DIE FREUNDSCHAFT VON KUNST UND PHILOSOPHIE LECTURE ZUM LAUNCH DER ZEITSCHRIFT "INAESTHETIK". KUNSTHALLE ZÜRICH, 14.06.08

Tobias Huber (Hg.), Marcus Steinweg (Hg.)

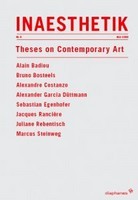

INAESTHETIK – NR. 0

Theses on Contemporary Art

INAESTHETIK – NR. 0

Theses on Contemporary Art

--------

INÄSTHETIK – NR. 0

Theses on Contemporary Art

Editorial Nr. 0

›Inaesthetics‹ is a concept introduced by Alain Badiou. It designates the relationship between art and philosophy. In his Petit Manuel d’inesthétique from 1998, Badiou defined this relationship more closely. Badiou distinguishes three schemata by which this relationship has been defined through the course of its history: the didactic schema, the Romantic schema and the classical schema: »In didacticism, philosophy is tied to art in the modality of an educational surveillance of art’s purpose, which views it as extrinsic to truth. In romanticism, art realizes within finitude all the subjective education of which the philosophical infinity of the idea is capable. In classicism, art captures desire and shapes its transference by proposing a semblance of its object.« Obviously it is high time to think through a relationship between art and philosophy in which art no longer functions as an »object for philosophy«.

»By ›inaesthetics‹ I understand a relation of philosophy to art that, maintaining that art is itself a producer of truths, makes no claim to turn art into an object for philosophy. Against aesthetic speculation, inaesthetics describes the strictly intraphilosophical effects produced by the independent existence of some works of art.«

The linking of art and philosophy should not take place at the price of reducing philosophy to art. Neither should philosophy surrender itself to a Romantic transfiguration of the art work in order finally to want to become art itself (on this line Badiou positions Heidegger, among others), nor is art an illustration of conceptual thinking. Art and philosophy are linked by a certain relation to truth. Art produces truths and it is the task of philosophy »to showing it as it is«, to function as a kind of »go-between in our encounters with truths«.

The idea for the journal, INAESTHETICS, lies here, in insisting on an alliance or friendship between two independent ways of touching truth. Art and philosophy belong together insofar as each maintains its autonomy. Just as there can only be friendship between autonomous subjects, no matter how jeopardized and vulnerable this autonomy may be, the friendship between art and philosophy can only be thought as an alliance between autonomous contacts with truth. The journal, INAESTHETICS, is dedicated above all to this idea or, let us say, as ingenuously as possible to this ideal of autonomous collaboration and friendship. Our aim is, instead of pursuing a single direction in thinking, to give room to the contradictoriness which keeps the thinking of art and the thinking of philosophy, as well as the thinking of the friendship between art and philosophy, in a state of permanent restlessness, a restlessness stemming from contacts with truth itself insofar as by truth we understand that which prevents the subject from calming itself down and enclosing itself in its everyday evidence. Perhaps art and philosophy are privileged ways of shaking up evidence since their assertions of form and truth do not seem to be made to confirm the subject in its opinions and certainties. The experience of art and philosophy always leads the subject of these experiences into an area of uncertainty and unsureness. At the limit of the established realities of facts, the subject begins to experience its realities as inconsistencies, as, at least, porous constants whose constancy remains doubtful. Deleuze was probably right in expecting of art and philosophy that they measure their consistencies against the abyss of that inconsistency which he calls chaos.

If art has something to do with truth, then in the following sense: instead of revealing truths like facts, the art work is the locus of the separation of truth and facts insofar as facts, in the light of their uncovering, blot out the chaotic non-ground which itself does not appear in the light of facts and, by definition, cannot appear in this light. To touch a truth means to make contact with this non-ground which, citing Hegel, Cornelius Castoriadis (as well as, incidentally, Slavoj Žižek) connotes with the »night of the world«. In a well-known passage from the Jena Realphilosophie, Hegel sketches this ghostly scenario concerning the subject qua subject: »The human being is this night, this empty nothingness which contains everything in its simplicity, a wealth of infinitely many ideas, images, of which none simply occurs to it or which are not present. This [is] the night, the interior of nature which exists here — pure self. In phantasmagoric ideas, all around it is night; here a bloody head then suddenly shoots forth, there another white shape, both disappearing just as suddenly. We see this night when we look a human being in the eye, into a night which becomes terrible; the night of the world dangles here before us.«

The night of the world is another name for the chaos which the subject’s subjectivity is. The subject’s self-confrontation demands of it to open itself up to this zone which is as full of riches as it is empty. It is the realm of something real which has not yet assumed the form of reality, the dimension of an abyss which marks the »infinite possibility of representation«, its impossibility. The art work, as well as the subject, is related to this abyss, to this instability or blurredness which makes its stabilization within the established pattern of reality difficult. Truth is a name for this instability which tears the art work, as well as the subject, beyond itself into the night of indefiniteness. Therefore, instead of comprehensibility, clarity is an attribute of art, because clarity evokes the limit of what is comprehensible. The art work’s transparency opens it up to an intransparency which belongs to it not merely subsequently, but originally.

In this sense, art is an assertion of form by measuring a form to the opening onto formlessness which relates the subject of this problematic measuring to the immeasurable. One must gather the courage to connect the always headless assertion which the art work is with the clarity of a decision which is itself unsecured and which withdraws from the dictatorship of comprehensibility and communication. The assertion of the work is not headless because it is simply subjective or arbitrary. Although any assertion comes from the indefinite subjectivity of the artistic subject, just as much does it refuse the expressive gesture of the ego and the metaphysics of interiority associated with it (Badiou has said what is necessary to say about this) — the assertion refuses to narcissistically make itself into an enigma like bad art does.

One attribute of the art work is that it does not hide anything, and does not have anything to hide because it has long since been adjacent to opacity and intransparency. As a »window on chaos« and »presentation of the abyss«, art is »not phenomenal«, but »transparent«. »In it, there is never anything hidden behind something else.« Castoriadis is right to free art (which he calls »great art«) from the temptation of a subjective self-weakening, from the power of diffuseness as well as from the appeals of the Zeitgeist which reduce it to a documentary reflex, to critical reflection. The work’s transparency includes a transcendence to an intransparency beyond critical reflection. The art work embodies this twofold resistance: it neither bends to the obscurantism of critical evidence (in order ultimately to assimilate itself into journalism), nor does it ally itself with a diffuse obscurantism or any kind of metaphysics of the artist.

In this pilot issue of INAESTHETICS, we are glad to be able to collect, besides Badiou’s fifteen theses, articles which mostly, implicitly or explicitly, have opened themselves to Badiouian thinking in order to think this thinking further, that is, in order to carry it beyond itself in a movement of autonomy which demands of thinking that it do something other than merely think about the thinking of other thinkers instead of thinking for itself, that is, instead of philosophizing. We want to establish INAESTHETICS as a place of encounter between art and philosophy. And, as we all know, an encounter can only take place when its outcome and consequences remain uncertain.

Tobias Huber & Marcus Steinweg

Zurich-Berlin, April 2008

Translation: Michael Eldred

Editorial

Alain Badiou: Thèses sur l’art contemporain / Fifteen theses on contemporary art / 15 Thesen zur zeitgenössischen Kunst

Bruno Bosteels im Gespräch mit Alain Badiou: Kann man das Neue denken?

Bruno Bosteels: Art, Politics, History: Notes on Badiou and Rancière / Kunst, Politik, Geschichte: Bemerkungen zu Badiou und Rancière

Alexandre Costanzo: L’Odyssée du réel / Odyssee des Realen

Jacques Rancière: Penser entre les disciplines: une esthétique de la connaissance / Zwischen den Disziplinen denken: eine Ästhetik des Wissens

Zur Aktualität ästhetischer Autonomie: Juliane Rebentisch im Gespräch

Marcus Steinweg: Definition der Kunst / Definition of Art

Sebastian Egenhofer: Zur Topik des Werkbegriffs in der Moderne

Alexander García Düttmann: Der Schein