Medardo Rosso

Inventing Modern Sculpture

18 Oct 2024 - 23 Feb 2025

Photo: Markus Wörgötter

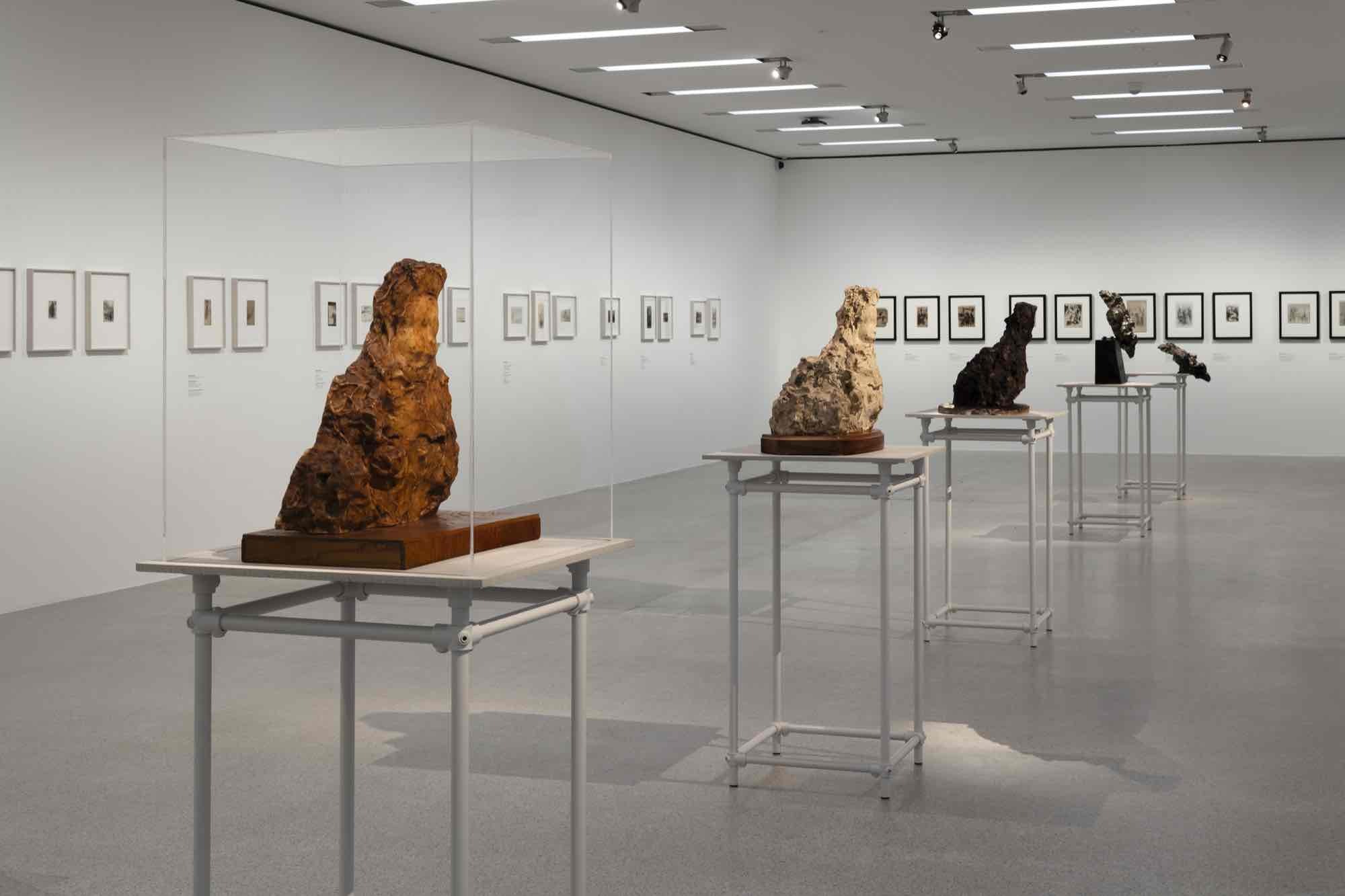

Louise Bourgeois, Child devoured by kisses, 1999, Private collection, Courtesy of Xavier Hufkens, Eugène Carrière, Elise riant, 1895, Galerie Jocelyn Wolff, Eugène Carrière, Le Sommeil (Jean-René Carrière), 1897, Galerie Jocelyn Wolff, Medardo Rosso, Aetas aurea, ca. 1886, Wax over plaster, Amedeo Porro Fine Arts Lugano/London

Photo: Markus Wörgötter

In the foreground: Edgar Degas, Little dancer aged fourteen, ca. 1922 (1878–1881), Sainsbury Centre, UEA, UK

Vis-à-vis: Medardo Rosso, Grande Rieuse, 1892 (1891–1892), Plaster, dark painted, Private collection, Medardo Rosso, Grande Rieuse, 1903–1904 (1891–1892), Wax over plaster, GAM – Galleria d’Arte Moderna di Milano, Medardo Rosso, Rieuse, 1894 (1890), Bronze, PCC, Pieter Coray Collection

Photo: Markus Wörgötter

Hans Josephsohn, Ohne Titel, 1997, Kesselhaus Josephsohn, St. Gallen, Rosemarie Trockel, O-Sculpture 2, 2012, Private collection / Sprüth Magers, Berlin, Medardo Rosso, Madame Noblet, after 1914 (1897), Plaster, Museo Medardo Rosso, Barzio

Medardo Rosso, Madame Noblet, 1897–1898 (1897), Bronze, GAM – Galleria D’Arte Moderna di Milano

Photo: Markus Wörgötter

While Rosso was indeed close to the Impressionist movement, he operated on the fringes and in the liminal areas in terms of method, media, and material—thus captivating the minds of many artists to this day. At the same time, his oeuvre is hard to grasp and, unlike Rodin’s, has remained virtually hidden from the broader public’s perception. Now, mumok presents a comprehensive retrospective of the artist with more than fifty sculptures and a large selection of photographs, photocollages, and drawings—while also building on the earliest holdings on the museum’s collection.

The exhibition follows the relational thinking of Medardo Rosso, who frequently exhibited his output in “conversation” with comparable works, and contextualizes his oeuvre with selected works by about fifty artists—among them Edgar Degas, Constantin Brâncuși, Louise Bourgeois, Jasper Johns, Robert Morris, Lynda Benglis, Eva Hesse, Marisa Merz, and Phyllida Barlow—who resonate directly or indirectly with Rosso. The show illustrates how Rosso’s work was a clarion call for crucial paradigm shifts in twentieth century art. From the monumental to the anti-monumental; from form to material; from originality and uniqueness to serial (self-)repetition and reprise; from the final, completed work to the ever-malleable, to the process and the event; from autonomy to spatial and contextual orientation; and ultimately to a resonance with the environment, the reciprocity of subject and object, seer and seen, touching and being touched.

Excepting a year of study at the Accademia di Brera in Milan, Medardo Rosso was self-taught. Born in Turin in 1858, he was a permanent resident of Paris from 1889 on, where he befriended Auguste Rodin and became his collaborator and later rival. Both artists sought to radically redefine the ostensibly unmodern medium of sculpture, which had been stuck in the confines of the monumental. Rosso tackled this by making the radical attempt to bring sculpture closer to life and to “animate” the medium. In their intimate scale, fragility and openness, his kinetic “blurry” sculptures not only overcome the typically male tradition of the heroic monument built for eternity. It is also because Rosso saw himself as a category-defying citizen of the world “born on a train”—in opposition to the burgeoning nationalism of his time— that he avoided portraying glorious heroic tales in favor of depicting ordinary people going about their day, visibly subject to time. Rosso’s “blurry” sculptures not only reflect the radical changes in perception of his time but also deal with the social upheavals around 1900, in a society marked by tremendous processes of modernization and alienation.

For his sculptures, Rosso often reverted to bronze, which he cast himself using the age-old method of lost-wax casting. He also employed wax and plaster, so-called “poor” materials that had hitherto been deemed unworthy of art and used in the sculptural preproduction process only but were more permeable, malleable, and organic than common stone. Rosso also devised strategies to shift the focus to the material and the creative process. He developed essential media- and materialaesthetic considerations on sculpture and the relationship between the figure and its environment through the medium of photography, which he systematically included in his creative process from 1900 on and exhibited together with his sculptures as ensembles. He repeatedly made a show of casting figures in his studio, thus emphasizing—unlike most of his contemporaries—his dual role of artist and artisan.

Rosso was only to work on about forty subjects in total. In lieu of a final piece we are presented the repetitive loop of a potentially incompletable return to a moment once begun and continually revived anew. He used the reproduction technologies of casting and photography, while avoiding the familiar hierarchies of original and copy, of production and reproduction, calling into question the fledgling commercial art market and its logics of exploitation. At the same time, Rosso wanted to use his methodology to enter a dialog with the world around him, which he perceived as being in a state of constant flux, and to keep encountering it in fresh, new ways. Especially in a time when rethinking the relationship between material bodies and their increasingly technologically networked environment is becoming ever more pressing, Rosso’s work appears “alarmingly alive”—to borrow the words of sculptor Phyllida Barlow.

Medardo Rosso’s busy exhibition activities took him all over Europe. His first appearance in Austria was in 1903 as part of the Impressionism exhibition at the Vienna Secession. In 1905, Kunstsalon Artaria at Kohlmarkt presented his first comprehensive solo show. Rosso’s exhibition practice, with which he directed his audience’s perception, attracted a lot of attention at the time. In a newspaper review, art critic Ludwig Hevesi wrote that Rosso presented his objects in iron-framed glass cases that he had made himself and that he strategically positioned employing electric lighting. For this purpose, he insisted that the exhibition architecture remained scant—an unusual design element at the time. Another thing specific to Rosso’s exhibition practice was the incorporation of works by contemporaries like Rodin and copies of works from other periods of art history.

One hundred and twenty years after his last presentation in Vienna, mumok is now taking Rosso’s principle of comparative viewing as a starting point to show his work in the spirit of an expanded retrospective in the larger context of the artistic developments of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. In select juxtapositions with more than eighty works by artists from a variety of international collections, Rosso’s experimental approach emerges as one that has continued to shape the artistic landscape.

Artists in dialog with Medardo Rosso: Giovanni Anselmo / Guillaume Apollinaire / Francis Bacon / Nairy Baghramian / Olga Balema / Phyllida Barlow / Lynda Benglis / Louise Bourgeois / Anton Giulio Bragaglia / Constantin Brâncuși / Eugène Carrière / John Chamberlain / Honoré Daumier / Edgar Degas / Raymond Duchamp-Villon / Luciano Fabro / Loïe Fuller / Isa Genzken / Alberto Giacometti / Robert Gober / David Hammons / Eva Hesse / Jasper Johns / Hans Josephsohn / Ellsworth Kelly / Käthe Kollwitz / Yayoi Kusama / Maria Lassnig / Sherrie Levine / Matthijs Maris / Marisa Merz / Amedeo Modigliani / Robert Morris / Juan Muñoz / Senga Nengudi / Carol Rama / Auguste Rodin / Richard Serra / Edward Steichen / Georges Seurat / Erin Shirreff / Alina Szapocznikow / Paul Thek / Rosemarie Trockel / Hannah Villiger / Andy Warhol / Rebecca Warren / James Welling / Francesca Woodman

Curated by Heike Eipeldauer