9TH LECTURE AT THE GRAMSCI MONUMENT, THE BRONX, NYC: 9TH JULY 2013 ON ADORNO MARCUS STEINWEG

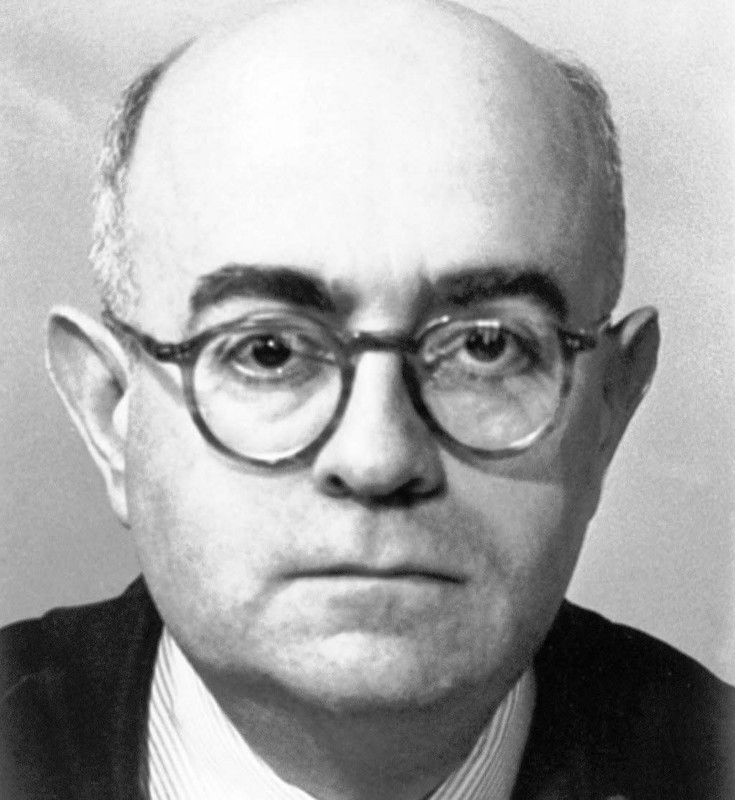

Theodor W. Adorno

In a letter to Thomas Mann dated August 1, 1950, Theodor W. Adorno—anticipating his conception of negative dialectics—described the “writer’s dilemma” in words that apply to the dilemma of art in general: “One either defers to the tact of language, which almost inevitably involves a loss of precision in the matter, or one privileges the latter over the former and thereby does violence to language itself. Every sentence is effectively an aporia, and every successful utterance a happy deliverance, a realization of the impossible, a reconciliation of subjective intention with objective spirit, whereas the essence consists precisely in the diremption of both.” In Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory, virtually every sentence is an articulation by linguistic means of the aporetic essence of art. The challenge is to lend expression to “the constitutive relation of art to what it itself is not, to what is not the pure spontaneity of the subject.” The ambiguity of the work of art becomes apparent once again, its ambivalence between the desire for reconciliation and its implacable irreconcilability: art as what oscillates between identity and difference, between form and formlessness. It is this in-between that defines the status of the artist’s assertion of form as the form of the formless as much as the formlessness of form. To steer clear of the pitfall of aestheticism, art must acknowledge its self-extension into the non-artistic sphere of fact. On the other hand, in order to avoid becoming an instrument in the image of socio-political commitment or by moralizing, it insists on aesthetic autonomy. Instead of choosing between violence and nonviolence, art votes for itself as the operator of this in-between that can hardly be conciliated in a speculative synthesis. Any assertion of form mediates itself to its (social) other because this other has long leapt ahead of it. And yet art must not amount to no more than worship of the other or the incommensurable, for that way lies the sacrifice of its capacity of form to the religious sentiment of formlessness. Art is what bears, and articulates, the antagonism of form and formlessness.

There is an irreconcilable difference between art and culture, and so art must needs defend itself against culture and its imperatives. He is an artist who engenders a conception of art that has never yet existed in this precise form. The only works of art that count are those that, rather than inscribing themselves upon an instituted conception of art, generate a conception to oppose it. The task is always to open up, in the dynamism of production, toward an as yet indeterminate conception of art; it is never the execution of a program that takes its orientation from fixed norms. “In truth,” Adorno says, works of art are “force fields that enact the conflict between the norm imposed upon them and that which seeks expression in them. The higher they rank, the more energetically do they fight this conflict out, often renouncing affirmative accomplishment.” The work of art articulates the conflict between what already exists and the new such that the work appears as the stage of an enactment of difference in which the established conception of art encounters an objection. At the same time, we must understand that a clear separation between what exists and the new remains a challenge that cannot be met: “Even the category of the new, which in the artwork represents what has yet to exist and that whereby the work transcends the given, bears the scar of the ever-same underneath the constantly new. Consciousness, fettered to this day, has not gained mastery over the new, not even in the image: Consciousness dreams of the new but is not able to dream the new itself.” The work of art draws its power from its resistance against forces that reduce it to an effect of what already exists. The affirmative aspect of the work consists in its being open toward something beyond what already exists, something whose positivity it first generates. The experience of art is the experience of the conditions of its possibility as much as of the affront to these conditions the work represents. The concept of art condenses the paradox of a performance that must turn against its own possibilities for the sake of the impossible as the impossible that is possible within its realm. Art is what engenders a conception of art in the assertion of works that, as they resist assimilation to what already exists, articulate themselves as affirmations of contingency, as figures of an opening toward an indeterminate or incommensurable something that marks the truth of the space of fact. I call the universe of fact the dimension of a reality overdetermined by social, political, economic, historical, cultural, biological, technological, etc. factors. It is here that the work of art fights for its autonomy, in the field of factual codification and real heteronomy—a heteronomy the work remains at risk of falling back into—: “Artworks are able to appropriate their heterogeneous element, their entwinement with society, because they are themselves always at the same time something social. Nevertheless, art’s autonomy, wrested painfully from society as well as socially derived in itself, has the potential of reversing into heteronomy; everything new is weaker than the accumulated ever-same, and it is ready to regress back into it.”

Art “refuses definition,” but it equally calls for one. Art hardly exists other than as the work on its concept, the work of determining what art is and ought to be. In opening up toward what it has long been embedded in, the dimension of constituted certainties and valencies, art urges toward the boundaries of the space of fact as much as that of its own concept and its previous manifestations. Part and parcel of art is a dynamism of its bringing itself forth through the works, the ongoing redefinition of what its concept encompasses. Art expands the concept of art by blurring the boundaries that separate it from its other, from what delimits it. Every work of art is a form of boundary-blurring, an excess directed at its implicit inconsistency; an excess that marks the blurring of its boundary toward its boundary, its being-open to the formlessness whose medium it remains. Art is an assertion of form that engenders itself in an opening toward the formless. Be such formlessness that of society, as an excessively complex and internally contradictory space of fact—the zone of socio-historico-symbolic evidence—be it the point of inconsistency of this domain, the incommensurability commensurable to it.

The affirmation of the work of art is the affirmation of its polemic violence, which turns against everything that constrains its aspiration to autonomy: the constituted reality in its complexity and variety, what Adorno calls society. There is art only in the here and now of the one world without exit: the world of fact. Art is not an escape from it; it frames its aspiration to autonomy amid the world of determiners in order to escape in an opening toward heteronomy its phantasmatic failure to coincide with itself. Just as freedom exists only under the conditions of de facto unfreedom and self-possession only under those of its absence, autonomy becomes a demand and a necessity only in the field of de facto heteronomy. Adorno never ceases to insist on the possibility of aesthetic autonomy in its opening toward its own impossibility. This renders him the advocate of a possible impossibility. Part and parcel of art is its “rejection of empirical reality.” Art departs the “empirical world” not by fleeing into a second, a higher world but by intensifying its relation to this one. The “affirmative essence” of art must turn against its own distorted image, against the idealist temptation to locate art somewhere beyond the world of fact. Affirmation is not naïveté or approbation. Affirmation is invention and construction. The affirmative intensity of the work of art includes a double gesture that encompasses the acknowledgment of its historicity as much as the courage to forgo self-satisfied self-enclosure in a critical-reflective assurance of its status as a resultant, a double gesture that demands an opening toward the inconsistency in the fabric of determiners. Facts are nothing but facts, states of affairs only states of affairs: art knows that knowledge is not everything, that the artist’s responsibility begins with building affirmative resistance to all vulgar materialisms and positivisms while also suspending all idealisms that promise to it the existence of a reality beyond this, the only one; for that way lies its total dehistoricization. Realism or idealism: the alternative is deceptive—in the history of philosophy, in philosophical aesthetics, in art.

A “concept of history [...] as a critique of philosophy” that “does not seek to abandon philosophy itself,” as Adorno and Horkheimer write in the preface to the second edition of their Dialectics of the Enlightenment, has its counterpart in the effort “to transcend the concept” “by way of the concept,” as well as in a conception of art that, in the face of its impossibility (heteronomy, historicity), gains insight into its possibility (autonomy, universality). What holds for the concept of a true human being also holds for the true work of art: “He would be neither a mere function of a whole, which is inflicted upon him so thoroughly that he cannot distinguish himself from it anymore, nor would he simply retrench himself in his pure selfhood.” It is amid this tension between immanence and transcendence that the concept of art has its place as much as that of the subject: porous toward the totality of social fact as well as its inconsistency, for to touch this inconsistency is to seize the possibility of autonomy and freedom. This is the affirmation the work of art performs, the acknowledgment of itself as an element of the empirical world as much as the figure of an opposition resistant to it.

The work of art stands its ground amid a world to which it cannot assimilate. The act of creatio is not so much a heroic act as one of embarrassment. “Go with art into your very own narrowness. And set yourself free”: the sentence from Paul Celan’s Meridian speech articulates this, if we may say so, encouraging embarrassment. It is indispensable that we tie the work of art to the category of courage; but the courage whose manifestation is the work is not the courage of a subject that remains within the field of its possibilities. This subject would already be discouraged, for it knows nothing but possibilities, nothing but options, nothing but realities, nothing but freedoms that are none. The freedom of setting-oneself-free of which Celan speaks is a different one. It is the freedom of a subject that does not know absolute freedom; freedom in the objective unfreedom of freedoms on offer and sold, by the power of fact, as alternatives. To go into one’s very own narrowness means to resist these alternatives, to seek out the utmost recess of one’s possibilities, the edge of the zone of fact; and to see here, touching upon the wall of the impossible, nothing more than this wall, this narrowness. Only here, in the experience of this blindness and narrowness, can something like a setting-oneself-free take place, in a transcendence of optional freedoms toward the freedom of the blind assertion of form. The assertion of form that is the work of art is an expression of affirmative resistance. It is affirmative to the extent that it acknowledges the limitations of the world of fact, including its imperatives of freedom; but it refuses to sacrifice to this acknowledgment the freedom of an assertion of form that remains an act of embarrassment. The world as it is cannot but daunt and embarrass. It reduces its subjects to operators in an already decided space of fact. Yet this reduction, which is unacceptable to any subject that asserts and maintains its subjecthood, generates energies of resistance, of embarrassment and aporia. We might describe the aporia within the established paths, the embarrassment in which the subject experiences the limitations of the real, as a critical element. Inherent to it, at least, is the possibility of stepping outside the field of reductive facts. As soon as there is embarrassment, there is something like dissatisfaction with the organization of the real, with the picture the world forms of itself. The subject of art is embarrassed also because this picture itself lacks all embarrassment, because it denies the possibility of being embarrassed, believing in itself as though in a matter of fact. What becomes apparent in embarrassment is the difference between fact and truth in all its irreconcilability. Facts are nothing but facts, while truths remain stopgaps born of embarrassment, born of the subject’s unwillingness to come to an arrangement with the facts. Here lies the resistance of the work of art: in its refusal to sacrifice to the powers of fact its embarrassment over their faith in themselves.

Art was never anything but acquiescence to the fragility of its time. Art does not emerge from a stable situation; it is the experience of the inconsistency of its reality. Art exists only as the experience that the system of fact has holes. That is why there cannot be for art an alliance with the facts, which is not to say that it denies or fails to apprehend their power. Only it amounts to more than the demonstration of this non-misapprehension, more than the analytical force that is also part of it. As long as art does not transcend its knowledge, it is not art. It would be nothing but self-assurance on the part of the subject within the fabric of a critical commentary on its situation. Only with the assertion of form that eludes narcissistic self-assurance by articulating the transitoriness of the certainties of fact does art succeed in confronting the universal inconsistency that is the subject’s true time and its true place. Rather than being a document of its time, the work of art is the corruption of the zeitgeist as much as the historico-social texture from which it nonetheless emerges. A work that would be nothing but the result of its conditions, reducible to its determiners, would not be a work. It remains the distinguishing mark of the work of art that it inscribes a resistance into the reality of which it is part by appearing within it as incommensurable to it. What distances it from the document is this excess that alienates it from its factuality, by indicating the ontological fragility of the texture of fact. The assertion of form on the part of the work of art neither denies its origins nor its existence in the world of fact; it simply resists being reduced to it by appearing within it as something unforeseen. The appearance of the work proves it to be the site of an antagonism between what already is and what threatens to topple it. Whereas the document by definition transmits, communicates, and archives information, the work of art is the act of calling information, communication, and archiving into question. The insistence “that the arts cannot be subsumed under an unbroken identity of art” indicates, first and foremost, that such an unbroken identity does not exist. By practicing the permanent re-destabilization of all forms and concepts, art compels the formation of an individual concept adequate to each work, a concept whose generality finds its corrective in the singularity of the individual work while gesturing beyond it toward its universality.