Roger Ballen / Ryan Mendoza / Paul P.

05 Jun - 26 Jul 2013

ROGER BALLEN / RYAN MENDOZA / PAUL P.

5 June - 26 July 2013

This Is a Working Title (The Exhibition as Explained to Tommaso)

Tommaso is a beautiful little boy, just six months old. He has an attentive gaze and a devastating smile. His grandfather Massimo, well acquainted with his precocious intelligence, is convinced that you could even talk to him about an art exhibition, the works on display, the lives of the artists, the whys and wherefores. “Like a fairy tale,” he says, amused by how obvious the idea is. And that’s what he’s asked me to do. I’m afraid he’s rather overestimating my abilities, because this definitely a complex exhibition.

Dear Tommaso,

First of all, you should know that a mostra [exhibition] is not a female mostro [monster], even though to be good, it needs to have some aspect that’s monstrous, that is, something out of the ordinary. Actually, an exhibition is an odd assortment of strange images, thought up by artists. Now, please, don’t ask me why artists come up with them and why people want to see them, otherwise this will get too long and I’ll get lost. So, moving along.

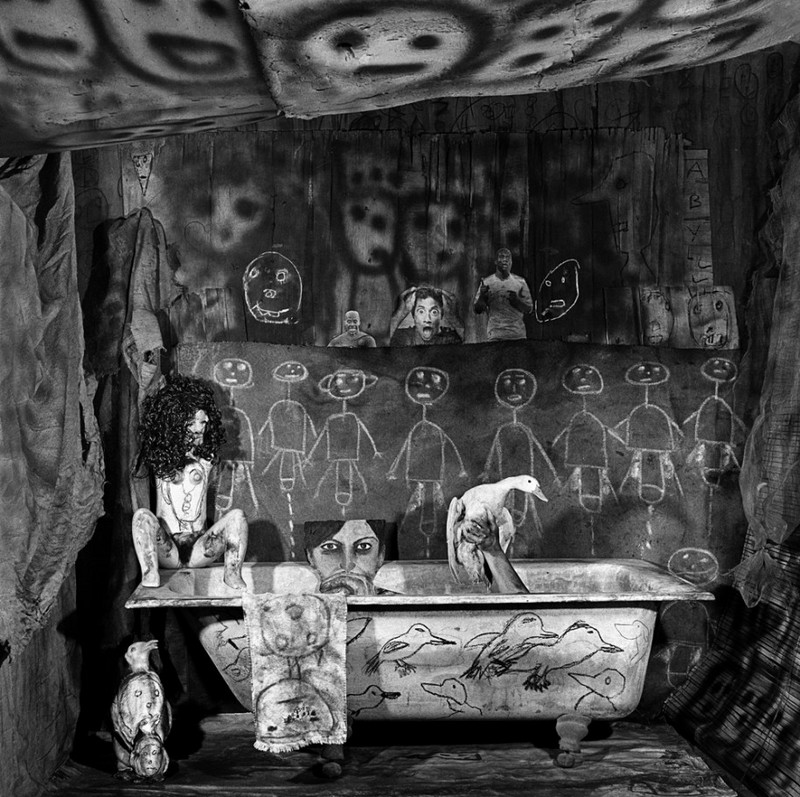

Three artists, named Roger Ballen, Ryan Mendoza, and Paul P., have been brought together in this exhibition. These three gentlemen come from faraway countries, they're from different generations and backgrounds, and they make works that are very different from each other. The first is a photographer. He takes pictures with a camera that can only see in black and white. His photographs show objects, masks, drawings, animals, toys, plants, pieces of wire, stains on the walls, graffiti, and above all, people, mixed up with all the rest. But the curious thing is that they’re always inside a room, as if that were their only space and there were nothing else outside it. If you were a less perceptive person—like me, for instance—I’d try to explain it to you in simpler terms and say that it's a claustral universe, a Huis clos, in which the isolation of the human figure refers to the deeper realm of consciousness, where our reflection teeters between dreams and reason, and is not at all comforting, hence is authentic. But I know there’s no need, you’ve already figured that out for yourself. Instead, what I absolutely must tell you is that Roger Ballen is also a geologist, and spent years working in the mines of South Africa. Mines are places underground, made of shafts and tunnels that stretch toward the center of our planet, cutting through layers of minerals that keep changing the deeper you go. They’re sort of like the Earth's memory, because inside them are all the things that have accumulated since the dawn of time. They’re very similar to our brains, which are also made of endless circuits, and in which we all store images from our lives, whether they’re things we've seen or things we’ve imagined. Well, Mr. Ballen’s camera works like a drill, bringing memories, dreams, fantasies and nightmares to the surface. And he examines them like those stones that are grey on the outside, but when you break them open, are full of amazing patterns that look like paintings. I’m sure that if your grandfather Massimo had been thinking of this exhibition like a house to be built, he would have assigned the task of digging and laying the foundations, the underground part where the cellar is, to Ballen. Once you learn to walk, you’ll find out how wonderful it is to explore a cellar, especially one that’s crammed with old furniture, dusty paintings, mysteriously labelled bottles, bundles of magazines with surprising covers, broken playthings, and maybe a mouse smirking out at you ominously from underneath a cracked bowl. Half frightened and half delighted, you’ll discover what courage is and feel the thrill of imagination and amazement. By yourself, face to face with your thoughts.

I think we’ve arrived at our first idea. We could say this is the story of an exhibition that’s built like a house. And maybe we’re also moving towards a somewhat less provisional title. It could be “Tommaso's House” (not yet a definitive title). In Tommaso’s house, the cellar has been built by Roger Ballen to resemble a mine. It is painted in infinite shades of grey, that is, in black and white, like South Africa. Which is the world’s cellar, if New York is its penthouse. It’s an underground space you must visit on your own, because all there is to see, underneath the dust, among the images that teem within it, is really just yourself.

Obviously, we can already hear an echo of the rumpus upstairs. People coming in, sitting down, chatting, getting up, drinking, laughing, going out again; there's even music. Of course, that’s the ground floor, the one giving onto the street where everybody walks by. Coming and going. Inside and out. That is where Ryan Mendoza lives and works, having escaped to Naples; he too is originally from New York. He’s a painter and this is his studio. There’s quite a stir, his wife, his wife’s friends, the male and female models, but you never see him. We’re sure he’s around, though, since his paintings show the people who are there. Alone, in couples, sometimes full-figure, sometimes transparent. They’re looking towards him as if they’d just noticed they’re being spied on through the keyhole. And maybe they are. They’re inside the paintings and give the impression that they can’t get back out. Tangled up in a setting gorged with light and color, lamps, fabrics, wallpaper, furniture and bibelots. But also caught in the painter’s gaze, which devours them after capturing them in a moment of weakness, like a carnivorous plant with the insects it feeds on. Cruel, but without malice; rather, with the tenderness that is due to one’s pathetically struggling prey in the moment before it succumbs.

You see, Tommaso—and I’m saying this more to explain it to myself as to you—it’s almost as if this artist were looking at the world from his seat at a peepshow. That is, in a little private theater where he’s sitting on one side of the glass, watching a pretty girl on the other as she earns the price of the ticket by wriggling around artfully for a few minutes, until the light goes off. What unites them is his gaze; what seems to separate them is the solitude of each; but actually, they are accomplices in the same scheme, one they know by heart, which consists in penetrating someone else’s life with one’s gaze, before it all disappears behind the glass. Of course, I'll spare you the linguistic flourishes about the polysemy of the verb "to penetrate" and the similarities between the lexicons of painting and eroticism, or the endless observations one could make about the tug-of-war between love and death in the genesis of an artwork.

These are matters better left to the erudite people whom Massimo also finds so boring. What really interests us for our purposes is that on the ground floor of this house, there is the work of Ryan Mendoza, because these paintings full of sensuality and emotion are intense gazes, resting on bodies that are desired and perhaps even loved. As if to make them his own before the street out there swallows them up again. As if painting were the only crowbar capable of breaking the glass that separates him from them.

And with this, I’d say the story gains a second chapter. The house, which is an exhibition, has a ground floor with the ochre and pink of the baroque buildings that line the streets of Naples. With the dense flesh of young women, the fleeting forms of their unripe bodies. Now the title could be “Tommaso Goes Outside” (title to be determined). And it’s very likely that, in some not-too-distant future, the inner turmoil set in motion by an insistent gaze will open the doors of the world for you. Whether it’s called love or painting doesn’t really matter, it’s definitely the best way to enter. This floor of the house, of course, is one you visit with another person.

The last floor is as cocoon-like as the vast north of Canada, a country I’ve never been to. But I can imagine it. Swaddled in sky and snow, much like Norway. Which is another country I’ve never been to. Because I’ve travelled a lot in my life, but mostly within my own home. I’ve visited its northernmost frontier and am well acquainted with its attic, the place closest to the clouds, which are merely a celestial reflection of the snow. When I was not much older than you, I told myself that if I was an angel that’s where I would want to live, in the attic. So as not to be too far away from my former home. And I’m sure that angels really do live there, in the sunlight cutting through the gray air that flows in from the dormer windows. So far away from the telluric rumbling of the cellar and the social hubbub of the street level, in what has always seemed to me like the locus of silence and meditation, perhaps of melancholy.

The attic of Tommaso’s house is full of paintings and etchings by Paul P., a Canadian artist who lives in Paris. And I’d love to tell you how much these little canvases and delicate sheets of paper remind me of the suspended, almost abstract atmospheres of some masters of the past. The chilly landscapes by Munch, the foggy lagoon by Whistler, the gauzy figures by Sargent: But only because at this point in life, it's almost impossible to look at paintings without thinking of other paintings. A pitfall of old age. The fact is that these androgynous bodies, bathed in the dim colors and shimmering light of the heure bleue, caught up in the evocation of a distant, invisible elsewhere, are those of angels. Yes, angels: disincarnate presences, delicate spirits flitting between heaven and earth, intangible images made of air and light. To paint their portrait you must imagine them, because they do not allow themselves be seen, let alone are they inclined to pose. They are ideas, figures of the mind, expressions of the soul. And if you’ll pardon the silly pun, they must be caught on the fly. With the speed of thought, as we are told by Aristotle, a gentleman over two thousand years old, because “the soul never thinks without an image”. That’s just it: these figures and landscapes are thoughts that let us see what our eyes cannot until they close, until they stop looking outside and come to rest on the other sky within us. In silence.

The story of the exhibition is coming to an end, and with it, our tour of the house. Thanks to Paul P., we also have an attic, empty at first glance, but actually overflowing with things to see. His colors are those of water, air, clouds, snow, light, dawn and dusk. The colors of the north, soft and subdued. Between the bluish white of Canada and the rainy gray of Paris. At this point, our title could be “Painting Is a House in the Mind” but in the end I’d rather keep “This Is a Working Title” as the definitive one, because we could also have called this story “The Mind is a Thing of Pictures” or a hundred other titles. What’s important to me, Tommaso, is that you know I haven’t made all this up from scratch; it was suggested to me in part by Massimo and in part by a French gentleman named Gaston Bachelard, whereas the title is the work of my friend Corrado. But above all, that from now on, you can tell this story too, any way you like.

Didi Bozzini

February 2013

5 June - 26 July 2013

This Is a Working Title (The Exhibition as Explained to Tommaso)

Tommaso is a beautiful little boy, just six months old. He has an attentive gaze and a devastating smile. His grandfather Massimo, well acquainted with his precocious intelligence, is convinced that you could even talk to him about an art exhibition, the works on display, the lives of the artists, the whys and wherefores. “Like a fairy tale,” he says, amused by how obvious the idea is. And that’s what he’s asked me to do. I’m afraid he’s rather overestimating my abilities, because this definitely a complex exhibition.

Dear Tommaso,

First of all, you should know that a mostra [exhibition] is not a female mostro [monster], even though to be good, it needs to have some aspect that’s monstrous, that is, something out of the ordinary. Actually, an exhibition is an odd assortment of strange images, thought up by artists. Now, please, don’t ask me why artists come up with them and why people want to see them, otherwise this will get too long and I’ll get lost. So, moving along.

Three artists, named Roger Ballen, Ryan Mendoza, and Paul P., have been brought together in this exhibition. These three gentlemen come from faraway countries, they're from different generations and backgrounds, and they make works that are very different from each other. The first is a photographer. He takes pictures with a camera that can only see in black and white. His photographs show objects, masks, drawings, animals, toys, plants, pieces of wire, stains on the walls, graffiti, and above all, people, mixed up with all the rest. But the curious thing is that they’re always inside a room, as if that were their only space and there were nothing else outside it. If you were a less perceptive person—like me, for instance—I’d try to explain it to you in simpler terms and say that it's a claustral universe, a Huis clos, in which the isolation of the human figure refers to the deeper realm of consciousness, where our reflection teeters between dreams and reason, and is not at all comforting, hence is authentic. But I know there’s no need, you’ve already figured that out for yourself. Instead, what I absolutely must tell you is that Roger Ballen is also a geologist, and spent years working in the mines of South Africa. Mines are places underground, made of shafts and tunnels that stretch toward the center of our planet, cutting through layers of minerals that keep changing the deeper you go. They’re sort of like the Earth's memory, because inside them are all the things that have accumulated since the dawn of time. They’re very similar to our brains, which are also made of endless circuits, and in which we all store images from our lives, whether they’re things we've seen or things we’ve imagined. Well, Mr. Ballen’s camera works like a drill, bringing memories, dreams, fantasies and nightmares to the surface. And he examines them like those stones that are grey on the outside, but when you break them open, are full of amazing patterns that look like paintings. I’m sure that if your grandfather Massimo had been thinking of this exhibition like a house to be built, he would have assigned the task of digging and laying the foundations, the underground part where the cellar is, to Ballen. Once you learn to walk, you’ll find out how wonderful it is to explore a cellar, especially one that’s crammed with old furniture, dusty paintings, mysteriously labelled bottles, bundles of magazines with surprising covers, broken playthings, and maybe a mouse smirking out at you ominously from underneath a cracked bowl. Half frightened and half delighted, you’ll discover what courage is and feel the thrill of imagination and amazement. By yourself, face to face with your thoughts.

I think we’ve arrived at our first idea. We could say this is the story of an exhibition that’s built like a house. And maybe we’re also moving towards a somewhat less provisional title. It could be “Tommaso's House” (not yet a definitive title). In Tommaso’s house, the cellar has been built by Roger Ballen to resemble a mine. It is painted in infinite shades of grey, that is, in black and white, like South Africa. Which is the world’s cellar, if New York is its penthouse. It’s an underground space you must visit on your own, because all there is to see, underneath the dust, among the images that teem within it, is really just yourself.

Obviously, we can already hear an echo of the rumpus upstairs. People coming in, sitting down, chatting, getting up, drinking, laughing, going out again; there's even music. Of course, that’s the ground floor, the one giving onto the street where everybody walks by. Coming and going. Inside and out. That is where Ryan Mendoza lives and works, having escaped to Naples; he too is originally from New York. He’s a painter and this is his studio. There’s quite a stir, his wife, his wife’s friends, the male and female models, but you never see him. We’re sure he’s around, though, since his paintings show the people who are there. Alone, in couples, sometimes full-figure, sometimes transparent. They’re looking towards him as if they’d just noticed they’re being spied on through the keyhole. And maybe they are. They’re inside the paintings and give the impression that they can’t get back out. Tangled up in a setting gorged with light and color, lamps, fabrics, wallpaper, furniture and bibelots. But also caught in the painter’s gaze, which devours them after capturing them in a moment of weakness, like a carnivorous plant with the insects it feeds on. Cruel, but without malice; rather, with the tenderness that is due to one’s pathetically struggling prey in the moment before it succumbs.

You see, Tommaso—and I’m saying this more to explain it to myself as to you—it’s almost as if this artist were looking at the world from his seat at a peepshow. That is, in a little private theater where he’s sitting on one side of the glass, watching a pretty girl on the other as she earns the price of the ticket by wriggling around artfully for a few minutes, until the light goes off. What unites them is his gaze; what seems to separate them is the solitude of each; but actually, they are accomplices in the same scheme, one they know by heart, which consists in penetrating someone else’s life with one’s gaze, before it all disappears behind the glass. Of course, I'll spare you the linguistic flourishes about the polysemy of the verb "to penetrate" and the similarities between the lexicons of painting and eroticism, or the endless observations one could make about the tug-of-war between love and death in the genesis of an artwork.

These are matters better left to the erudite people whom Massimo also finds so boring. What really interests us for our purposes is that on the ground floor of this house, there is the work of Ryan Mendoza, because these paintings full of sensuality and emotion are intense gazes, resting on bodies that are desired and perhaps even loved. As if to make them his own before the street out there swallows them up again. As if painting were the only crowbar capable of breaking the glass that separates him from them.

And with this, I’d say the story gains a second chapter. The house, which is an exhibition, has a ground floor with the ochre and pink of the baroque buildings that line the streets of Naples. With the dense flesh of young women, the fleeting forms of their unripe bodies. Now the title could be “Tommaso Goes Outside” (title to be determined). And it’s very likely that, in some not-too-distant future, the inner turmoil set in motion by an insistent gaze will open the doors of the world for you. Whether it’s called love or painting doesn’t really matter, it’s definitely the best way to enter. This floor of the house, of course, is one you visit with another person.

The last floor is as cocoon-like as the vast north of Canada, a country I’ve never been to. But I can imagine it. Swaddled in sky and snow, much like Norway. Which is another country I’ve never been to. Because I’ve travelled a lot in my life, but mostly within my own home. I’ve visited its northernmost frontier and am well acquainted with its attic, the place closest to the clouds, which are merely a celestial reflection of the snow. When I was not much older than you, I told myself that if I was an angel that’s where I would want to live, in the attic. So as not to be too far away from my former home. And I’m sure that angels really do live there, in the sunlight cutting through the gray air that flows in from the dormer windows. So far away from the telluric rumbling of the cellar and the social hubbub of the street level, in what has always seemed to me like the locus of silence and meditation, perhaps of melancholy.

The attic of Tommaso’s house is full of paintings and etchings by Paul P., a Canadian artist who lives in Paris. And I’d love to tell you how much these little canvases and delicate sheets of paper remind me of the suspended, almost abstract atmospheres of some masters of the past. The chilly landscapes by Munch, the foggy lagoon by Whistler, the gauzy figures by Sargent: But only because at this point in life, it's almost impossible to look at paintings without thinking of other paintings. A pitfall of old age. The fact is that these androgynous bodies, bathed in the dim colors and shimmering light of the heure bleue, caught up in the evocation of a distant, invisible elsewhere, are those of angels. Yes, angels: disincarnate presences, delicate spirits flitting between heaven and earth, intangible images made of air and light. To paint their portrait you must imagine them, because they do not allow themselves be seen, let alone are they inclined to pose. They are ideas, figures of the mind, expressions of the soul. And if you’ll pardon the silly pun, they must be caught on the fly. With the speed of thought, as we are told by Aristotle, a gentleman over two thousand years old, because “the soul never thinks without an image”. That’s just it: these figures and landscapes are thoughts that let us see what our eyes cannot until they close, until they stop looking outside and come to rest on the other sky within us. In silence.

The story of the exhibition is coming to an end, and with it, our tour of the house. Thanks to Paul P., we also have an attic, empty at first glance, but actually overflowing with things to see. His colors are those of water, air, clouds, snow, light, dawn and dusk. The colors of the north, soft and subdued. Between the bluish white of Canada and the rainy gray of Paris. At this point, our title could be “Painting Is a House in the Mind” but in the end I’d rather keep “This Is a Working Title” as the definitive one, because we could also have called this story “The Mind is a Thing of Pictures” or a hundred other titles. What’s important to me, Tommaso, is that you know I haven’t made all this up from scratch; it was suggested to me in part by Massimo and in part by a French gentleman named Gaston Bachelard, whereas the title is the work of my friend Corrado. But above all, that from now on, you can tell this story too, any way you like.

Didi Bozzini

February 2013