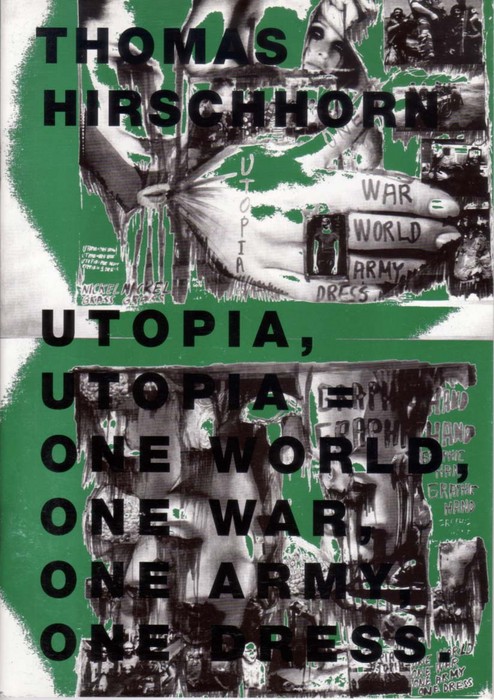

WORLDPLAY INTEGRATED TEXT FOR: THOMAS HIRSCHHORN, "UTOPIA, UTOPIA = ONE WORLD, ONE WAR, ONE ARMY, ONE DRESS,"

I will write 20 integrated texts for “UTOPIA UTOPIA”. I want to write about the WORLD. About the world as a philosophical concept. About the WORLD-IMMANENCE. About the one world divided in a multiplicity of SUB-WORLDS.

It will write about the necessity of reinventing itself in relation to the world as a whole. There is no exterior to this one world. There is no transcendence at all. We have to think and to act within the one world, here and now.

The subject of FREEDOM is BEING-IN-THE-WORLD. The world does not stand over against it like an object. It finds itself originarily in the world. It has always already transcended itself toward world.

That means: the responsibility for the world makes part of the ontological structure of this subject. The question is: how to remain free in the space of objective unfreedom, that is the REALITY or the WORLD. How is FREEDOM possible for a SUBJECT that refuses both: to flee the one WORLD-SPACE in dreams or phantasms (of “better worlds”) and to reduce itself on the established WORLD-STRUCTURE?

MARCUS STEINWEG

It will write about the necessity of reinventing itself in relation to the world as a whole. There is no exterior to this one world. There is no transcendence at all. We have to think and to act within the one world, here and now.

The subject of FREEDOM is BEING-IN-THE-WORLD. The world does not stand over against it like an object. It finds itself originarily in the world. It has always already transcended itself toward world.

That means: the responsibility for the world makes part of the ontological structure of this subject. The question is: how to remain free in the space of objective unfreedom, that is the REALITY or the WORLD. How is FREEDOM possible for a SUBJECT that refuses both: to flee the one WORLD-SPACE in dreams or phantasms (of “better worlds”) and to reduce itself on the established WORLD-STRUCTURE?

MARCUS STEINWEG

INTEGRATED TEXT for:

Thomas Hirschhorn, "Utopia, Utopia = One World, One War, One Army, One Dress," installation view, 2005.

Courtesy of the artist and Barbara Gladstone Gallery, New York. Photo: John Kennard.

Thomas Hirschhorn, "Utopia, Utopia = One World, One War, One Army, One Dress," installation view, 2005.

Courtesy of the artist and Barbara Gladstone Gallery, New York. Photo: John Kennard.

"We Hyperboreans" is how Nietzsche headed a fragment from his unpublished works dated November 1887. A few months later he wrote The Anti-Christ.

We Hyperboreans, we who live in the "hyperborean zone", in inhospitability or uninhabitability itself, the exterior. The "hyperborean zone that is far removed from the temperate zones". We Hyperboreans, we immoderates who only exist in contact with the immeasurable, the unmeasurable or incommensurable, we who would rather live "in the ice", says Nietzsche, we withdraw from the "fake peace" and the "cowardly compromise" of a certain "tolerance" and "largesse of the heart". We resist the "happiness of weaklings" and the ethics of compassion which these "weak ones" demand (for themselves, for good reasons) rather than practising it themselves. And soon after Nietzsche pronounces one of his most monstrous statements ("The weak and the failed shall go under: first maxim of our love of humanity"), we read, "Nothing is more unhealthy in the midst of our unhealthy modernity than Christian compassion. To be a physician here, to be merciless here, to wield the knife here — that is part of us, that is our love of humanity, with this we are philosophers, we Hyperboreans!"

Hyperboreanism seems to be connected with a certain we, with the we of the philosophers. As if the position of this elementary singularity, the thinking of the essential solitude of the hyperborean subject could only be articulated through a kind of paradox or contradiction. As if one had to be in company to legitimize one's solitude.

We Hyperboreans also means: we, the community of those who are without community, without we-community. We solitary ones. We singularities. We who touch the limits of the Logos that represents the principle of the Western we-community. We who have fallen out of the we-cosmos. We who have separated from the universality of a transcendental community, from the habitable zone of transcendental we-subjectivity. We homeless ones. We arctic natures. We monsters who are in contact with the limits of what is familiar, habitual and habitable. We contact-subjects, we border-natures, we come up against this limit and accelerate beyond this limit. We uncanny ones or, as Heidegger also says, we homeless ones. We who are at home in being homeless in uncanny homelessness. We over-confident ones, we exaggerated ones. We are subjects of an always violent self-overcoming. Subjects of self-overwinding, of self-over-stimulation and self-unbounding. We who are who we are by betraying the idea of the we and our self through transgression. We traitors, we non-identical ones without a secured origin or future, we faceless ones, we should confront ourselves with ourselves by learning to look ourselves in the face.

"Let us look ourselves in the face," the first lines of The Anti-Christ demand, "we are Hyperboreans, — we know well enough how far removed we live. 'Neither by land, nor by sea will you find the way to the Hyperboreans', that is what Pindar already knew about us. Beyond the North, the ice, beyond death — our life, our happiness ... we have discovered happiness, we know the way, we found the way out of all the millennia of the labyrinth."

The hyperborean subject is the hyperbolic subject of self-transgression and self-surpassing toward an absolute exterior that is Uninhabitability itself, Chaos, Incommensurability as such. It is the subject of a non-identity-building self-assertion, subject of failed anamnesis, of transcendental non-recognizability, subject without name, without memory, without teleological inscription, subject of transcendental facelessness — barbaric subject.

Barbarians touch chaos. The barbarian has the aggressiveness and uncompromisingness of the inventor ahead of his time who denies what lies in the past and what is only present, in order to enable something new for which the reason of the times, sound common-sense and moral considerations (mostly they are indistinguishable) are lacking an eye, imagination, language, courage and decisiveness. "Among the great creators there have always been the relentless ones who to start with made a clean slate." To start again from the beginning, the barbarians have to leave behind what is old. They have to hazard a kind of risky forgetfulness, active and self-assured amnesia. "Just as the one who acts, according to Goethe's expression, is always without a conscience, he is also without knowledge; he forgets almost everything to do one thing; he is unjust against what lies behind him and knows only one right, the right of that which now should become."

Barbarians try to rejuvenate humankind. They want to renew it in the spirit of an uncertain future. The "new task" of the "new barbarians" is "to create a new locus in a non-locus, to construct ontologically new determinations of human being, of life — a powerful artificiality of being". Like Benjamin's destructive character, they must themselves be "young and cheerful". The cheerfulness liberates the barbarian from the burden of the past. It gives him the lightness of birds. Barbarians can only be cheerful and confident like aeronauts. They throw themselves toward the sun like Icarus who, acting crazy at the moment of flight, already on high, suddenly flies higher, increasing the hubris by starting to soar even higher.

The barbarian does not seek the protection of the clouds. He denies himself this protection. Instead of staying on the ground administering his treasures, he rushes away from the earth. He cuts himself off from it, to pass through a space that lies beyond his possibilities and beyond what is reasonable. The barbarian has to leave the universe of reason in order to go through unheard-of, unbearable and improbable experiences. He must make contact with chaos.

Chaos is the lack of ground or the abyss. It is the dimension which forever precedes the Logos, reason, language and communication. The Logos refers to this abyss. It points to it. The abyss of the Logos cannot be thought as ground. The Logos glides over its own groundlessness. From the outset it is held above the space of absolute secrecy. The Logos constitutes itself as a primary speaking. It is the name of the birth of sense from non-sense. A subject is what keeps contact with non-sense through the Logos and the madness inherent in it without losing itself in this contact to the pure power of chaos. The peculiarity of the subject’s contact with the chaotic abyss, which always also means re-contact, resumption of an original or, more precisely, pre-original intimacy, lies in this hyperbolic self-transgression and self-surpassing in which the subject constitutes itself as the subject of this transgressedness, of a certain self-transcendence. The human being as subject, says Zizek citing Schelling, "is the only creature that is (again) directly in contact with the primal abyss".

2. The hypochondriac world

The hyperborean subject inhabits the universe of facts without assimilating itself, like the hypochondriac subject, to the order of facts. The world of facts is the world of objective unfreedom, the world of determinants, laws, definitions. It is the world that has already been decided, the universe of recognized, official and instituted factual truths — reality. The hyperborean subject is the subject of a certain denial of reality. It withdraws from the imperatives of the idealism of facts in order to open itself to another world, another order than (established) reality. The Hyperboreans inhabit the borders of reality, the edge of the earth in order to make contact with the real of reality, its impossibility and inherent incommensurability, chaos itself. They are contact subjects of this touching of the untouchable, the absolute limit of any conceivable reality.

Touching the untouchable, the incommensurability of the real or the exterior demands of the subject of touch a certain degree of strength and courage of will. The subject of touch is the subject of freedom to self-alienation, self-transgression and self-surpassing. Instead of enclosing itself in its self-image, it must find the courage to activate another self. It is the subject of a necessarily auto-aggressive self-elevation through which it transfers all responsibility to itself, "infinite responsibility," which contraposes itself infinitely "to every kind of good conscience". Wanting and willing to take on responsibility means not delegating the authority to make decisions to others. Through the subject exposing itself to the experience of freedom unreservedly and undiminished, it wants to be responsible for itself in view of itself and the selfhood of other subjects. "For what is freedom? That one has the will to self-responsibility." It exposes itself to its self and the selves of other subjects. It resists and contradicts at the moment of this experience of "morality of dissolution of the self" which Nietzsche calls "the morality of decline par excellence". The morality of dissolution of the self is a morality of self-circumcision, of auto-castration and willed weakness which articulate its power as a counter-power to life and its possibilities. To be strong means to be active. It means to will, to cultivate the activity of willing, to will a self. "The active, successful natures do not act according to the maxim 'know thyself', but as if they imagined the command: will a self and you will become a self. Destiny seems to have still left them the choice, whereas the inactive and contemplative ones reflect upon how they have chosen once, that one time when entering life."

The domain of the hypochondriac, its world, is the zone of suffering, of loss and defectiveness. "The hypochondriac is a person who has retained just enough spirit and pleasure in spirit to regard its suffering, its loss, its defects thoroughly, but its domain on which its nourishes itself is too small. It grazes on it until finally it has to scrounge for single blades of grass. In the end it becomes envious and miserly, and then it is unbearable." The hypochondriac world is the always too small world of resentment and self-denial. Self-denial is a flight from responsibility, suffering under one's self, under the freedom to decide and the possibility of responsible subjectivity. Self-denial flees from the cruelty associated with the freedom to responsibility. Ultimately one will have to recognize what itself represents a cruelty, that the principle of responsibility cannot be clearly distinguished from the principle of cruelty. To be hypochondriac means to enclose oneself and secure oneself in one's passivity and 'weakness'. It means to renounce the possibility to be a self, and it often means to be 'strong' and 'authoritarian' in a weak, resentful and revengeful sense. Deleuze writes, "These 'weaklings', these people full of resentment who wait for their revenge, especially enjoy a hardness which they have turned to their own advantage, to their own fame, but which comes from somewhere else". Nietzsche can therefore say that the subject has to protect itself against the weak, that it has to arm itself against them. The hypochondriacs are not the miserable ones; they are not the ones who have been mistreated, humiliated and humbled by the 'rulers' or the 'powerful', the situation or the circumstances. Hypochondriacs are those who want to be weak. Their activity is restricted to this will to weakness. The will to weakness is the will to non-will, to passivity and an essential will-lessness. The will-lessness guarantees the weak that they are unfree and irresponsible. The weak affirm themselves in their weakness. They celebrate their weakness like a secret triumph. The weakness seems to make them immune against the demand to be responsible for themselves and others. The weak privilege unfreedom — their unfreedom, weakness and irresponsibility — in order not to have to be strong, in order to be the object of circumstances, of history, of the decisions of others. The weak criticize the strong as those who are authoritarian and hungry for power. The weak reject the strong as their oppressors. They conceal the knowledge or the inkling that they are also their liberators in the perverse sense in which it can be comfortable to be 'oppressed' and freed from self-responsibility. The complacency of the 'oppressed' lies in the fact that as 'victim' they do not bear any responsibility for complicity with their status as object. They cannot be anything other than victim. They therefore have pity for themselves as victims. The weak and oppressed fear no longer being victims. They defend their status as victims like a rare privilege. The weak pretend to fight against their weakness, but what they really fight against are the paths of freedom that lead out of alien objectivation.

3. New world

The new world is the world of the new human being. The new human being is the human of self-overcoming, the Hyperborean human. Nietzsche thinks self-overcoming as a "stage of overcoming the human being". The self-overcoming human is the subject of a necessarily auto-aggressive self-transcendence. The transcendence refers to the subjectivity, the non-substantial being of the subject. There is something resembling a subject only as the subject of a constant self-transgression and self-surpassing. The subject crosses itself out as subject. The subject is what affirms itself as the locus of this crossing-out, of this becoming, the restlessness of a subject without subjectivity. "If one chooses for the being that we are ourselves the term 'subject'," says Heidegger, "then it holds that transcendence designates the essence of the subject, that it is the basic structure of subjectivity. The subject never exists previously as a 'subject' in order then, in case there are no objects present, also to transcend, but rather to be a subject means to be a being in and as transcendence".

Transcendence is the essence of a subject without essence. The subject is the ecstatic subject of a primordial self-transgression and self-surpassing. It is the subject of this ontological nakedness and poverty, to be nothing but a subject of emptiness, indeterminacy and lack of essence. This subject appears in the thinking of the twentieth century as the subject of homelessness (Heidegger), as the subject of the exterior (Blanchot), as the subject of freedom, i.e. of nothingness (Sartre), as the subject of ontological lack (Lacan), as the subject of chaos (Deleuze/Guattari), as the subject of de-subjectivation and self-care (Foucault), as the subject of the other (Levinas), as the subject of différance (Derrida) and as the subject of the event of truth (Badiou). It is a subject whose subjectivity seems to equate with the dimension of the non-subjective, of nothingness, a subject without subjectivity. To be a subject means to have transgressed oneself toward an exterior, an otherness and impossibility in order to affirm oneself as the subject of transgression. The new subject is neither a subject of faith nor a subject of knowledge; it is neither creature nor cogito nor self-consciousness. It is a super-subject or Uebermensch, subject of freedom contraposed to the categories of the last and higher human. The higher human is not yet the Uebermensch. Instead of enslaving itself to God, the higher human enslaves itself to itself. It assumes a duty toward itself. The higher human is the human of knowledge, of duty and humanity. It "takes a burden upon itself," as Deleuze says, it "harnesses itself on its own, and that in the name of heroic values, in the name of values of the human being". The Uebermensch, by contrast, is the free human being, a Dionysian subject. It is not the human being of human and all-too-human values. It represents the surpassing of the simple surpassing, the transgressing of the simple transgressing of God by the higher human. The Uebermensch surpasses both the higher and the last human. It affirms a new, super-human, transhistorical human being; it affirms itself as an invention which is without parallel in history.

Zarathustra announces this human of the here and now, of haecceitas, of hæcceity in speaking of the Uebermensch. The Uebermensch is the human of affirmation. It affirms the eternal recurrence of the same by affirming the past as necessity, the present and future as opening, possibility and opportunity. The eternal recurrence does not mean that everything has already been done and decided. It does not correspond to any doctrine of recurrence of the past. The eternal recurrence does not have any other meaning than to introduce an absolute restlessness. It opens the subject to the future and to the unknown. The eternal recurrence means that everything still needs to be done, that everything is still undecided. It is the principle of activity and of will, the principle of "affirmation of becoming and acting". The eternal recurrence tears the subject into the turbulence of a freedom that tears it apart. It brings movement, acceleration into the subject. To affirm the eternal recurrence means with the death of God to affirm the birth of a new human being, a new mobility, a new cheerfulness, an other justice and politics.

The new human being of the new world is the Uebermensch. It is the human being beyond the last and beyond the higher human, the human of affirmation and unbridled, non-negative cheerfulness, the human of innocence, the child-human. The Uebermensch is Zarathustra's child, his prophet. "Zarathustra calls the Uebermensch his child, but he is surpassed by his child, whose true father is Dionysos." Zarathustra is a transition, he is a mediator. After him comes the human being beyond the (previous) human. This is the Uebermensch. It is the human being without a beyond, the human being of the here and now, of hæcceity, of immanence. This human being is cheerful and playful in the midst of the cruelty of beings, in the midst of the "tender indifference of the world". It is the human being of a new extra-moral responsibility and a justice beyond established law. The Uebermensch is Nietzsche's invention; it is Zarathustra's and Dionysos' child, and it is itself an inventor. It invents a new responsibility. In the midst of the cruelty of beings, in view of the law of eternal recurrence, the new human being is to be responsible for itself. The eternal recurrence liberates the human to action and activity. "No longer to will and no longer to value and no longer to create — oh pray that this great tiredness always remain far removed from me," says Zarathustra.

To will, value, create are the modes of existence of the new, responsible and free human being. Nevertheless, Nietzsche, as well as Deleuze, seems to evade the final consequence that follows from the thought of the Uebermensch and of singularity. Nietzsche has to distinguish the Uebermensch from the higher human, the subject of facts, by an innocence which only gains sense via the epoché or arresting of the category of truth, as if truth were nothing other than the truth of knowledge, as if truth designated nothing other than a naïvety and a belief, the credulity of the realist, of the "last idealist of knowledge," as he puts it. "These are still far from being free spirits because they still believe in truth..." And what would happen if we tried to distinguish between a belief in truth and a love of truth? The subject of the belief in truth is a hypochondriac subject of self-securing in the necessarily idealist principle of knowledge-truth, whereas the subject of the love of truth constitutes itself as a hyperborean subject touching truth, that is, contacting non-sense, the exterior, chaos and nothingness. The subject of the love of truth is the subject of self-transcendence to the dimension of truth which cannot be reduced to the sphere of knowing, or that of not-knowing or of faith. Truth is not the truth of knowledge, of faith or of facts. Truth marks the border between systems of knowledge, faith and facts, in Lacanian terminology, the real of reality. The subject of self-transcendence is the subject of the real. It is the subject of truth, of a truth which belongs to the world of facts as its immanent limitation without being reducible to this world.

What distinguishes the love of truth from the belief in truth is that the subject of this love does not presuppose truth as given substantially. Only in touching truth does truth constitute itself. Truth means nothing other than the untouchable, the beyond of the possible, its limit. To touch a truth, the untouchable means to step outside of what is knowable. It means to lose all belief in one's 'identity', one's socio-historical being, in oneself as a person, as a subject.

4. World of facts

"To be a philosopher, to be a mummy," writes Nietzsche in Twilight of the Idols. The philosophers — ancient and present-day philosophers, which he distinguishes from the future or coming or new philosophers — operate with "conceptual mummies", they "kill, they stuff"..Their morality lies in the flight from becoming, from diversity, from the sensuous, from history, from change, from life, which eludes being incarcerated in concepts and systems. It is a morality of flight. It flees what represents an overtaxation of it: what is non-representable, nameless, incommensurable. This is what makes these philosophers weak so that they do not have the courage to squander themselves by touching the untouchable, so that they prefer to measure out the space of possibility rather than making contact with the impossible. "What constitutes the style of philosophy is that in it the relation to an exterior is always mediated and weakened by an interior, within an interior. In contrast to this, Nietzsche founds thinking and writing on a direct relation with the exterior." The coming philosophers are philosophers who give up the metaphysics of interiority in favour of touching chaos, i.e. truth, in order "to risk contact with a pure exterior". The subject of this contact is the subject of self-transgression and self-surpassing into the dimension of an otherness that undermines a priori every concept of self and identity. It is a subject without any fixed identity, a subject that constitutes itself in the act of (re-)contacting its own essential abyss as ontological deviation, as originary disturbance of the world of facts, of the positive order of being.

The world of facts is another name for reality. The reality of facts is the world of official, established, recognized, institutionalized and archived factual truths. It is the universe of present-day and historical knowledge, of opinions, of inclinations and interests. The world of facts is a sphere which by definition excludes truth in order to enable social, political, cultural, that is, identifiable reality. Realities or factual truths are truths that are not truths. The space of facts is constituted through the pathological exclusion of truths because truth is the name for precisely that experience which prevents identity. To privilege facts over possible truths means to prefer a model of identity to the horror of the experience of non-identity, of incommensurability, of pre-ontological chaos. The subject of facts is an identity-subject that holds on to its self. It is a dead subject if one understands death as the "mode of existence of the last human". The last human is the human of the exclusion of truth, sense and life, and the human of small facts, "petit faits", the 'faitallistic' human. "Wanting to stand still before the facts, the factum brutum," is what Nietzsche calls in The Genealogy of Morals the "fatalism of 'petit faits'", "petit faitalism". The human of facts reduces itself to the facts. It makes its dead truth from the facts. It is the subject of belief in facts, of the fatalism of facts and the obscurantism of facts. The facts, the realities are its unshakeable law.

The realism of facts of the subjects of facts corresponds to the will to self-reduction of this subject to its factual or object status. The subject of facts does not want to be a subject (of truth). The world of facts is the space of doxa, of interests and illusions which hinder or prevent contact with the truth of the subject. It is the sphere of untruth. A factual truth can have no other sense than to prevent truth. The subject of factual truth is therefore the subject of cynicism, of depression, of narcissism and its self-accusing lachrymosity. Facts are untruths invented to prevent truths. Subjects who do not want to be subjects refer to the facts. The subjects of facts are subjects of a continual self-desubjectivation. The subject of facts refers to itself as if to a thing, an object, an unchangeable fact. It is the subject of a self-willed impotence, subject of Angst. It flees from the necessity to touch the truth of factual truths, i.e. the real of reality.

The real is the name for that which does not belong to the space of facts. The real names the border and the constitutive exterior of the factual dimension. The real is more real than reality. It is what inscribes a fundamental inconsistency into 'realistic' calculation, the idealism of facts. To touch the real is to touch this inconsistency, this weak link in the system of facts.

5. The real world

The world of facts is the world of community, a shared reality. The subject shares the space of untruth, the reality of certainties with other subjects. It articulates itself in this space as the we-subjects of its interests, its opinions and fantasies. It is the subject of intersubjective communication, community subject in the socio-cultural symbolic space. The real world has to be distinguished from the we-reality, the sphere of certitudo. It is the world of interrupted relationships, failed communication, the world of silence, of chaos, the exterior, uncanniness — lonely world in which the subject without subjectivity wanders aimlessly, hyperborean "world of isolation, singularity, not belonging".

The subject cannot settle in the real, in truth. It is the subject of an unshared restlessness, hyperbolic acceleration, atomic nervousness, subject of essential or hyperborean solitude. The real world is the uninhabitable world, the world of truth which the subject traverses without belonging to it. The real names the pure abyss of its subjectivity. This is the pre-ontological nothingness to which the subject remains related as its abyssal ground, the non-ground of its ontological indeterminacy and irreducible lack of focus, the hole of freedom, as Sartre says. The subject of the real is the subject of this fathomlessness and indeterminacy. It is the subject of ontological poverty, subject without an identity-constituting, transcendent or teleological regulative.

Who would be surprised that Nietzsche opened up his subject to a possible future, an impossible or real we, a we that does not exist? The space of this we, the order of we-singularities, of philosophers of the future, of free spirits, first has to be constituted in touching this space. The universe of inter-singularity does not exist as such. It is an invoked space that is only opened up in the invocation, a zone of impossibility in which singularity meets singularity, Hyperborean meets Hyperborean. Singularities are subjects in the real, subjects that have fallen out of reality or evaded it from the outset, that inhabit its impossibility as the condition of possibility of their freedom and responsibility. They inhabit the uninhabitable space, truth as the zone of solitude to whose denial or forcing-back the symbolic universe owes its existence.

Real subjects will be subjects of a truth other than the truth of certainty. This other truth is another name for the immanent limitation of the sphere of certainty. Truth is what is contraposed at any point in time to certainty and to any form of knowledge and non-knowledge in the name of another enlightenment, as Nietzsche so often says, of another philosophy or another thinking that thinks otherwise. The subject of certainty is the subject of the reality of facts. Certainty is necessarily the certainty of facts. Truth is what interrupts the possibility of certainty, that is, of reassuring oneself in the universe of facts by believing in facts. The subjects of this interruption are "incommensurable subjects" of incommensurability, "subjects without subject and without inter-subjectivity", solitary hyperborean singularities of uncertainty whose truth is associated with making shared truth, that is, the certainty of the subject, impossible, subject-singularities without subjectivity.

6. Dream world

To distinguish the world of facts, of the possible, from the world of the real, the impossible — is this possible without opening up to the impossible, to that which Adorno and Derrida call the possibility of the impossible?

The subject of this opening would open up to an irreducible closure, an originary forgetting, to primordial Lethe, without injuring it, without doing violence to the impossible. As in sleep, with the proverbial sureness of a neither merely sleeping nor merely waking somnambulist, this subject would balance between the possible and the impossible, opening and closure, reality and the real, between consciousness and the unconscious, between knowing and not knowing. "The possibility of the impossible can only be dreamt; it can only exist as something dreamt."

Although they are nothing less than unambiguous and decidable, these oppositions are nevertheless known. The real is to be distinguished from the non-real, essence from appearance, truth from fiction. At the beginning of Western thinking, Heraclitus related them to the difference between waking consciousness and dreaming consciousness, day and night, "For those who are awake there is one, common world, but in falling asleep each turns away to its own".

The subject of sleep has transgressed itself into the night of non-evidence, into the darkness of the impossible. It flies over the space of mere facts and their transcendental, historical determinants. Sleeping, dreaming, flying, it accelerates toward the unknown, the incalculable, the incommensurable. In this turning toward, it turns away from the domain of daily certainties, from the objective sphere which holds it in the known. Flying implies all the risks of lifting off, of speed and crashing. Flying demands the courage to an unknown movement into the unknown. Flying is the form of movement of philosophy, of another philosophy withdrawn from evidence, from light and enlightenment, from the imperatives of facts, from the dictatorship of the light of facts, to hold itself in readiness for the dream of a new enlightenment dreamt by Nietzsche, for the dream of a new enlightenment emancipated from the obscurantism of facts which unleashes the dreams of a new, coming philosophy, a new reason, a new responsibility and thus another world of light. Like every dream, the dream of this other light, the dream of truth, is the event of a liberation and unleashing which can no longer close itself off to the truth of the dream. It is as if it were a matter of remaining watchful for this double truth, for the dream of truth and for the truth of dream beyond the ruling certainties and the norm of truth represented by them. The world of facts is the common world of shared evidences, whereas in sleep, the subject opens up to more lonely worlds populated by it alone which are the worlds of its dreams, the universe of the impossible. "It is as if the dream were more wakeful than waking and the unconscious more conscious than consciousness." It is as if it were a matter of at first and above all accepting responsibility for one's own dreams and one's own unconscious. "In everything you want to be responsible," says an aphorism from Red Dawning, "Not only for your dreams! What miserable weakness, what a lack of consistent courage! Nothing is more your own than your dreams! Nothing is more your work!"

That which is the human's ownmost does not belong to the human. This is perhaps also the most radical aspect of Heidegger's thinking: whilst simultaneously insisting on the necessity of the question concerning the ownmost, to have thought this ownmost as that which is absolutely alien. Human being 'is', like being itself, that which surpasses and transgresses human being, Dasein. This is the meaning of the so-called ontological difference between being and beings, that the being called human being inhabits its being like something absolutely alien, like an endless dream. For this dream-subject, going through the experience of the self means at the same time to go through the experience of the alien, the experience of what overtaxes its self. The subject of this experience has to surpass and transgress itself in order to be with itself. It is, to be precise, only at the moment of its transgression and surpassing in becoming other than it is.

7. Dream ethics

Let us not turn Antigone into a prophet. Let us renounce this dream in order not to dream every night of her desire, like one dreams of something toward which the most naked of expectations is directed. Because here, as always, it is a matter of the question of responsibility as a response to the question whether there is a responsibility to dream beyond the dream and beyond the dreamy preparedness for happiness. "Is one responsible for one's own dreams? Can one accept responsibility for them?" asks Derrida. Perhaps there is responsibility only in the form of this question insofar as it is already a response to a question that has not been posed and that cannot be posed. Perhaps it is a necessary part of responsibility as this questioning response to an impossible question that it remain alien and questionable to itself.

To interrupt the dream of Antigone, of the Antigonal subject of freedom and resoluteness, means to receive countless questions at the border to this impossible question in order to be responsible in a perhaps impossible sense. It means, within the horizon of a cheerfulness that is repeatedly reaffirmed, to risk an almost timeless hope by trying to dream the same dream somewhere else, under other conditions, with other qualifications, in a changed situation, more responsibly, more rigorously and more ruthlessly, to displace or drag the dream to where there is more hope of a response, of disenchanting, rationalizing or cooling off this dream of Antigone.

The new and different dreaming — would it remain the continuation of the original dream? Of that dream which one can call the dream of enlightenment, of emancipation and self-erection of the cogito or the transcendental subject, dream of light or day-dream, a dream distinguished by absolute restedness and wakefulness that is grounded on the figure of the prophet, the seer or visionary. Thus of that dream which dreams, in an impossible representation, for everybody by inventing the universal plan of a future expected in the collective in order to reduce every single subject with its dreams and hopes to its invention. Or doesn't this other Antigonal dreaming have to be more unique, more unrepeatable and more unshareable?

Who is dreaming when they are dreaming? And for whom? Can there be a subject of the Antigonal dream — non-prophetic and open to the future? Is Antigone dreaming or am I the one who dreams her, about her as the subject of her desire and her dream? Perhaps there is nothing more resistant than the pleasure of those dreamers who only sleep to be the impatient witnesses, authors or actors of the dreams of others. "What is a dream? And what is the thinking of the dream? And the language of the dream? Is there an ethics or a politics of the dream which gives way neither to the imaginary nor to Utopia and thus does not make itself guilty of any abdication, lack of responsibility or flight?"

It could be a matter of tearing the dream from the imaginary, the mere imagination and prophetic or authoritarian Utopias (Deleuze/Guattari), of making it responsible without defusing it and rationalizing it in a false sense. Does this demand something of the subject other than passing up the imaginary and the symbolic order ('reality') as the subject of an extraordinary dream? Antigone is dignified insofar as she is this raving dreamer, a girl who tries to protect herself against the symbolic imperatives and the temptations of the imaginary in order, in her poverty, nakedness and innocence, to develop a self-assured demand which is a kind of law of all the lawless, the 'law' of those who come into conflict with the law, are disadvantaged, misrecognized or excluded by it. Antigone's beauty is combined with her self-confident demand for a separate law for her always singular desire. This demand touches a certain impossibility; it captures the dimension of sacred life and endangered inviolability. Lacan's real is the name for this zone of interference and undecidability of the sacred or sublime with naked pre-ontological 'materiality'.

8. The political world

Derrida distinguishes three aporias of the political or the decision: 1) "the epoché of the rule" (any genuine decision is always also irregular, must always "make do without a rule"); 2) "visitation by the undecidable" (there is no decision without what is immanently undecidable in it); 3) "the urgency that blocks the horizon of knowledge" (for there to be a decision, the clarification of its conditions must be finite, i.e. limited and inadequate. There is no decision without it being precipitous).

One must not identify the political dimension which is the dimension of such a decision (of an ultimately uncontrollable and mad movement of the subject) with the state and its settled existence. In the state the possibility of an autonomous decision freezes; the state is apolitical in precisely this sense. Rancière writes, "Generally one employs the term politics for the totality of processes through which the unification and agreement of communities, the organization of powers, the distribution of offices and functions and the system of legitimation of this distribution take place. I propose that this distribution and the system of these legitimations be given another name. I propose that they be called the police".

The state is this machine of self-legitimation, i.e. in Rancière's terminology, the police. (Rancière himself distinguishes between state and police!) The state is indifferent in its interest. It "is indifferent or hostile to the existence of a politics that reaches for truth. ... In its essence the state is indifferent to justice. And conversely, any politics that is a thinking in actu causes, depending on its strength and duration, serious commotion in the state". Its indifference to justice, what Badiou calls the "egalitarian axiom", makes the state apolitical. It draws its sovereignty from this essential apoliticalness, from the subjectless administration of the established situation.

The subject bears responsibility for perhaps a new justice, for an axiom of justice. It practises its truth by making itself into the singular bearer of universal decisions. It decides in making decisions that imply a moment of imponderability or undecidability:

"A just, appropriate decision is always necessary immediately, at once, right away. It cannot first go about getting hold of infinite amounts of information, the limitless knowledge of the conditions, the rules, the hypothetical imperatives that could justify it. Even if it had such a knowledge, even if it took the necessary time to appropriate the necessary knowledge, despite this, the moment of decision, this moment as such would always be a finite moment of urgency and precipitancy, at least if one assumes that this moment cannot be and must not be the consequence or the effect of this theoretical or historical knowledge, of this reflection or cognitive consideration, and that this moment always represents an interruption to the juridical, ethical or political considerations which must and should precede it. The moment of decision is, as Kierkegaard writes, a madness."

The subject is the subject of this madness, agent of an overtaxation that demands of it to do what is almost impossible. It acts without being able to secure the ground and the telos of its action. It risks an essential precipitancy which infinitely singularizes all of its movements, "because singularity is properly speaking always there where the site of decision is located, and every decision as a true decision is ultimately a unique decision. Precisely speaking there is no general decision and insofar, that which introduces a truth or that which makes a truth obligatory or that which is supported by a fixed point belongs to the order of decision and thus belongs also a priori to the order of singularity".

To speak of a subject, no matter whether it be to deconstruct its modern form and its traditional predicates (self-consciousness, freedom, independence, autonomy, etc.) by demonstrating its transcendental derangement, or whether it be to confront it with the ineluctable obligation to judgement, resoluteness and its rational grounding, demands that the subject be thought as the arena of undecidable conflict between decisiveness and undecidability, autonomy and heteronomy, precipitancy and postponement. I call this conflict the war of différance.

With the concept of différance, Derrida does not articulate the simple postponement of decision, the limitedness and finiteness of the horizon of knowledge. Différance names the conflict of this postponement with the non-postponability of the decision so that one can say that postponement implies its own non-postponability and that non-postponability implies its own postponement. A common misunderstanding has led to Derrida being made into the philosopher of simple hesitancy and post-modern depoliticization. This misunderstanding, which is the result of a hasty reading of Derrida, can be made positive as an argument in favour of the deconstructive ethics of reading associated with the motif of postponement. At the same time one should not forget that urgency, non-postponability and precipitancy appear in all phases of Derrida's thinking not just as a 'necessary evil', but as structural features of the vectorial exaggeration, the hyperbolicalness of the (philosophical and deconstructive) subject (Derrida does not use the term 'subject'!).

The state sphere marks the apolitical space of a sovereignty which, whether democratic or not, concentrates on preventing illegitimate decision (but there is decision only beyond legitimation!), that is, on securing itself as the exclusive authority for decision. State sovereignty is therefore tautological. It is self-affective, whereas political sovereignty implies intervention in the state pleasure principle. Politics has made the bracketing of state sovereignty into the condition of its own existence as a sovereign practice of truth, that is, of its struggle for justice because "the modern state aims only at exercising certain functions or at achieving a consensus of opinion. According to its subjective dimension in makes do with transforming economic necessity, that is, the objective logic of capital, into resignation or resentment with the consequence that any programmatic or state definition of justice turns justice into its opposite. Justice then only makes an appearance as the harmonization of various interests".

If the interest of politics insofar as it defines itself as the politics of truth in Badiou's sense consists in the disinterested commitment to justice beyond interest, to justice as an axiom, then the political subject has to emancipate itself from the authority of the state. The responsibility associated with political sovereignty implies this emancipation of the political subject from state sovereignty which it understands as the restriction of political responsibility by norms. By accelerating the deceleration of subjective velocities in a frenetic thirst for justice, the state tries to outmanoeuvre the political forces which put its integrity as a distribution and equivalence machine into doubt.

In distinguishing two kinds of sovereignty, state sovereignty and political sovereignty, the conflict between territorializing (or reterritorializing) and deterritorializing power is also mirrored in the Deleuzian arrangement. The thinking of the vanishing point thinks itself as a political alternative to the apoliticalness of the system. It shows "that politics as thinking is not tied to the state and cannot be comprised or reflected in its state dimension. In a somewhat coarse formulation, this can also be said in a different way: the state does not think. This is a distinctive feature of the state".

For political sovereignty to be possible as a practice of thinking and thus as a practice of movement or deterritorialization, it has to free itself from the state in order to install its own model of justice. Only with this emancipation does the political subject appear as a subject, since in the act of renouncing the state paradigm, it liberates itself into the singularity of absolute sovereignty. Whereas state power is objectively comprehensive, political power can occur as a moment of absolute, i.e. unlimited freedom, without the political subject’s incorporation into the objective sphere of state and of the co-ordinates it administers being pushed aside. The political subject draws its sovereignty from the distance of absolute freedom from objective freedom. It constitutes itself in the resistance against the state and the norm it administers. "The state means sovereignty. But sovereignty rules only over that which it can interiorize, which it can spatially appropriate."

Political sovereignty at first expresses nothing other than the subject in freedom, a subject beyond the normative polis, a supra-political or apolitical, wild and amorphous, idiotic subject that tries to protect the truth of the political against the state's claims. As in Deleuzian materialist ontology as a whole, in the question concerning the political dimension in relation to the state apparatus it is also a matter of relations of velocity.

But philosophy cannot renounce the absolute. It needs the stimulation of what is urgent and non-deconstructable to resist not only the fathomless banality of commodity circulation, of nihilistic communicativeness, the capitalist abstraction of money and the universal preoccupation with security, but also the false figures of the sacred, of irreducible otherness and the divine. Therefore, as Badiou says, philosophy is concerned with erecting a certain "fixed point", with the indispensability of a truth which is the product of an assertion that is always singular.

9. Truth world

The hyperborean world is the world of truth as long as we understand by truth the zone of incommensurability, of the fighting out of the conflict between light and darkness, recollection and forgetting, opening and closure, aletheia and lethe. The hyperborean world of truth is the sphere of this conflict, the space of diaphora, which as hypo-, inter- and hyper-sphere borders the universe of facts on all sides. Diaphora is the Greek word for strife or primal strife, as Heidegger translates it. Diaphora outlines what is without outline, the immeasurable, the primordial disorder of beings in their uncountable diversity. Truth is therefore neither propositional truth, nor does it bend, like correctness (orthotes), to the law of countability, to calculus and calculation.

Truth as diaphora means nothing other than that which evades calculation from the outset, which makes calculation impossible and qualifies it as a making-impossible. The world of truth borders the space of calculability and values; it opens it through limitation by inscribing in it an infinite limit, an absolute overtaxing. The world of truth is the world of the impossible. The hyperborean subject enters this world not without a certain experience of loss. It risks its entire property, all of its capacities. It loses itself, its Self, in touching this exterior that destroys every certainty of identity.

A touching of truth always happens when the subject of this touching is forced to accelerate beyond its actual self, when it loses itself in contact with the non-contactable in the endless sea of undecidability. And yet, this losing of itself is anything but negative or arbitrary. The subject loses itself in order to constitute itself as the subject of self-loss, of the insecurity of identity. The subject of self-loss is the hyperborean subject of a touching of truth which at the same time includes self-constitution, self-invention and self-assertion. To touch the world of truth means to experience its limits and to affirm this experience of its own limitation as the opening up to another self. Truth-world is a name for the irreducible chaos, the pure nothingness of pure transcendental virtuality. The virtual is not illusory, and the transcendental is more than merely a naked structure. The transcendental dimension is, as Zizek emphasizes following Deleuze, the "infinite potential field of virtualities out of which reality actualizes itself". The world of truth is the world of transcendental virtualities, pre-ontological world of pure noumena which, in contradistinction to the actualized phenomena, have to be thought "not merely as appearances" (as positive ontological entities), "but as things in themselves". The thinking of noumena, insofar as it is only thinkable as an intellectual intuition independent of the receptiveness of the forms of sensuality, space and time, is a thinking of the unthinkable. To think the unthinkable is what we call a touching of truth; it is to make contact with the non-contactable, to touch the untouchable.

The hyperborean subject of truth is the subject of this hyperbolic touching. It over-stimulates its actual self in the transgression of its positive onto-historical identity toward the order of a truth that can only be touched and asserted. It transgresses the usual modalities of conventional philosophy such as reflection, argumentation, giving reasons, etc. toward the hyperbolic gesture of an impossible act. It is the assertion-subject of an assertion of truth in refusing the compulsions of the logic of facts, the calculus of the economy of facts, the pragmatism of the ethics of facts. It affirms itself as the subject of a thinking withdrawn from the imperatives of facts which is a thinking of the assertion and defence of truth.

The hyperborean subject is the hyperbolic subject of the love of truth. It loves, it asserts and it defends a truth which destabilizes its objective (socio-political, cultural, etc.) identity. This is what distinguishes it from the politicized subject of opinion. It denies itself the comfort and security of doxa in the loving assertion of truth, for the truth which this subject defends is anything but certain. Certainty (certitudo) exists only on the side of doxa, of sound common-sense and its images of itself and the world which are always conservative in their values.

What distinguishes truth from certainty is that it is as such deranged. The space of truth, of diaphora, of undecidability, of chaos, is the space of an irreducible, primordial derangement into which the subject finds itself admitted originarily. To be a subject means to put itself into an explicit relation to this truth which 'is' equally untruth, equally lethe (hiddenness) and aletheia (unhiddenness). It is this equally, this uncanny simultaneity and equality or "equiprimordiality of truth and untruth" which holds the subject in suspense from the outset. The subject of this monstrous simultaneity is the subject of restlessness. It experiences its being as the arena of this conflict-ridden unification of what cannot be unified, of the compossibility, the compatibility of death and life, beginning and end, origin and horizon.

The assertion and love of truth happen when the subject takes on the burden of this compossibility without making itself passive in relation to this ontological heritage. It is the drama of this inheritance which the subjects of opinion evade by privileging certainty before truth. To concede to certainty this ontological privilege means to allow the phantasma of some kind of harmony to take the place of this originary conflict. Certainty will always co-operate with a kind of obscurantism of self-tranquillization. It makes a coalition with the anxiety-ridden, sentimental or simply mystifying tendency of the subject of opinion to do everything possible to substitute the disturbing experience of undecidability (of truth, which is at the same time untruth) with some kind of construed idyll, with a metaphysics of self-tranquillization.

10. Diaphora

The essence of the subject lies in its transgression and surpassing of its essence. It corresponds to its essence by interrupting the logic of essence. The subject is the catastrophic subject of a primordial interruption. The "uncanniness" of the human subject, according to Heidegger, lies in the circumstance that the human being "is a katastrophé, a turning around, which turns it away from its own essence. The human being is within [the totality of] beings the unique catastrophe".

The catastrophe, the turn-over, the turn or the counter-swing, the turning against, or undecidable, as Derrida says, or the indistinguishable (Deleuze) prevent, as names for the essence of the human being, the possibility of determining its essence. The essence of the subject seems to lie therein, without being its determination of essence. The subject is separated from itself (from its essence, its being, its subjectivity) by an obviously irreducible distance. Subjectivity cannot be led back to the subject. The circumstance that the human being as subject is to deinotaton, the most uncanny being, refers to this ontological difference. It refers to the abyss between being and beings: physis, the event of propriation, beyng, the difference that holds sway, the diaphora. The subject is torn into this abyss. It is torn apart by it. It is the subject of a radical self-distancing. It is the distance and this abyss which holds it apart from its being (its subjectivity), which makes it almost nothing or allows it to reach into nothingness, into the abyss of its essence. The 'subjectivity' of the subject (without subjectivity) is nothingness.

The subject is too late, too early or delayed in relation to itself. "Always too late or ahead of time, in both directions simultaneously, but never on time," says Deleuze. It is the subject of absolute non-simultaneity, subject of a certain différance, of an irreducible deferral and conflict. It is not congruent with itself. It is not in agreement with itself. It is alien to itself. The human being is "not at home in its own essence," and therefore it is not a 'subject' in Heidegger's, Deleuze's and Derrida's thinking. It is scarcely still a subject insofar as the subject is understood as the transcendental subject of consciousness and self-consciousness of thinking in the modern age, the Cartesian fundamentum inconcussum, the Kantian transcendental subject, the concept conceiving itself of Hegel and German idealism in general. The subject of originary, non-subsequent (self-)alienation is a subject without transcendental accommodation. It is the subject of transcendental 'homelessness', subject without subjectivity, since its subjectivity is the name of this without.

11. Physis

Derrida has given special attention to the meaning of the verb 'hold sway' (walten) in Heidegger's thinking, especially in connection with Heidegger's engagement with Heraclitean polemos and the associated concept of violence. He has shown that in Heidegger's thinking, holding sway has a connection with diaphora, with a, so to speak, originary difference, with physis or the event of propriation as war or struggle, as abyss and withdrawal. In thinking the event of propriation or beyng (the belonging together of Dasein and being, their originary unity), Heidegger is at the same time compelled to think war or an irreducible power; the same Heidegger who says of the event of propriation that it is powerlessness and the very absence of violence itself.

The incipient power of physis is supposed to be powerlessness itself. The event of propriation is without violence and powerless, but it struggles with itself. The holding sway of the event of propriation "overpowers itself," says Derrida, "it triumphs over itself, is carried beyond itself within itself, ends up outside itself within itself. The power, force or violence of this holding sway is the originary physis which can only emerge in this self-overcoming of its own power."

The human being belongs to the event of propriation. It finds itself on the trajectory of death. Physis protrudes into human being in the form of withdrawal. What withdraws from the human being with physis is life as such, liveliness itself. The human being is the most uncanny being. The visitation of its being by the abyss of its death makes it into this. The human being is actively inclined toward this abyss. It points into withdrawal. As this sign it is subject. It is the subject of the "pointing" and, as Heidegger also says, the "saga" of this abyss. It is the subject of a monstrosity that surpasses it. The subject as subject is the name of this monstrous self-surpassing of the human being toward the real of a monstrosity which transcends it as subject.

12. The exterior

The hyperborean world of the real is what Foucault calls in his essay on Blanchot the "immeasurable space" touching origin and death or, as we say, the space of opening and closure, unconcealment (aletheia) and concealment or forgetting (lethe). "The pure exterior of the beginning, toward whose admittance language directs its attention, never consolidates itself into an immovable, transparent positivity; and the continually, newly begun exterior of death, which draws this forgetting that belongs to the essence of language into the light, does not have any border from where finally truth would become visible. The one constantly immediately turns into the other and vice versa; and death opens up over and over again the possibility of a renewed beginning."

The hyperborean subject experiences the real as the compossibility of the incompossible, the compatibility of the incompatible. The experience of this compossibility is the experience of the pure exterior which carries the subject into a strange zone alienated from any dialectic. To the point of indistinguishability, emergence and decline, origin and horizon meet one another in one and the same language: death and life immersed in one and "the same neutral light — light and dark at the same time". It is this logic of simultaneity of what is not simultaneous, this logic of indistinguishability, of the "mutual transparency of beginning and death," which the thinking of the exterior seems to share with the Heraclitean heritage of a non-dialectical contradictory fate.

Fragment 20 says of human beings and their relation to death and life: "Once born, they take it upon themselves to live and to have death — or rather, to rest — and they leave children behind so that new death is born."

Human beings are subjects of life and of death. They are subjects of the ontological compossibility of death and life. The Heraclitean logos is another name for this compossibility which is called to xynon in Fragment 2, which means not so much the general, but rather the common possible. The subject of life is already related to death. Living, it progenerates new life. With each of these acts of procreation, new death is born.

13. Différance

Différance resists itself. It implies a complicated resistance. Différance is the name for this resistance against classical ontology. Like Heidegger's being, it cannot be imagined as a being, an entity. Rather, it carries thinking to the extreme edge of its power of imagination and overtaxes thinking, to tear it into zones unknown to it. More than the traces of being, différance bears traits of granting, that is, of that which 'is' without belonging to the positive order of being. "Différance is not. It is not any present being, no matter how outstandingly unique, fundamental or transcendent one would like it to be. It does not rule anything or hold sway over anything and does not exercise any authority at all."

Derrida calls différance a difference that does not belong to the system of identity-difference. The différance is not the negative that helps a positive to a mediation with itself. The thinking of différance is neither negative nor dialectical, nor speculative. It refers to a game that withdraws from the dialectical work of negation in every respect. The différance opens up in the first place the room for play of conceptual work and the binary oppositions which organize it. It opens it up by withdrawing from it, by not being able itself to correspond to the rules of the game which it has opened, for its own game, the game of différance, corresponds to irregularity itself. With it reference is made "to an order that resists the opposition between the sensible and the intelligible that is fundamental for philosophy. ... The concept of game keeps itself beyond this opposition; it announces in the night-watch before philosophy and beyond it the unity of contingency and necessity in a calculus without end".

Différance withdraws, it refuses, it resists the metaphysics of presence. It is a kind of irreducible, i.e. resistant, non-presence, abyss of any presence which itself is conceivable neither as presence nor as a present absence. The game of this abyss which we, along with Heraclitus, Nietzsche and Heidegger, call the game of the world, is called by Derrida the game of différance. The différance opens up the room for play of that which Heidegger calls Western metaphysics and Derrida the history of logocentrism. From the beyond of occidental onto-theology, the game of différance controls the productivity, the differentiations, the identifications, the taxonomies and typologies of a tradition oriented toward the model of presence with its concept of living presence (ousía). It is the 'origin' of metaphysics, 'origin' of the logos which itself is nothing but the origin of the metaphysical movement of thought. Différance can therefore no longer be called origin. It is the "non-full, non-simple origin of differences. Consequently, the name 'origin' can no longer be applied to it".

The thinking of différance must be thought as the thinking of the 'origin' of the origin. It points into the abyss of logocentrism; it opens thinking to a space beyond the logos, beyond ratio, certitudo, self-consciousness insofar as the latter imagines itself as pure self-affection. It is a thinking that refuses to decide between the alternatives of uncertainty (expectation, hope) and certainty (calculation, calculus), between opening and closure, by holding open the gap (the difference) between these options. It decides in favour of the conflict between all the metaphysical options that depend on the model of presence/absence: activity/passivity, culture/nature, subject/object, etc., that is, in favour of the conflict which Heidegger addresses as the primal conflict between aletheia and lethe or, as Derrida also calls différance, in favour of primal violence, arche-violence.

14. Chora

The subject opens itself to a desert which is like the Platonic chora: a pre-originary 'place', an impossible 'origin' of the origin of the Western logos, a place, "more anarchic than any other place, ... not an island or promised land, a certain desert which is not the desert of revelation, but a desert in the desert, a desert that enables the desert, opens it, digs it, hollows it out, extends it into infinity".

Chora is the name of that which is without properties and without gender, which remains nameless and cannot be appropriated because it opens up the space of predicative positing and ontological attribution in the first place, keeping it open and "arranging the space" (einräumt, Heidegger) without being able to itself belong to this space of opening up. Chora is the "locus of an infinite resistance," of an absolute incommensurability and namelessness which Derrida calls "conscienceless", the "no longer thinkable desert in the desert to which no threshold leads". The distinction between the "desert of revelation" and this "desert in the desert" is articulated in Heidegger as the conflict between openness (or opened-up-ness) and its closure or disablement in the structure of the event of propriation as the dimension of both the granting and denying of being. It is articulated in withdrawal insofar as this refers to the collapse of truth, of aletheia, of the openness of the Da in my own individual death.

At the same time, Heidegger presupposes in the fundamental on