Jean Dubuffet

The Last Two Years

20 Jan - 10 Mar 2012

Jean Dubuffet

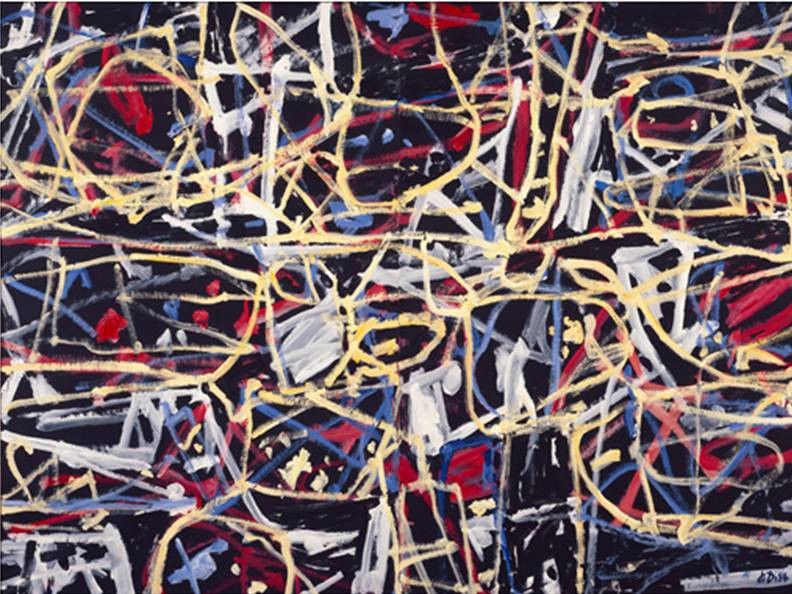

Fluence, November 19, 1984

acrylic on canvas-backed paper

39-1/2" x 52-3/4" (100.3 cm x 134 cm)

Private collection

Fluence, November 19, 1984

acrylic on canvas-backed paper

39-1/2" x 52-3/4" (100.3 cm x 134 cm)

Private collection

JEAN DUBUFFET

The Last Two Years

20 January - 10 March, 2012

The Pace Gallery is pleased to present Jean Dubuffet: The Last Two Years, on view at 510 West 25th Street from January 20 through March 10, 2012. An opening will be held on Thursday, January 19 from 6 to 8 p.m. The exhibition will be accompanied by a catalogue with an essay by curator Harmony Murphy.

During the final two years of Jean Dubuffet’s life, his canvases exploded with raw emotion. The artist’s mental landscapes described a non-place, made perceptible by fluid intertwining lines and radiant colors that seem drawn from an alternate reality. “To see the last works,” Murphy writes, “is to see all of Dubuffet, his theories contracted into an energetic force comprised of wild, fluid brushstrokes that appear as if they could escape from the confines of any boundaries imposed upon them.” After twelve years of working on his Hourloupe cycle (the longest series of his career) with a palette of primarily red, blue, and black, contained by thick black outlines, in 1983 Dubuffet unleashed an extended color palette across the canvas, removing the borders and a representational reference point. Nearly twenty works drawn from the final two bodies of work by the artist (Mires and Non-Lieux) will be on view.

From February 1983 to February 1984, Dubuffet painted the Mires series exclusively. These paintings were, as Murphy explains, “the alarm clock that wakes us from dreaming in the language of the Hourloupes,” so that “we are, again, reset.” The “Test Patterns,” as the artist referred to the paintings, were to evoke in viewers a visceral reaction that might rid the mind of the teachings of culture and tradition so as to see them with a naked eye. The Kowloons—a title which references the city in Hong Kong that Dubuffet imagined but never travelled to—are vibrant paintings of blue and red on bright yellow ground. The Boléros, limited to a palette of blue, red, and white, vibrate with the energy of the Spanish and Cuban dance they describe.

Dubuffet’s final series, painted in 1984, were entitled Non-Lieux, a legal term meaning neither guilty nor innocent—in effect, “no verdict.” In a letter to Arne Glimcher towards the end of his life, Dubuffet explained his conception for the paintings:

These paintings were intended to challenge the objective nature of being (être). The notion of being is presented here as relative rather than irrefutable: it is merely a projection of our minds, a whim of our thinking. The mind has the right to establish being wherever it cares to and for as long as it likes. There is no intrinsic difference between being and fantasy (fantasme); being is an attribute that the mind assigns to fantasy. One could apply the term ‘nihilism’ to this challenge of being, but it is reverse nihilism, since it confers the power of being on any fantasy whatsoever, given that being is a secretion of our minds.

These paintings are an exercise for training the mind to deal with a being that it creates for itself rather than one imposed upon it. The mind should get rid of the feeling that it alone must change while being cannot change; the mind will train itself to vary being rather than varying itself, the mind will train itself to move through a space in which being is variable and never anything but a hypothesis, the mind will practice using its ability to provide its own fulcrums wherever it wishes, it will learn to rely on illusion, to create the ground on which it walks. The mind will learn how to move through all the various degrees of being, and it will feel at ease when being is undependable, flicks on and off, remains potential, and sleeps or wakes at will. Being and thinking are one and the same.

Jean Dubuffet (1901–1985) was one of the most enigmatic painters of the twentieth century. A student of the Académie Julian in Paris, he left school in 1918 to pursue an independent form of art education. Like many of his generation in Europe in the wake of World War II, Dubuffet sought artistic authenticity outside of tradition, in the margins of society. He looked to the art of prisoners, psychics, the uneducated, and the insane to liberate his own creativity and coined the term “Art Brut,” a predecessor to outsider art of the late 1940s.

In his lifetime, Jean Dubuffet was the subject of twelve major museum retrospectives including The Museum of Modern Art (1962), which traveled to The Art Institute of Chicago and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Tate Gallery, London (1966); Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam (1966); Museum of Fine Arts, Dallas (1966), which traveled to the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; Musée des Beaux-Arts, Montreal (1969-70); and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (1973, 1981). Today, Jean Dubuffet’s work can be found in more than fifty public collections worldwide.

In 1973, Dubuffet established a foundation to preserve and realize his monumental works. The foundation is located in Paris and in Périgny-sur-Yerres, where the Closerie Falbala, a monumental sculpture and the artist’s major work (designated a historic monument in 1998), is situated near the former sculpture studios that house the artist’s architectural models. The Villa Falbala, which Dubuffet built to shelter his Cabinet Logologique, stands at the center of this enormous walled simulacrum of a garden. Paintings and elements from the artist’s production of Coucou Bazar, performed in 1973 at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, are also on view in Périgny-sur-Yerres.

The Pace Gallery has represented Jean Dubuffet since 1968 and since that time fifteen solo exhibitions of his work have been mounted at the gallery.

The Last Two Years

20 January - 10 March, 2012

The Pace Gallery is pleased to present Jean Dubuffet: The Last Two Years, on view at 510 West 25th Street from January 20 through March 10, 2012. An opening will be held on Thursday, January 19 from 6 to 8 p.m. The exhibition will be accompanied by a catalogue with an essay by curator Harmony Murphy.

During the final two years of Jean Dubuffet’s life, his canvases exploded with raw emotion. The artist’s mental landscapes described a non-place, made perceptible by fluid intertwining lines and radiant colors that seem drawn from an alternate reality. “To see the last works,” Murphy writes, “is to see all of Dubuffet, his theories contracted into an energetic force comprised of wild, fluid brushstrokes that appear as if they could escape from the confines of any boundaries imposed upon them.” After twelve years of working on his Hourloupe cycle (the longest series of his career) with a palette of primarily red, blue, and black, contained by thick black outlines, in 1983 Dubuffet unleashed an extended color palette across the canvas, removing the borders and a representational reference point. Nearly twenty works drawn from the final two bodies of work by the artist (Mires and Non-Lieux) will be on view.

From February 1983 to February 1984, Dubuffet painted the Mires series exclusively. These paintings were, as Murphy explains, “the alarm clock that wakes us from dreaming in the language of the Hourloupes,” so that “we are, again, reset.” The “Test Patterns,” as the artist referred to the paintings, were to evoke in viewers a visceral reaction that might rid the mind of the teachings of culture and tradition so as to see them with a naked eye. The Kowloons—a title which references the city in Hong Kong that Dubuffet imagined but never travelled to—are vibrant paintings of blue and red on bright yellow ground. The Boléros, limited to a palette of blue, red, and white, vibrate with the energy of the Spanish and Cuban dance they describe.

Dubuffet’s final series, painted in 1984, were entitled Non-Lieux, a legal term meaning neither guilty nor innocent—in effect, “no verdict.” In a letter to Arne Glimcher towards the end of his life, Dubuffet explained his conception for the paintings:

These paintings were intended to challenge the objective nature of being (être). The notion of being is presented here as relative rather than irrefutable: it is merely a projection of our minds, a whim of our thinking. The mind has the right to establish being wherever it cares to and for as long as it likes. There is no intrinsic difference between being and fantasy (fantasme); being is an attribute that the mind assigns to fantasy. One could apply the term ‘nihilism’ to this challenge of being, but it is reverse nihilism, since it confers the power of being on any fantasy whatsoever, given that being is a secretion of our minds.

These paintings are an exercise for training the mind to deal with a being that it creates for itself rather than one imposed upon it. The mind should get rid of the feeling that it alone must change while being cannot change; the mind will train itself to vary being rather than varying itself, the mind will train itself to move through a space in which being is variable and never anything but a hypothesis, the mind will practice using its ability to provide its own fulcrums wherever it wishes, it will learn to rely on illusion, to create the ground on which it walks. The mind will learn how to move through all the various degrees of being, and it will feel at ease when being is undependable, flicks on and off, remains potential, and sleeps or wakes at will. Being and thinking are one and the same.

Jean Dubuffet (1901–1985) was one of the most enigmatic painters of the twentieth century. A student of the Académie Julian in Paris, he left school in 1918 to pursue an independent form of art education. Like many of his generation in Europe in the wake of World War II, Dubuffet sought artistic authenticity outside of tradition, in the margins of society. He looked to the art of prisoners, psychics, the uneducated, and the insane to liberate his own creativity and coined the term “Art Brut,” a predecessor to outsider art of the late 1940s.

In his lifetime, Jean Dubuffet was the subject of twelve major museum retrospectives including The Museum of Modern Art (1962), which traveled to The Art Institute of Chicago and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Tate Gallery, London (1966); Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam (1966); Museum of Fine Arts, Dallas (1966), which traveled to the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; Musée des Beaux-Arts, Montreal (1969-70); and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (1973, 1981). Today, Jean Dubuffet’s work can be found in more than fifty public collections worldwide.

In 1973, Dubuffet established a foundation to preserve and realize his monumental works. The foundation is located in Paris and in Périgny-sur-Yerres, where the Closerie Falbala, a monumental sculpture and the artist’s major work (designated a historic monument in 1998), is situated near the former sculpture studios that house the artist’s architectural models. The Villa Falbala, which Dubuffet built to shelter his Cabinet Logologique, stands at the center of this enormous walled simulacrum of a garden. Paintings and elements from the artist’s production of Coucou Bazar, performed in 1973 at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, are also on view in Périgny-sur-Yerres.

The Pace Gallery has represented Jean Dubuffet since 1968 and since that time fifteen solo exhibitions of his work have been mounted at the gallery.