Robert Delaunay

15 Oct 2014 - 12 Jan 2015

Robert Delaunay

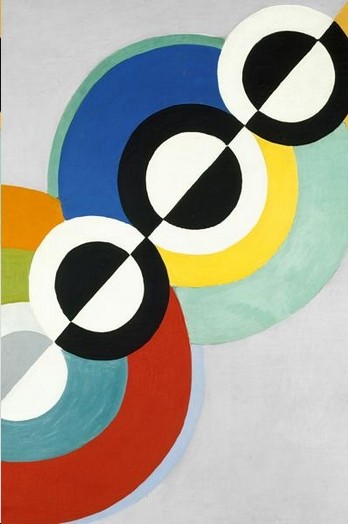

Rythmes, 1934

© photo: Jacqueline Hyde / Centre Pompidou, mnam/cci, dist. RMN-GP, © Domaine public

Rythmes, 1934

© photo: Jacqueline Hyde / Centre Pompidou, mnam/cci, dist. RMN-GP, © Domaine public

ROBERT DELAUNAY

Endless rythms

15 October 2014 - 12 January 2015

Curator : Mnam-Cci, Angela Lampe

"Rythmes sans fin" explores the astonishing work of Robert Delaunay during the Twenties and Thirties.

The exhibition "Rythmes sans fin" devoted by the Centre Pompidou to the extraordinarily rich and varied Robert Delaunay collection brings together around 80 works in the form of paintings, drawings, reliefs, mosaics, models, a tapestry and a large number of documentary photographs. Thanks to the large donation made by Sonia Delaunay and her son Charles to the Musée National d’Art Moderne in 1964, the Centre Pompidou now possesses the world's largest collection of works by Robert and Sonia Delaunay. "Rythmes sans fin" explores the astonishing body of work that Robert Delaunay began after the war. Particularly after the Thirties, he regained an interest in mural painting, and thus extended his field of work to the modern environment by moving towards monumentality. The exhibition reveals how his painting gradually moved away from the flat plane of the painting into the architectural space.

The second part of the exhibition is devoted to the spectacular interior design projects that Delaunay (together with the architect Félix Aublet) created for the Palais des Chemins de Fer and the Palais de l’Air, and which caused a sensation at the International Exhibition of 1937.

The selection also contains advertising projects from the Delaunay collection in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, and architectural plans now in the Archives Nationales.

While Baudelaire defined modernity by temporality – the transitory versus the unchanging –, Delaunay saw it in terms of the outsize. Observing new features in the urban landscape such as the gigantism of the Eiffel Tower and the impact of advertising panels, together with the electrification of street lighting and the rapid rise of aviation, he perceived this modernity as visual excess, an optical sensation that submerged the viewer – something monumental, dazzling and of searing intensity. How could the profusion of unusual viewpoints, the increased mobility and the incessant stimulation of our optic nerves – all those simultaneous shocks that pepper modern urban life – be transposed into forms and colours? His quest for "pure painting", which puts the viewer's eye in direct contact with turbulent reality, was mingled with a challenge to the very medium of easel painting. From the first Paysage au disque of 1906, on the other side of his Self-portrait, to the first circular forms he painted in 1913, Delaunay, inspired by astral theories, the movement of propellers and the halos of electric lamps, sought to move past the limits imposed by the format of the canvas by incorporating a gyratory dynamic into his compositions. With each new form of pictorial research, which led to his "first non-objective painting" with his first disc of 1913, the act of seeing established itself as the subject of his painting. Because it acted directly on the viewer's sensibility, this painting took on a "popular aspect" for Delaunay. His desire to abandon the easel and move out of the studio can also be understood: should we not see simultaneous painting everywhere, in the street, in stores, in the theatre, in the cinema, in apartments and on buildings?

A quest for "pure painting" that puts the viewer's eye in direct contact with turbulent reality.

After some initial experiments with the film director Abel Gance in 1913, and various projects devised with the Ballets Russes in Spain during 1918, Delaunay began to take more of an interest in the applied arts in Paris, where he and Sonia went to live in 1921. He started to design advertising posters, creating around 30 studies up until 1924. None of these projects ever came to anything. Ranging from the promotion of aperitif and car brands to public events, these projects enabled him to combine his circular forms, propellers and discs with the urban environment. The importance that Delaunay, like Fernand Léger, gave to street displays (such as posters in shop windows) reflected the new ambition then inspiring artists: the visual reorganisation of the contemporary world. Painters, disillusioned with their solitary, solipsistic kind of work, sought to participate actively in shaping urban modernity. Here, they thought the best means of doing so was by integrating art into architecture. So it is unsurprising that in 1925, the architect Robert Mallet-Stevens called on both Delaunay and Léger to decorate the hall of an imaginary French embassy presented at the Exhibition of Decorative Arts. In a huge, well-lit open space, Delaunay installed a new narrow, vertical version of La Ville de Paris: a large and ambitious painting intended for the Salon des Indépendants of 1912. His participation meant that he could integrate his painting into a contemporary architectural environment for the first time, and try out the impact of his compositions on a monumental scale. He repeated the experience the following year, collaborating with the stage director René Le Somptier on the film Le P’tit Parigot. Delaunay chose several of his recent paintings, in imposing formats, to ornament the walls of the modernist apartment where the film was shot. These included the third version of Manège de cochons, dating from 1922.

A new ambition was then inspiring artists: the visual reorganisation of the contemporary world.

1930 marked a turning point. Robert Delaunay finally abandoned figurative painting – in particular the portraits of his friends that he had been producing (mainly for financial reasons) since his return to France. He returned to his pre-war circular forms, eradicating every figurative reference from them. His brightly-coloured painting Rythmes, Joie de vivre marks the transition towards the series Rythmes sans fin and Rythmes, still more radical pictorially, and emblematic of the works of his final years. The contrast between white and black structures the twisting movement that enlivens the surfaces. According to the artist, these works could "combine intimately with architecture, while being architectonically constructed in themselves." Instead of intervening on the surface, they respect the plane of the wall and take up the spatial layout, as though prolonging the experience of walking around.

The Rythmes sans fin project rapidly moved beyond the medium of painting. In a letter to his friend Albert Gleizes, Delaunay said he was working "at full stretch" to develop new materials in every aspect of his work. In 1935, he exhibited wall-coverings in reliefs and colours that were totally new in technical terms, and were produced using an extraordinary variety of materials. The surfaces came alive through the play on textures, and the contrast between smooth and rough, or shiny and matt. Delaunay was aiming for nothing less than a revolution in the arts, no longer in the pictorial field, but in the realm of architecture. "I am creating a revolution in the walls," he said in 1935. This research on coverings was only one step towards the realisation of a major architectural project. The opportunity came with the layout of two pavilions dedicated to modern transport at the International Exhibition entitled "Arts and techniques of modern life", held in Paris in 1937. The exemption of a new coloured translucent material, Rhodoid, enabled Delaunay to eliminate the materiality of buildings in combination with projected light. The interior of the Palais de l’Air dissolved into a purely atmospheric polychrome display, as though Delaunay were seeking to stage the profusion of sensations of which he had never grown weary – the very sensations we draw from modern life.

"Painting that creates a building style: the very definition of the characteristics of art and its relevance to modern life." Robert Delaunay, 1939-1940

Endless rythms

15 October 2014 - 12 January 2015

Curator : Mnam-Cci, Angela Lampe

"Rythmes sans fin" explores the astonishing work of Robert Delaunay during the Twenties and Thirties.

The exhibition "Rythmes sans fin" devoted by the Centre Pompidou to the extraordinarily rich and varied Robert Delaunay collection brings together around 80 works in the form of paintings, drawings, reliefs, mosaics, models, a tapestry and a large number of documentary photographs. Thanks to the large donation made by Sonia Delaunay and her son Charles to the Musée National d’Art Moderne in 1964, the Centre Pompidou now possesses the world's largest collection of works by Robert and Sonia Delaunay. "Rythmes sans fin" explores the astonishing body of work that Robert Delaunay began after the war. Particularly after the Thirties, he regained an interest in mural painting, and thus extended his field of work to the modern environment by moving towards monumentality. The exhibition reveals how his painting gradually moved away from the flat plane of the painting into the architectural space.

The second part of the exhibition is devoted to the spectacular interior design projects that Delaunay (together with the architect Félix Aublet) created for the Palais des Chemins de Fer and the Palais de l’Air, and which caused a sensation at the International Exhibition of 1937.

The selection also contains advertising projects from the Delaunay collection in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, and architectural plans now in the Archives Nationales.

While Baudelaire defined modernity by temporality – the transitory versus the unchanging –, Delaunay saw it in terms of the outsize. Observing new features in the urban landscape such as the gigantism of the Eiffel Tower and the impact of advertising panels, together with the electrification of street lighting and the rapid rise of aviation, he perceived this modernity as visual excess, an optical sensation that submerged the viewer – something monumental, dazzling and of searing intensity. How could the profusion of unusual viewpoints, the increased mobility and the incessant stimulation of our optic nerves – all those simultaneous shocks that pepper modern urban life – be transposed into forms and colours? His quest for "pure painting", which puts the viewer's eye in direct contact with turbulent reality, was mingled with a challenge to the very medium of easel painting. From the first Paysage au disque of 1906, on the other side of his Self-portrait, to the first circular forms he painted in 1913, Delaunay, inspired by astral theories, the movement of propellers and the halos of electric lamps, sought to move past the limits imposed by the format of the canvas by incorporating a gyratory dynamic into his compositions. With each new form of pictorial research, which led to his "first non-objective painting" with his first disc of 1913, the act of seeing established itself as the subject of his painting. Because it acted directly on the viewer's sensibility, this painting took on a "popular aspect" for Delaunay. His desire to abandon the easel and move out of the studio can also be understood: should we not see simultaneous painting everywhere, in the street, in stores, in the theatre, in the cinema, in apartments and on buildings?

A quest for "pure painting" that puts the viewer's eye in direct contact with turbulent reality.

After some initial experiments with the film director Abel Gance in 1913, and various projects devised with the Ballets Russes in Spain during 1918, Delaunay began to take more of an interest in the applied arts in Paris, where he and Sonia went to live in 1921. He started to design advertising posters, creating around 30 studies up until 1924. None of these projects ever came to anything. Ranging from the promotion of aperitif and car brands to public events, these projects enabled him to combine his circular forms, propellers and discs with the urban environment. The importance that Delaunay, like Fernand Léger, gave to street displays (such as posters in shop windows) reflected the new ambition then inspiring artists: the visual reorganisation of the contemporary world. Painters, disillusioned with their solitary, solipsistic kind of work, sought to participate actively in shaping urban modernity. Here, they thought the best means of doing so was by integrating art into architecture. So it is unsurprising that in 1925, the architect Robert Mallet-Stevens called on both Delaunay and Léger to decorate the hall of an imaginary French embassy presented at the Exhibition of Decorative Arts. In a huge, well-lit open space, Delaunay installed a new narrow, vertical version of La Ville de Paris: a large and ambitious painting intended for the Salon des Indépendants of 1912. His participation meant that he could integrate his painting into a contemporary architectural environment for the first time, and try out the impact of his compositions on a monumental scale. He repeated the experience the following year, collaborating with the stage director René Le Somptier on the film Le P’tit Parigot. Delaunay chose several of his recent paintings, in imposing formats, to ornament the walls of the modernist apartment where the film was shot. These included the third version of Manège de cochons, dating from 1922.

A new ambition was then inspiring artists: the visual reorganisation of the contemporary world.

1930 marked a turning point. Robert Delaunay finally abandoned figurative painting – in particular the portraits of his friends that he had been producing (mainly for financial reasons) since his return to France. He returned to his pre-war circular forms, eradicating every figurative reference from them. His brightly-coloured painting Rythmes, Joie de vivre marks the transition towards the series Rythmes sans fin and Rythmes, still more radical pictorially, and emblematic of the works of his final years. The contrast between white and black structures the twisting movement that enlivens the surfaces. According to the artist, these works could "combine intimately with architecture, while being architectonically constructed in themselves." Instead of intervening on the surface, they respect the plane of the wall and take up the spatial layout, as though prolonging the experience of walking around.

The Rythmes sans fin project rapidly moved beyond the medium of painting. In a letter to his friend Albert Gleizes, Delaunay said he was working "at full stretch" to develop new materials in every aspect of his work. In 1935, he exhibited wall-coverings in reliefs and colours that were totally new in technical terms, and were produced using an extraordinary variety of materials. The surfaces came alive through the play on textures, and the contrast between smooth and rough, or shiny and matt. Delaunay was aiming for nothing less than a revolution in the arts, no longer in the pictorial field, but in the realm of architecture. "I am creating a revolution in the walls," he said in 1935. This research on coverings was only one step towards the realisation of a major architectural project. The opportunity came with the layout of two pavilions dedicated to modern transport at the International Exhibition entitled "Arts and techniques of modern life", held in Paris in 1937. The exemption of a new coloured translucent material, Rhodoid, enabled Delaunay to eliminate the materiality of buildings in combination with projected light. The interior of the Palais de l’Air dissolved into a purely atmospheric polychrome display, as though Delaunay were seeking to stage the profusion of sensations of which he had never grown weary – the very sensations we draw from modern life.

"Painting that creates a building style: the very definition of the characteristics of art and its relevance to modern life." Robert Delaunay, 1939-1940