Photography as a weapon of class

07 Nov 2018 - 04 Feb 2019

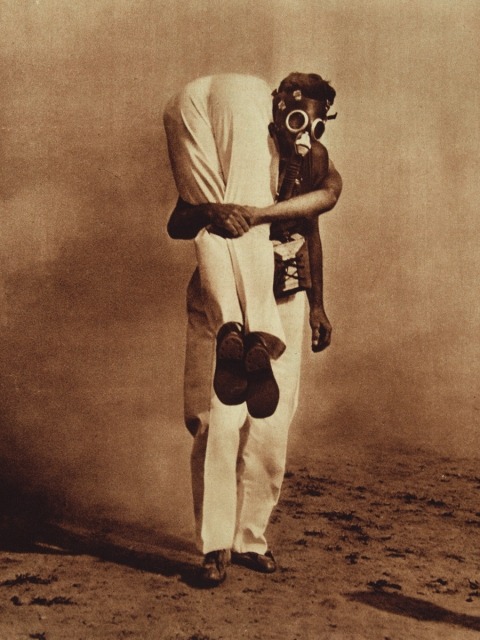

Illustration pour Paul Vaillant-Couturier, « La Prochaine, communiste ! », supplément à « L’ Humanité », 1ère année, n°2, 1er août 1932, p.20 (conception graphique du numéro : Max Morise, Pontabry et Tchimoukow)

PHOTOGRAPHY AS A WEAPON OF CLASS

7 November 2018 - 4 February 2019

“Photography as a weapon of class” are the words with which the journalist Henri Tracol (1909–1997) begins his manifesto on unifying the photography section of the association of revolutionary writers and artists (AEAR). The association was founded in Paris in 1932, against a background of growing political, economic and social upheaval, and brought together, alongside other sectors of the artistic and cultural domain (theatre, music, cinema, literature, painting, etc.) some of the most committed photographers of the Paris avant-garde: Jacques-André Boiffard, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Chim, André Kertész, Germaine Krull, Eli Lotar, Willy Ronis, René Zuber, and many more besides. Alongside the laypeople and workers whom they followed for their work, these photographers experimented with a language that was at the intersection of critical discourse, the militant gesture and the documentary aesthetic. They drew on Soviet and German examples while managing to carve their own path through the French social and political context.

This exhibition, compiled from the photographic collection of the Musée National d’Art Moderne, is the result of a close scientific collaboration lasting almost three years and involving the young researchers of Labex Arts-H2H and the museum’s own photography studio. As a result of their work, the aim of which was to identify and contextualise the social photographs in the Christian Bouqueret collection (comprising some 7,000 shots) acquired in 2011, a gap has been filled in the history of photography in France between the wars. The project therefore sets to one side the repertoire of the Popular Front and the icons of the Spanish Civil War, which, even today, form most people’s ideas of what the situation was like at the time. The period that preceded these two seminal moments of that decade is a veritable hothouse, from a social and activity point of view, and its history remains to be written.

Built around two themes and a number of formal series, and featuring a selection of around thirty unique documents and a hundred or so works by the biggest names in modern photography, the exhibition examines the shift from a photogenic iconography of poverty to social consciousness: from the Paris of Eugène Atget to the keen eye of the Russian writer Ilya Ehrenburg, who was both shocked and awed by the den of destitution that was the capital in the early 1930s. Specific techniques, such as photomontage, are given particular prominence, with the architect and militant Charlotte Perriand, who embraced the “explosive” potential of photographic montage. Finally, recurring iconographic subjects, from the image of the worker to representations of the collective struggle, and not forgetting the antics of the illustrated left-wing press (Regards, Vu), serve to complete, with the help of recent discoveries, the missing parts of the picture of documentary and social photography during the two World Wars.

7 November 2018 - 4 February 2019

“Photography as a weapon of class” are the words with which the journalist Henri Tracol (1909–1997) begins his manifesto on unifying the photography section of the association of revolutionary writers and artists (AEAR). The association was founded in Paris in 1932, against a background of growing political, economic and social upheaval, and brought together, alongside other sectors of the artistic and cultural domain (theatre, music, cinema, literature, painting, etc.) some of the most committed photographers of the Paris avant-garde: Jacques-André Boiffard, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Chim, André Kertész, Germaine Krull, Eli Lotar, Willy Ronis, René Zuber, and many more besides. Alongside the laypeople and workers whom they followed for their work, these photographers experimented with a language that was at the intersection of critical discourse, the militant gesture and the documentary aesthetic. They drew on Soviet and German examples while managing to carve their own path through the French social and political context.

This exhibition, compiled from the photographic collection of the Musée National d’Art Moderne, is the result of a close scientific collaboration lasting almost three years and involving the young researchers of Labex Arts-H2H and the museum’s own photography studio. As a result of their work, the aim of which was to identify and contextualise the social photographs in the Christian Bouqueret collection (comprising some 7,000 shots) acquired in 2011, a gap has been filled in the history of photography in France between the wars. The project therefore sets to one side the repertoire of the Popular Front and the icons of the Spanish Civil War, which, even today, form most people’s ideas of what the situation was like at the time. The period that preceded these two seminal moments of that decade is a veritable hothouse, from a social and activity point of view, and its history remains to be written.

Built around two themes and a number of formal series, and featuring a selection of around thirty unique documents and a hundred or so works by the biggest names in modern photography, the exhibition examines the shift from a photogenic iconography of poverty to social consciousness: from the Paris of Eugène Atget to the keen eye of the Russian writer Ilya Ehrenburg, who was both shocked and awed by the den of destitution that was the capital in the early 1930s. Specific techniques, such as photomontage, are given particular prominence, with the architect and militant Charlotte Perriand, who embraced the “explosive” potential of photographic montage. Finally, recurring iconographic subjects, from the image of the worker to representations of the collective struggle, and not forgetting the antics of the illustrated left-wing press (Regards, Vu), serve to complete, with the help of recent discoveries, the missing parts of the picture of documentary and social photography during the two World Wars.