Body Performance

30 Nov 2019 - 20 Sep 2020

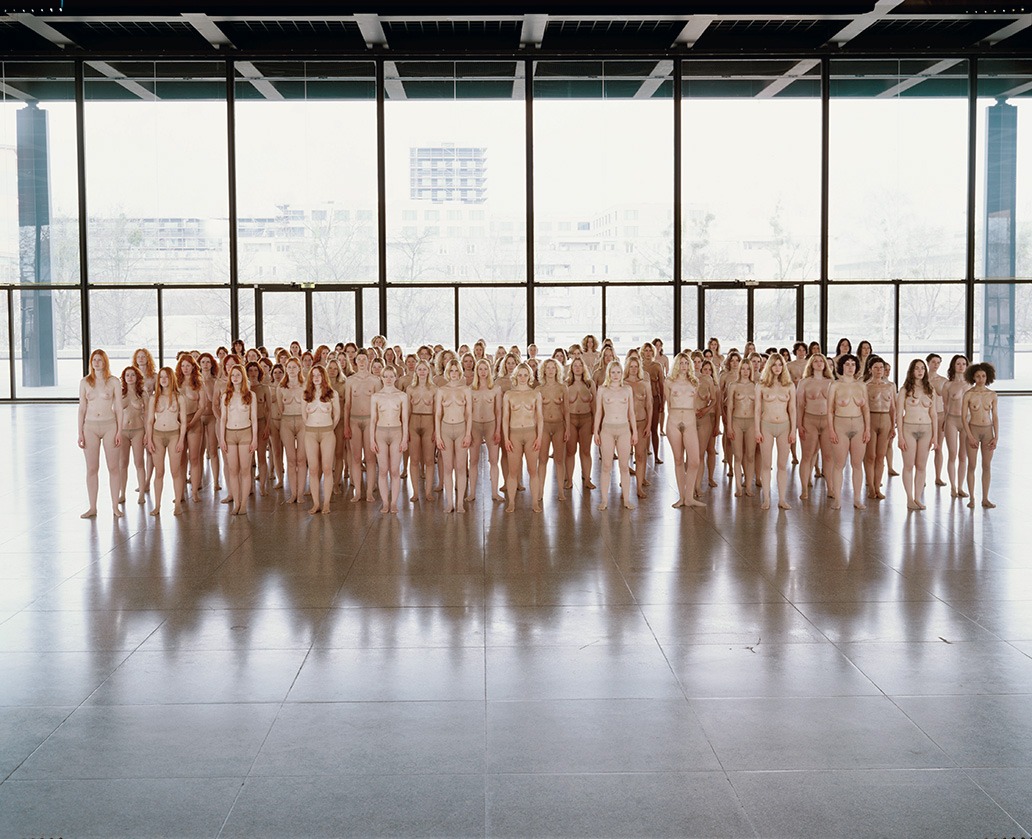

Vanessa Beecroft, VB55 - Performance, VB55.004.NT, Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin, 2005 © Vanessa Beecroft

BODY PERFORMANCE

30 November 2019 – 20 September 2020

Performance is an independent art form and photography is its constant companion. Human actions in front of the camera can be conscious or unconscious, choreographed or accidentally observed. For the first time, this group exhibition brings together photo sequences whose origins lie in performance art, dance, and other staged events, complemented by conceptual photography series. With their common focus on the human body, the images document or interpret performances, which in many cases have also been initiated by the photographers themselves.

One relatively unknown work by Helmut Newton is the series of images he made of the dancers of the Monte Carlo Ballet. Taken over many years, the photos were intended for print in the theater’s program booklets and special publications, and Newton only had a few of the motifs enlarged for inclusion in his own exhibitions. His series is the starting point and core of this group show. Slipping into the role of a theater director, he accompanied the dancers on the streets of Monaco, on the steps behind the famous casino, near an emergency exit of the theater, or in the nude at his own home. With Les Ballets de Monte Carlo, he therefore reinterpreted a compositional idea that came to define his work – Naked and Dressed.

We also encounter this connection in the work of Bernd Uhlig, who has photographically accompanied the choreographies by Sasha Waltz for many years. These have not only been performed in classical theaters but also in renowned museums in Berlin and Rome, among others, sometimes taking place in their stairwells. In the collaboration of Bernd Uhlig and Sasha Waltz, a genuinely fleeting art form and its visual materialization find a congenial connection, in which the focus is on the performers’ concentration and dream or trance states. While Uhlig’s earlier (analogue) works used longer exposures to capture movement resulting in motion trails, here he shows us close-ups of frozen gestures on the one hand, and the entire stage choreography captured in a split second on the other.

Vanessa Beecroft presents nude or clothed women in elaborate tableaux vivants, frequently staged in galleries or museums, usually as public events. The women, often a few dozen, stand arranged in a formation of sorts, and during the hours-long actions their movements occur in slow motion. Actually, barely anything happens during the minimalist choreography. Beecroft photographically documents this state of moving motionlessness, and the numerous images of the performance transport the process into the static image. Here we see her performance VB55, presented at Berlin’s Neue Nationalgalerie in 2005, as life-size photographs. Beecroft identifies with her protagonists: they become a multiple alter ego, of whom she demands only a natural facial expression and a similarly natural posture.

In his multi-part Viva España series from 1976, Jürgen Klauke allowed only two people to interact: a man and a woman engaged in a mysterious dance on a dark stage. Typical of certain Spanish and South American dances, this dance is also imbued with a touch of seduction or eroticism. Of the two protagonists, we only see their anonymous bodies: while the man remains standing, the woman whirls or is whirled around him, upside-down. Viewing the sequence in succession, however, gives the illusion of movement. Klauke allows the clothed and semi-clothed bodies of the man and woman to apparently melt into one another. In doing so he blurs the line between feminine and masculine, which he also did in a similar way in numerous self-portraits he took of himself in drag around the same time.

Erwin Wurm goes a step further than Klauke in terms of absurd humor, when he asks people for a mini performance in front of the camera. For his One Minute Sculptures, people interact with objects to transform the street and various interiors into a stage. Wurm thinks up curious poses or absurd contortions for the collaborators, he provides clear and simple directions, thus issuing the signal to translate the performative action back into static photographs. Attempts to lie on narrow surfaces, to stick one’s head into a wall, or to balance two cups on one’s feet in the air while lying supine, are not always successful. Of course, anyone who allows themselves to be drawn into this unusual artistic experiment must confront their own physical limitations as well as their boundaries of modesty.

For years, Barbara Probst has surprised viewers with her own playfully experimental blend of classical street photography, portraiture, still life and, more recently, fashion. She arranges her photographs into diptychs, triptychs, and occasionally into wall-sized tableaux consisting of a dozen individual images. They always bear the same title – Exposures – and are distinguished with an image number along with the location and date of the shoot. The date is indicated to the day and exact minute. She photographs the same situation with several cameras from different angles at the same time, triggered at exactly the same moment by radio waves. The simultaneous multiple perspectives captured by the cameras is then flattened, so to speak, once they are hung on the walls of the exhibition space.

Viviane Sassen also works mainly with the human body. She sometimes captures it in extreme contortions for her experimental fashion images. She choreographs and stages her model’s bodies in unexpected ways, for example by coloring their skin or depicting them obscured by shadow, mirrored, superimposed by objects, and often abstracted by cropping or framing the images. Occasionally she inverts the generally valid order of above and below, which results in a sense of disorientation for the viewer. Sassen challenges us as viewers and raises questions about common clichés. As a former model, she knows both sides, in front of and behind the camera. As she once stated in an interview, it is through her own photographic works that she has been able to reclaim power over her own body.

Since the 1990s, Inez & Vinoodh have been irritating the world of fashion since the 1990s with surreal images. Their techniques include digital image manipulation, which they use to fuse the bodies of men and women. Inez & Vinoodh not only push the boundaries of common modes of representation but also the limits of reality. At other times, they have radically altered or combined the sexes and skin colors of their protagonists. As such, their images embody the transgression of boundaries, and this connects them to Newton’s earlier strategy of questioning “good taste” and subtly but intentionally challenging it visually “from within the system.” They likewise shoot magazine editorials and work directly with a number of famous designers, and count among the most influential contemporary photographers with their iconic imagery.

We also encounter a sense of ambiguity in the work of Cindy Sherman. In her early, small-format black-and-white series Untitled Film Stills from the late-1970s, she slips into ever-new roles like an actress. Despite appearing to be unspectacular observations from everyday life, they are actually deliberately staged, with the artist as the main character. Sherman continued the idea of role playing in her work, later disguising herself behind thick layers of make-up and wigs, masks, or breast prostheses in her colorful, untitled self-portraits from the year 2000. Her games of transformation, camouflage, and representation naturally include many cinematic references – some portraits have the explicit feel of film stills, featuring an aging actress starring in a movie that has yet to be made.

Yang Fudong’s black-and-white photography is also inspired by the medium of film, specifically by film noir of the 1960s and even earlier films from Shanghai. Fudong seems to invoke a timeless past with his nude photographs tinged with melancholy; in his films, as well, we encounter narratives that are similarly imbued with a sense of mystery. Such an open show of nudity is still considered a provocation in large parts of Chinese society today. In Fudong’s New Women series, one or more nude women sit or stand in a sparsely but luxuriously equipped studio set. The female models – in both the static images and the film – are reminiscent of Brassaï’s portraits of prostitutes from Paris in the 1930s, which were an important source of inspiration for Newton’s later, ambivalent fashion photographs. The exhibition Body Performance thus closes the circle by means of myriad approaches across different cultures and times.

It was in the 1970s that Robert Longo shot his photo sequence Men in the Cities on the roof of a high-rise building in New York City, which he later reinterpreted as large-format charcoal drawings. In these images we see people caught by the camera in unnatural poses. They appear to be dancing wildly, or replaying scenes from American western, war, or gangster films – for example, when someone seems to fall in a hail of imaginary bullets. In fact, it was such a film still from Fassbinder’s The American Soldier from 1970 that inspired Longo to create this series of performative images. On the roof of his loft, his models dodged objects that were swinging around or thrown at them, while Longo photographed them falling to the ground or lying there contorted.

Robert Mapplethorpe, on the other hand, choreographed only one person in the image presented here: the former bodybuilding world champion, Lisa Lyon, who referred to herself as a sculptor of her own body. We see her lying nude on a boulder in Joshua Tree National Park in California, in 1980. The rock’s hard surface contrasts with her soft skin, while its massive strength corresponds to Lyons’s muscular legs. In this unconventional open-air setting, Mapplethorpe presents us with a ballet-like choreography. Everything can become a stage – an interplay between seeing and being seen. At around the same time, Newton worked with Lyon in California and Paris. With this “strong woman” in the truest sense of the word, another circle closes in the current exhibition Body Performance.

In this exhibition, we encounter role play and physical transformation as contemporary photographic perspectives on the most diverse visual aspects of the body and movement. As we view these images, questions come into focus concerning how we are perceived by others and by ourselves, identity, and the collective.

Matthias Harder

30 November 2019 – 20 September 2020

Performance is an independent art form and photography is its constant companion. Human actions in front of the camera can be conscious or unconscious, choreographed or accidentally observed. For the first time, this group exhibition brings together photo sequences whose origins lie in performance art, dance, and other staged events, complemented by conceptual photography series. With their common focus on the human body, the images document or interpret performances, which in many cases have also been initiated by the photographers themselves.

One relatively unknown work by Helmut Newton is the series of images he made of the dancers of the Monte Carlo Ballet. Taken over many years, the photos were intended for print in the theater’s program booklets and special publications, and Newton only had a few of the motifs enlarged for inclusion in his own exhibitions. His series is the starting point and core of this group show. Slipping into the role of a theater director, he accompanied the dancers on the streets of Monaco, on the steps behind the famous casino, near an emergency exit of the theater, or in the nude at his own home. With Les Ballets de Monte Carlo, he therefore reinterpreted a compositional idea that came to define his work – Naked and Dressed.

We also encounter this connection in the work of Bernd Uhlig, who has photographically accompanied the choreographies by Sasha Waltz for many years. These have not only been performed in classical theaters but also in renowned museums in Berlin and Rome, among others, sometimes taking place in their stairwells. In the collaboration of Bernd Uhlig and Sasha Waltz, a genuinely fleeting art form and its visual materialization find a congenial connection, in which the focus is on the performers’ concentration and dream or trance states. While Uhlig’s earlier (analogue) works used longer exposures to capture movement resulting in motion trails, here he shows us close-ups of frozen gestures on the one hand, and the entire stage choreography captured in a split second on the other.

Vanessa Beecroft presents nude or clothed women in elaborate tableaux vivants, frequently staged in galleries or museums, usually as public events. The women, often a few dozen, stand arranged in a formation of sorts, and during the hours-long actions their movements occur in slow motion. Actually, barely anything happens during the minimalist choreography. Beecroft photographically documents this state of moving motionlessness, and the numerous images of the performance transport the process into the static image. Here we see her performance VB55, presented at Berlin’s Neue Nationalgalerie in 2005, as life-size photographs. Beecroft identifies with her protagonists: they become a multiple alter ego, of whom she demands only a natural facial expression and a similarly natural posture.

In his multi-part Viva España series from 1976, Jürgen Klauke allowed only two people to interact: a man and a woman engaged in a mysterious dance on a dark stage. Typical of certain Spanish and South American dances, this dance is also imbued with a touch of seduction or eroticism. Of the two protagonists, we only see their anonymous bodies: while the man remains standing, the woman whirls or is whirled around him, upside-down. Viewing the sequence in succession, however, gives the illusion of movement. Klauke allows the clothed and semi-clothed bodies of the man and woman to apparently melt into one another. In doing so he blurs the line between feminine and masculine, which he also did in a similar way in numerous self-portraits he took of himself in drag around the same time.

Erwin Wurm goes a step further than Klauke in terms of absurd humor, when he asks people for a mini performance in front of the camera. For his One Minute Sculptures, people interact with objects to transform the street and various interiors into a stage. Wurm thinks up curious poses or absurd contortions for the collaborators, he provides clear and simple directions, thus issuing the signal to translate the performative action back into static photographs. Attempts to lie on narrow surfaces, to stick one’s head into a wall, or to balance two cups on one’s feet in the air while lying supine, are not always successful. Of course, anyone who allows themselves to be drawn into this unusual artistic experiment must confront their own physical limitations as well as their boundaries of modesty.

For years, Barbara Probst has surprised viewers with her own playfully experimental blend of classical street photography, portraiture, still life and, more recently, fashion. She arranges her photographs into diptychs, triptychs, and occasionally into wall-sized tableaux consisting of a dozen individual images. They always bear the same title – Exposures – and are distinguished with an image number along with the location and date of the shoot. The date is indicated to the day and exact minute. She photographs the same situation with several cameras from different angles at the same time, triggered at exactly the same moment by radio waves. The simultaneous multiple perspectives captured by the cameras is then flattened, so to speak, once they are hung on the walls of the exhibition space.

Viviane Sassen also works mainly with the human body. She sometimes captures it in extreme contortions for her experimental fashion images. She choreographs and stages her model’s bodies in unexpected ways, for example by coloring their skin or depicting them obscured by shadow, mirrored, superimposed by objects, and often abstracted by cropping or framing the images. Occasionally she inverts the generally valid order of above and below, which results in a sense of disorientation for the viewer. Sassen challenges us as viewers and raises questions about common clichés. As a former model, she knows both sides, in front of and behind the camera. As she once stated in an interview, it is through her own photographic works that she has been able to reclaim power over her own body.

Since the 1990s, Inez & Vinoodh have been irritating the world of fashion since the 1990s with surreal images. Their techniques include digital image manipulation, which they use to fuse the bodies of men and women. Inez & Vinoodh not only push the boundaries of common modes of representation but also the limits of reality. At other times, they have radically altered or combined the sexes and skin colors of their protagonists. As such, their images embody the transgression of boundaries, and this connects them to Newton’s earlier strategy of questioning “good taste” and subtly but intentionally challenging it visually “from within the system.” They likewise shoot magazine editorials and work directly with a number of famous designers, and count among the most influential contemporary photographers with their iconic imagery.

We also encounter a sense of ambiguity in the work of Cindy Sherman. In her early, small-format black-and-white series Untitled Film Stills from the late-1970s, she slips into ever-new roles like an actress. Despite appearing to be unspectacular observations from everyday life, they are actually deliberately staged, with the artist as the main character. Sherman continued the idea of role playing in her work, later disguising herself behind thick layers of make-up and wigs, masks, or breast prostheses in her colorful, untitled self-portraits from the year 2000. Her games of transformation, camouflage, and representation naturally include many cinematic references – some portraits have the explicit feel of film stills, featuring an aging actress starring in a movie that has yet to be made.

Yang Fudong’s black-and-white photography is also inspired by the medium of film, specifically by film noir of the 1960s and even earlier films from Shanghai. Fudong seems to invoke a timeless past with his nude photographs tinged with melancholy; in his films, as well, we encounter narratives that are similarly imbued with a sense of mystery. Such an open show of nudity is still considered a provocation in large parts of Chinese society today. In Fudong’s New Women series, one or more nude women sit or stand in a sparsely but luxuriously equipped studio set. The female models – in both the static images and the film – are reminiscent of Brassaï’s portraits of prostitutes from Paris in the 1930s, which were an important source of inspiration for Newton’s later, ambivalent fashion photographs. The exhibition Body Performance thus closes the circle by means of myriad approaches across different cultures and times.

It was in the 1970s that Robert Longo shot his photo sequence Men in the Cities on the roof of a high-rise building in New York City, which he later reinterpreted as large-format charcoal drawings. In these images we see people caught by the camera in unnatural poses. They appear to be dancing wildly, or replaying scenes from American western, war, or gangster films – for example, when someone seems to fall in a hail of imaginary bullets. In fact, it was such a film still from Fassbinder’s The American Soldier from 1970 that inspired Longo to create this series of performative images. On the roof of his loft, his models dodged objects that were swinging around or thrown at them, while Longo photographed them falling to the ground or lying there contorted.

Robert Mapplethorpe, on the other hand, choreographed only one person in the image presented here: the former bodybuilding world champion, Lisa Lyon, who referred to herself as a sculptor of her own body. We see her lying nude on a boulder in Joshua Tree National Park in California, in 1980. The rock’s hard surface contrasts with her soft skin, while its massive strength corresponds to Lyons’s muscular legs. In this unconventional open-air setting, Mapplethorpe presents us with a ballet-like choreography. Everything can become a stage – an interplay between seeing and being seen. At around the same time, Newton worked with Lyon in California and Paris. With this “strong woman” in the truest sense of the word, another circle closes in the current exhibition Body Performance.

In this exhibition, we encounter role play and physical transformation as contemporary photographic perspectives on the most diverse visual aspects of the body and movement. As we view these images, questions come into focus concerning how we are perceived by others and by ourselves, identity, and the collective.

Matthias Harder