collection was acquired parallel to the building of the museum in a period of only a few years and was inaugurated in October 1977 together with the museum as part of the government's rapid modernisation project. After the Islamic Revolution in Iran in 1979, the collection was renounced and withdrawn to the museum'scellars, and it was only twenty years later that a careful selection of it was again publicly exhibited.

One thing these two archives have in common is their eventual suspension. And it is precisely in such a state of discontinuation (as in the case of the BP archive) or removal (as with the collection of TMOCA) that Tabatabai and Afrassiabi locate these two archives through their works. This, of course, proposes a subtractive notion of the archive, one that reconsiders the archive in its impossibility and irresoluteness.

Seep, the installation that is currently exhibited at MACBA, is entirely comprised of new works related to these two archives. All works are presented alongside each other, with each part loosely alluding to the other. One of the central pieces in the installation is the projection of a 6-minute video. A male voice (of a film director) reads a letter (dated 11 March 1951) about the 'unfilmability' of a 'worthwhile Technicolor film in the oil fields and Abadan'. In close-up takes, the camera moves through a theatrical set over various objects. Twice the video is cut to an overall shot of the set in the form of a silhouette on a projection screen. This is coupled with pre-recorded shots of a hand going through a series of black-and-white photographs of what could be the location of the film in question: the oil fields and the city of Abadan in Iran. Next to this video is a series of printed correspondence between the film director and the oil company's various authorities involved in the making of the same Technicolor film. From these letters, we detect that in 1951 the Anglo Iranian Oil Company had commissioned Ralph Keen, a director, to make an overall narrative film about Iran's ancient cultural heritage and the oil industry's positive effects on the modernisation of Iran and Iranian citizens. The film would be called Persian Story. However, the various practical obstacles faced by the director had forced him to consider abandoning the entire project. In the end only a short colour film was made, limited to the oil company and its amenities.

The focus on the film Persian Story in the installation is in fact an emphasis on the 'unfilmability' of the archive itself. The film was an unsuccessful final attempt to produce a seamless Technicolor story in accordance with the narrative of modernisation that the archive had been projecting since coming into existence. And it is out of this 'unfulfilled fiction' that the artists identify the possibility of another kind of archive of modernity.

Parallel to the mentioned video, the installation incorporates a further video projection documenting the artists' visit to the southwest of Iran and to some of the sites of the BP archive, but specifically in search of oil seeps oozing out from under the ground and floating over water. Having a wholly different temporality to the archive, and almost a disregard for history, the oil seepage was curiously one of the objects that remained 'unfilmable' for Persian Story.

The installation also includes a sculptural model of the building of the TMOCA. This is not a strict one-to-one depiction of the museum building. Rather, the model focuses on the interior passages, which begin on the ground floor and descend to the lower levels. The actual museum has only one floor above ground, with its galleries, offices and museum depot located on the lower floors.

Although the Western collection of the museum has come to embody a historically and culturally misplaced and disputed experience with modernity and modern art, is a historical disposition still imaginable from this? This is one of the questions posed by the installation Seep. When acquired, the collection was supposed to fulfil the desired association with the West and to generate a sense of contemporariness in 1970s Iran. But this pursuit of contemporariness carried a deep denial of the collection's immediate socio-political and historical conditions. In other words, the collection – a stranger in a foreign land – became truly contemporary only when it was withdrawn into the museum's cellar, and so re-entered history albeit through an inverse route.

Seep

27 October 2012 - 20 January 2013

Nasrin Tabatabai and Babak Afrassiabi have been collaborating together under the name Pages since 2004, involving various joint projects and the publication of a bilingual magazine in Farsi and English. They are based in Rotterdam and work both in Iran and the Netherlands. Their projects and the magazine's editorial approach are closely linked, often founded on the historically and politically equivocal relationships between modernity and contemporary art.

In their first solo exhibition in Spain, and as a result of their collaboration with MACBA, Tabatabai and Afrassiabi present the installation Seep. The exhibition includes two video projections, a model, a series of objects and associated images largely inspired by archival materials preserved in two institutions in the UK and Iran: the archive of British Petroleum (BP) and the Western collection of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art.

In 2011, Tabatabai and Afrassiabi began a series of works that take as their point of departure two archives/collections of the twentieth century. One is the archive of British Petroleum (BP) related to the company's origin in Iran between 1901 and 1951, when it operated under the name of the Anglo Iranian Oil Company (AIOC) and found the first oil in the Middle East. This archive is comprised of detailed photographic, textual and filmic documentation since the beginning of the twentieth century – from the early searches for oil to the building of one of the world's biggest oil refineries and the city of Abadan, which became a model modern industrial city in the Middle East. This section of the BP archive is not only a meticulous registration of the company's development and growth in Iran but also a story of modernisation and modernity. However, by 1951 the workers' strikes, political demonstrations and the pursuit of the nationalisation of oil by Mohammad Mosaddegh, the newly elected popular prime minister in Iran, put the refinery on hold and forced the evacuation of the British from the country.

The other archive belongs to a quarter of a century later: the collection of Western art from late nineteenth century to the late 1970s in the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art (TMOCA). The market crisis and the increase in oil prices during the 1970s, which had resulted in an economic boom in Iran, made possible the rapid building of a large collection of European and American art. The collection was acquired parallel to the building of the museum in a period of only a few years and was inaugurated in October 1977 together with the museum as part of the government's rapid modernisation project. After the Islamic Revolution in Iran in 1979, the collection was renounced and withdrawn to the museum'scellars, and it was only twenty years later that a careful selection of it was again publicly exhibited.

One thing these two archives have in common is their eventual suspension. And it is precisely in such a state of discontinuation (as in the case of the BP archive) or removal (as with the collection of TMOCA) that Tabatabai and Afrassiabi locate these two archives through their works. This, of course, proposes a subtractive notion of the archive, one that reconsiders the archive in its impossibility and irresoluteness.

Seep, the installation that is currently exhibited at MACBA, is entirely comprised of new works related to these two archives. All works are presented alongside each other, with each part loosely alluding to the other. One of the central pieces in the installation is the projection of a 6-minute video. A male voice (of a film director) reads a letter (dated 11 March 1951) about the 'unfilmability' of a 'worthwhile Technicolor film in the oil fields and Abadan'. In close-up takes, the camera moves through a theatrical set over various objects. Twice the video is cut to an overall shot of the set in the form of a silhouette on a projection screen. This is coupled with pre-recorded shots of a hand going through a series of black-and-white photographs of what could be the location of the film in question: the oil fields and the city of Abadan in Iran. Next to this video is a series of printed correspondence between the film director and the oil company's various authorities involved in the making of the same Technicolor film. From these letters, we detect that in 1951 the Anglo Iranian Oil Company had commissioned Ralph Keen, a director, to make an overall narrative film about Iran's ancient cultural heritage and the oil industry's positive effects on the modernisation of Iran and Iranian citizens. The film would be called Persian Story. However, the various practical obstacles faced by the director had forced him to consider abandoning the entire project. In the end only a short colour film was made, limited to the oil company and its amenities.

The focus on the film Persian Story in the installation is in fact an emphasis on the 'unfilmability' of the archive itself. The film was an unsuccessful final attempt to produce a seamless Technicolor story in accordance with the narrative of modernisation that the archive had been projecting since coming into existence. And it is out of this 'unfulfilled fiction' that the artists identify the possibility of another kind of archive of modernity.

Parallel to the mentioned video, the installation incorporates a further video projection documenting the artists' visit to the southwest of Iran and to some of the sites of the BP archive, but specifically in search of oil seeps oozing out from under the ground and floating over water. Having a wholly different temporality to the archive, and almost a disregard for history, the oil seepage was curiously one of the objects that remained 'unfilmable' for Persian Story.

The installation also includes a sculptural model of the building of the TMOCA. This is not a strict one-to-one depiction of the museum building. Rather, the model focuses on the interior passages, which begin on the ground floor and descend to the lower levels. The actual museum has only one floor above ground, with its galleries, offices and museum depot located on the lower floors.

Although the Western collection of the museum has come to embody a historically and culturally misplaced and disputed experience with modernity and modern art, is a historical disposition still imaginable from this? This is one of the questions posed by the installation Seep. When acquired, the collection was supposed to fulfil the desired association with the West and to generate a sense of contemporariness in 1970s Iran. But this pursuit of contemporariness carried a deep denial of the collection's immediate socio-political and historical conditions. In other words, the collection – a stranger in a foreign land – became truly contemporary only when it was withdrawn into the museum's cellar, and so re-entered history albeit through an inverse route.