Beatriz Santiago Muñoz

Elogio al disparate

06 Dec 2024 - 23 Feb 2025

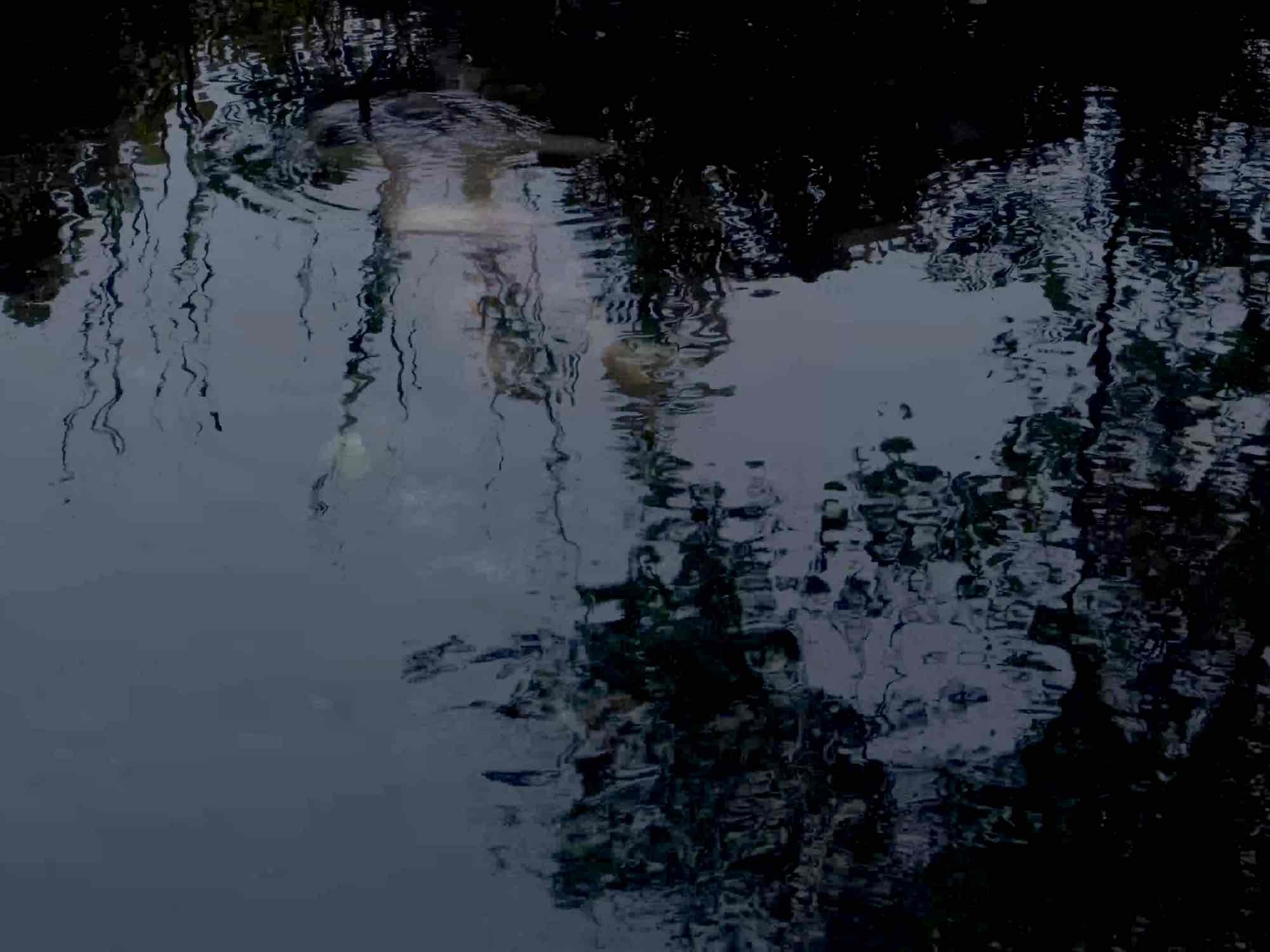

Beatriz Santiago Muñoz, Elogio al disparate (still), 2024, 16 mm transferred to digital video, Courtesy of the artist

“I love the un-film, the almost film, the broken film, the overly long film, the film with visible cracks, the film that reveals its guts. I’m into surprising formal choices for their poetic potential and, especially, I’m into films that upend what is taken for granted, whether it’s plot or continuity or even sense.” (Beatriz Santiago Muñoz, Frieze, no. 199, 2018)

Beatriz Santiago Muñoz is a firm believer in the transformative potential of the camera to re-imagine and re-signify the world. At the center of her three films shown at the Secession is, of all things, nonsense. The newly produced works that were shot on 16 mm stock and then transferred to video use free association and formal play to build relationships between sound and image that are not to be grasped by “making” rational sense.

The three films are inspired by jitanjáforas, invented nonsense words, and their exuberant use in Caribbean poetry and music in the twentieth century. These speculative words mostly unfold their poetic dimensions in their phonetic properties. They favor chaos, dissonance and revolutionary spirit over reactionary concepts of fixed truths that secure the political and societal status quo.

Muñoz’s films, too, invent “new words” and use formal methods such as attention to rhythm, shape, sound and movement while interrupting linear story-telling and the traditional production of meaning. The title of the work, Elogio al disparate (In Praise of Nonsense) refers to a short essay by the Peruvian Marxist José Carlos Mariátegui (1894–1930) on the poems of his compatriot, the writer Martín Adán (1908–1985). Mariátegui honors the power of nonsense as a denunciation of a fraudulent spirit and the philosophy of the old order and writes that it is this disorder that can speed its dissolution.

Muñoz’s practice mostly revolves around her native Puerto Rico, with references to Haitian poetics and feminist speculative fictions. Considered the world’s oldest colony, the island was under Spanish rule for over four centuries, followed by the U.S.’s invasion during the Spanish-American War in 1898. Whereas Puerto Rico is primarily known through exoticized portrayals, Muñoz tackles its political and ecological crises involving gentrification and displacement as well as its post-military spaces. Aiming to formulate alternative narratives, the artist often works with non-actors from local communities including activists or healers, whom she invites to reenact events from their own popular culture, history, and Indigenous mythology.

Muñoz’s works are rooted in long-term observation, a common practice in ethnography and documentary filmmaking. At the same time, the artist uses film not as a means of classical realism, but as a genre of poetry. That is why she embraces the vocabulary of theater and expanded cinema, consciously blurring the boundaries between fact and fiction. Inviting improvisation and chance, she explores the potential for re-writing history.

The confusing yet vivid state that emerges when the existing is disordered but new meaning hasn’t developed yet may feel uncomfortable in its arbitrariness—there is nothing solid, no logic or reason to hold on to in Muñoz’s new films—but it is also full of alternative readings, invention, play and possibilities. Or as the artist puts it: “I try to push forward at least a little bit the dissolution of an order that, too reliant on reason, might be blocking the view.”

The publication accompanying the exhibition Elogio al disparate documents an email conversation between the artist and Puerto Rican writer Claudia Becerra. In this dialogue, they exchange thoughts on the concept of nonsense and jitanjáforas, allowing themselves to drift in a spirit of free association while resisting the urge to impose form or meaning on everything. At the center of this exchange are excerpts and poems by Latin American authors such as Clarice Lispector, Alfonso Reyes, Alejandra Pizarnik, Mariano Brull, Francisco Matos Paoli, César Vallejo, José Carlos Mariátegui, Martín Adán, and Bobby Capó. Their texts are presented as a removable book within the book, shaping the artistic intervention.

Curated by Bettina Spörr

Beatriz Santiago Muñoz is a firm believer in the transformative potential of the camera to re-imagine and re-signify the world. At the center of her three films shown at the Secession is, of all things, nonsense. The newly produced works that were shot on 16 mm stock and then transferred to video use free association and formal play to build relationships between sound and image that are not to be grasped by “making” rational sense.

The three films are inspired by jitanjáforas, invented nonsense words, and their exuberant use in Caribbean poetry and music in the twentieth century. These speculative words mostly unfold their poetic dimensions in their phonetic properties. They favor chaos, dissonance and revolutionary spirit over reactionary concepts of fixed truths that secure the political and societal status quo.

Muñoz’s films, too, invent “new words” and use formal methods such as attention to rhythm, shape, sound and movement while interrupting linear story-telling and the traditional production of meaning. The title of the work, Elogio al disparate (In Praise of Nonsense) refers to a short essay by the Peruvian Marxist José Carlos Mariátegui (1894–1930) on the poems of his compatriot, the writer Martín Adán (1908–1985). Mariátegui honors the power of nonsense as a denunciation of a fraudulent spirit and the philosophy of the old order and writes that it is this disorder that can speed its dissolution.

Muñoz’s practice mostly revolves around her native Puerto Rico, with references to Haitian poetics and feminist speculative fictions. Considered the world’s oldest colony, the island was under Spanish rule for over four centuries, followed by the U.S.’s invasion during the Spanish-American War in 1898. Whereas Puerto Rico is primarily known through exoticized portrayals, Muñoz tackles its political and ecological crises involving gentrification and displacement as well as its post-military spaces. Aiming to formulate alternative narratives, the artist often works with non-actors from local communities including activists or healers, whom she invites to reenact events from their own popular culture, history, and Indigenous mythology.

Muñoz’s works are rooted in long-term observation, a common practice in ethnography and documentary filmmaking. At the same time, the artist uses film not as a means of classical realism, but as a genre of poetry. That is why she embraces the vocabulary of theater and expanded cinema, consciously blurring the boundaries between fact and fiction. Inviting improvisation and chance, she explores the potential for re-writing history.

The confusing yet vivid state that emerges when the existing is disordered but new meaning hasn’t developed yet may feel uncomfortable in its arbitrariness—there is nothing solid, no logic or reason to hold on to in Muñoz’s new films—but it is also full of alternative readings, invention, play and possibilities. Or as the artist puts it: “I try to push forward at least a little bit the dissolution of an order that, too reliant on reason, might be blocking the view.”

The publication accompanying the exhibition Elogio al disparate documents an email conversation between the artist and Puerto Rican writer Claudia Becerra. In this dialogue, they exchange thoughts on the concept of nonsense and jitanjáforas, allowing themselves to drift in a spirit of free association while resisting the urge to impose form or meaning on everything. At the center of this exchange are excerpts and poems by Latin American authors such as Clarice Lispector, Alfonso Reyes, Alejandra Pizarnik, Mariano Brull, Francisco Matos Paoli, César Vallejo, José Carlos Mariátegui, Martín Adán, and Bobby Capó. Their texts are presented as a removable book within the book, shaping the artistic intervention.

Curated by Bettina Spörr