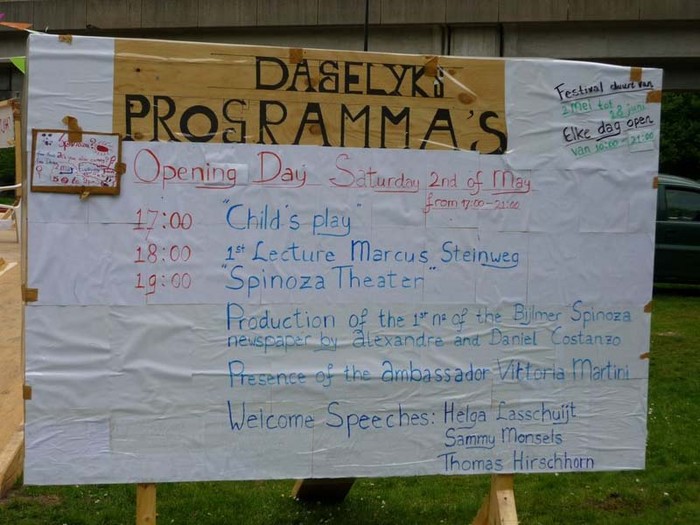

WHAT IS PHILOSOPHY? 1ST LECTURE AT THE BIJLMER SPINOZA-FESTIVAL BY MARCUS STEINWEG (ABSTRACT)

THE BIJLMER SPINOZA-FESTIVAL

AN ARTWORK BY THOMAS HIRSCHHORN

http://www.thebijlmerspinozafestival.nl/_home/home.html

AN ARTWORK BY THOMAS HIRSCHHORN

http://www.thebijlmerspinozafestival.nl/_home/home.html

What is philosophy? Philosophy is the courage not to evade the call of great concepts: What is the human being? What is justice? What is truth? What is freedom? What is love? These, and other, oversized questions and concepts are the questions and concepts of philosophy. In philosophy it is always a matter of seeking out these hyperbolic categories. We know that philosophy of the twentieth century (which on the whole is critical of philosophy and metaphysics, metaphysics being another name for philosophy which has opened itself to the great concepts, starting with Nietzsche, from this turntable Nietzsche, as Habermas says 2) articulates itself in a way critical of philosophy in the sense that it accuses philosophy of recurring to idealist entities with these oversized concepts whose sense and existence has to be doubted. The philosophy of the twentieth century established a kind of mistrustful thinking. What Wittgenstein, Heidegger, the Frankfurt School, structuralist and post-structuralist thinking share beyond their excessive difference is thus a hyperbolic mistrust of these hyperbolic concepts that begins to doubt the sense in addressing them. Against this universal mistrust I insist on reactivating these oversized concepts as appellative addresses of philosophical practice, to define philosophy as the reactivation of this relationship, of this opening toward these hyperbolic categories. My assertion is that the mode of being of these concepts which philosophy tries to touch is their specific non-existence. These concepts cannot be filled. Therefore, philosophy is humiliated by sound common sense because common sense always has right on its side, just as doxa always has right on its side as long as it accuses philosophy of dealing with non-existents, and therefore of being in the wrong. Thus, instead of resisting the accusation of factual illegitimacy, philosophy should affirm itself as an opening toward non-existence, for that is what makes it into such a breathless and necessarily blind practice: that it moves within the space of total illegitimacy.

The subject of philosophy shares with the subject of art the courage to accelerate itself toward these empty entities which mark nothing other than their non-existence within the universe of established realities. Here I see a connection between art and philosophy: art and philosophy share a not-being-in-agreement with reality as it exists as instituted reality, as a complex, self-contradictory system. Despite this complexity and heterodoxy it makes sense to unify this concept of reality, even though it remains a strategic unification. The concept of reality I propose (completely in the sense of that which is usually called reality, insofar as this homogenization is tenable) marks this consistent universe of shared familiarities, this zone of evidence in which communication is possible, in which we make ourselves understood without having to constantly additionally clarify the concepts we use, and which as this realm of familiarities is the space of functioning. We could not live at all if we had to constantly put into question the consistency and reliability of the concepts of which we make use in this zone. The philosophical subject, philosophical practice as this breathless self-acceleration, includes this massive resistance against the universe of consistencies or realities. This is where I see the friendship between art and philosophy: in the shared refusal to allow oneself to be neutralized in the space of facts of shared evidence by articulating an almost blind resistance.