Alighiero Boetti

20 Feb - 05 May 2013

ALIGHIERO BOETTI

Il Muro et autres œuvres

20 February - 5 May 2013

In 1973 Alighiero Boetti began hanging pictures, drawings of friends, photographs, calendar pages and found objects on a wall of his apartment in Rome’s Trastevere district. Over the years this domestic ‘work in progress’, which he took with him wherever he lived, became Il Muro (The Wall) — a kind of personal poetic constellation, a metaphor for a human journey, an intimate place for reflection on the world.

With its unusual combination of a poem, a parchment, a Persian screen print, a photograph of his son in Kabul, a sketch, a calligraphy, a note, a collage by his daughter, a letter, a page from a diary, The Wall is a series of encounters — contagious contacts that can yield unexpected meanings. The positions of the items in the constellation varied, some becoming central, others being relegated to the periphery or in some cases becoming works in their own right.

Alighiero Boetti always called himself a painter, even though at the age of 22 he gave up painting to make greater use of other techniques and materials (collage, spray painting, stencilling, stamping, decalcomania, frottage, calligraphy and so on). Having embarked on his artistic career in Turin in the mid-1960s as part of the Arte Povera movement, he soon parted company with it, even though he had been one of its leading proponents: ‘We’d gone too far in our focus on materials ... we were getting to be more like druggists than artists. That’s why I quit my studio in 1969 ... I left it all behind, and started from scratch with a pencil and a sheet of paper. The result was called Il cimento dell’armonia e dell’invenzione [‘The endeavour of harmony and invention’]. It was made up of small squares. That’s what starting all over again meant to me.’ Henceforth a major medium in his work, sheets of (often squared) paper allowed him to develop all kinds of visual conceptual processes, from simple geometric forms to exploration of language.

Boetti’s interest in linguistic form was never exhausted, whether it was letters, words, figures, numbers, sentences, codes or dates he was dealing with. Words, and their alpha- betical configuration, had a poetic potential that Boetti explored by envisaging every possible way of transcrib- ing them: choosing a word and redistributing its letters in alphabetical order, phonetically transcribing a word spelled in Italian, suggesting a word by means of commas arranged according to invisible coordinates, one being the alpha- bet, the other the direction of reading. The words became abstract images through the interplay of commas, each of which stood for a letter. These ballpoint calligraphies on paper, doodles which Boetti delegated to often anonymous artists, caused signs to emerge in white against a coloured — black, blue, red or green — background. Another way of exploring language, for which Boetti preferred coloured embroidery to paper, was to insert words in a square grid. In Ordine e disordine (‘Order and Disorder’ 1973), the words were inscribed on a hundred square embroideries, all of them divided into sixteen sections containing just one letter each. This ‘order’ was contradicted by the permutations of the sixteen letters on each embroidery.

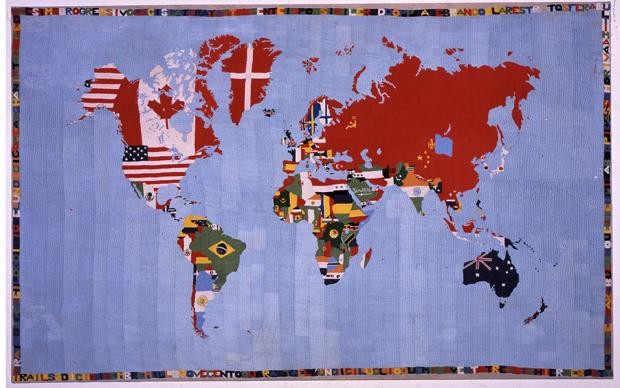

During his second trip to Kabul in 1971, the nomadically-minded Boetti had his first Mappa — a map on which the territories of the various countries were filled with the coloured patterns of their national flags — produced by Afghan embroiderers. Over the next twenty years more than a hundred and fifty Mappe, in a variety of colours and sizes, were embroidered on the basis of his drawings, shaping his image of the world and showing the passage of time and the political changes that were taking place. The Mappa on show at Mamco is one of the first produced in Kabul, between 1971 and 1973.

The exhibition includes Boetti’s set of drums. Coming from a family that listened to and played music, Boetti – although he never became the conductor he had dreamed of being as a child – played drums, because ‘the drum is the only instrument used by shamans and “medicine men” all over the world, because its rhythms can put you into a trance. Sometimes when you’re playing you find yourself levitating a metre off the ground.’

Alighiero Boetti was born in Turin in 1940, and died in Rome in 1994.

Il Muro et autres œuvres

20 February - 5 May 2013

In 1973 Alighiero Boetti began hanging pictures, drawings of friends, photographs, calendar pages and found objects on a wall of his apartment in Rome’s Trastevere district. Over the years this domestic ‘work in progress’, which he took with him wherever he lived, became Il Muro (The Wall) — a kind of personal poetic constellation, a metaphor for a human journey, an intimate place for reflection on the world.

With its unusual combination of a poem, a parchment, a Persian screen print, a photograph of his son in Kabul, a sketch, a calligraphy, a note, a collage by his daughter, a letter, a page from a diary, The Wall is a series of encounters — contagious contacts that can yield unexpected meanings. The positions of the items in the constellation varied, some becoming central, others being relegated to the periphery or in some cases becoming works in their own right.

Alighiero Boetti always called himself a painter, even though at the age of 22 he gave up painting to make greater use of other techniques and materials (collage, spray painting, stencilling, stamping, decalcomania, frottage, calligraphy and so on). Having embarked on his artistic career in Turin in the mid-1960s as part of the Arte Povera movement, he soon parted company with it, even though he had been one of its leading proponents: ‘We’d gone too far in our focus on materials ... we were getting to be more like druggists than artists. That’s why I quit my studio in 1969 ... I left it all behind, and started from scratch with a pencil and a sheet of paper. The result was called Il cimento dell’armonia e dell’invenzione [‘The endeavour of harmony and invention’]. It was made up of small squares. That’s what starting all over again meant to me.’ Henceforth a major medium in his work, sheets of (often squared) paper allowed him to develop all kinds of visual conceptual processes, from simple geometric forms to exploration of language.

Boetti’s interest in linguistic form was never exhausted, whether it was letters, words, figures, numbers, sentences, codes or dates he was dealing with. Words, and their alpha- betical configuration, had a poetic potential that Boetti explored by envisaging every possible way of transcrib- ing them: choosing a word and redistributing its letters in alphabetical order, phonetically transcribing a word spelled in Italian, suggesting a word by means of commas arranged according to invisible coordinates, one being the alpha- bet, the other the direction of reading. The words became abstract images through the interplay of commas, each of which stood for a letter. These ballpoint calligraphies on paper, doodles which Boetti delegated to often anonymous artists, caused signs to emerge in white against a coloured — black, blue, red or green — background. Another way of exploring language, for which Boetti preferred coloured embroidery to paper, was to insert words in a square grid. In Ordine e disordine (‘Order and Disorder’ 1973), the words were inscribed on a hundred square embroideries, all of them divided into sixteen sections containing just one letter each. This ‘order’ was contradicted by the permutations of the sixteen letters on each embroidery.

During his second trip to Kabul in 1971, the nomadically-minded Boetti had his first Mappa — a map on which the territories of the various countries were filled with the coloured patterns of their national flags — produced by Afghan embroiderers. Over the next twenty years more than a hundred and fifty Mappe, in a variety of colours and sizes, were embroidered on the basis of his drawings, shaping his image of the world and showing the passage of time and the political changes that were taking place. The Mappa on show at Mamco is one of the first produced in Kabul, between 1971 and 1973.

The exhibition includes Boetti’s set of drums. Coming from a family that listened to and played music, Boetti – although he never became the conductor he had dreamed of being as a child – played drums, because ‘the drum is the only instrument used by shamans and “medicine men” all over the world, because its rhythms can put you into a trance. Sometimes when you’re playing you find yourself levitating a metre off the ground.’

Alighiero Boetti was born in Turin in 1940, and died in Rome in 1994.