30TH LECTURE AT THE GRAMSCI MONUMENT, THE BRONX, NYC: 30TH JULY 2013 WHAT IS A PROBLEM? MARCUS STEINWEG

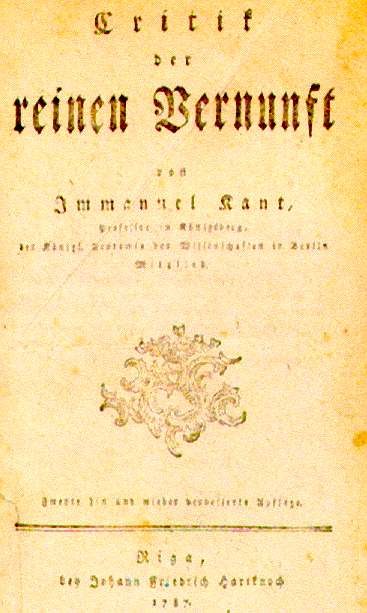

Immanuel Kant

A problematic statement and a problematic concept move along the watershed between what is and what is not, between presence and absence. "I call a concept problematic which contains no contradiction and also hangs together with other knowledge as a limitation of given concepts, but whose objective reality cannot be recognized in any way", Immanuel Kant writes. Kant's example for such a problematic concept is of course the Ding an sich, the thing in itself. "The concept of a noumenon, i.e. of a thing which is supposed to be thought not at all as an object of the senses, but as a Ding an sich merely by pure understanding, is not at all contradictory because it cannot be maintained that sensuousness is the only possible kind of intuition. Furthermore, this concept is necessary in order not to extend sensuous intuition over things in themselves and thus, in order to restrict the objective validity of sensuous knowledge, (for the rest, to which sensuous intuition does not reach, are called noumena precisely because with them one indicates that this knowledge cannot extend its territory over everything that understanding can think). [...] The concept of a noumenon is therefore merely a limiting concept in order to restrict the pretensions of sensuousness and is therefore only of negative use." The negative use of the concept of noumenon has the function of curtailing the over-extension of sensuousness to intelligibility, which also means drawing a limit between the order of space-time and the zone X which is the world or the non-world of the noumena.

It is indispensable to know that this limit is itself already problematic because, beyond the world of the phenomena, no second, in some sense higher world begins, for instance, in the shape of a factually existing realm of ideas. To open the subject to the noumenon does not mean to promise it another world. On the contrary, it means to orient it toward its world, the one and only, to confront it in the here-and-now of its space-time immanence with the radical limitedness of its order which is the universe of finitude. But this confrontation with the familiar universe demands at the same time the opening up of human subjectivity to the domain of an unfamiliarity which is the domain of the Ding an sich. Raised to an ontological level, the thing in itself is not simply the negative side of the phenomenon. Rather, it indicates the efficiency of an element 'present' only in the mode of absence which, by marking something beyond the sphere of phenomena, indicates the coincidence of this beyond with the limit itself. Accordingly, already Kantian thinking can be understood as a thinking of immanence because it radically contests the positivity of the nonetheless efficient noumenon.

From here, a relationship between Kant's thinking and Blanchot's can be established. The step or transgression to the noumenon is equally unavoidable (it has always already taken place) as it is impossible (because it has long since taken place and in this sense cannot be caught up with). It is a pas au-delà, a non-step into nothingness. It opens up the problematic or simply paradoxical thinking of a relation without relation (rapport sans rapport) which characterizes perhaps the most general trait of Blanchotian ontology. It pulls and pulls over the thinking subject to the incommensurable by insisting on the constitutive (even though regulative in Kantian terminology!) relatedness of the subject to that which by definition is unavailable to it. That is the meaning of the dictum about metaphysics as a natural capacity, this originary self-transgression and self-surpassing of the finite subject to the dimension of the infinite which Blanchot calls the exterior (dehors) and Deleuze & Guattari, following Nietzsche, call becoming, chaos or the untimely.