Rossella Biscotti

05 Jul - 01 Sep 2013

ROSSELLA BISCOTTI

The Side Room

5 July – 1 September 2013

Events in recent history and politics usually form the starting point for Rossella Biscotti’s projects. She is also interested in issues and insights in the social and natural sciences, particularly in studies and experiments involving memory and dreams. Whether doing research or conducting conversations and interviews with people involved in events or contemporary eyewitnesses, her method of working is always based on dialogue and guided by her quest for formally compelling solutions for her exhibitions. Her preferred media are “poor” materials such as concrete, iron, lead, chipboard, or more recently compost, which Biscotti relates to her subject matters and uses to draw together the various strands of narratives.

Even now, when I make a sculpture I think about narration, but specifically how to edit together stories, ideas, histories, and other information.

Over the past year, the Italian artist has taken part in three of Europe’s preeminent recurring exhibitions: Manifesta 9 in Genk, dOCUMENTA (13) in Kassel, and the 55th Venice Biennale. Her best-known and largest work so far is The Trial (2010–12), a multimedia installation consisting of sculptures, audio collages, videos, and performances, for which she received the Premio Italia Arte Contemporanea prize in 2010 and which was shown at dOCUMENTA (13) in 2012. The work is based on the so-called “Processo 7 aprile” (the April 7 trial) in Rome. On April 7, 1979, members of the revolutionary left (from the groups Potere Operaio and Autonomia Operaia), mostly intellectuals, authors, and professionals in various fields, were arrested on charges of terrorist activity.

The most prominent defendants were the philosophers Paolo Virno and Antonio Negri, who was accused of being the mastermind behind the kidnapping and assassination of the Christian Democratic leader Aldo Moro by the Brigate Rosse (Red Brigades). The trial took place from 1982 to 1984 in the so-called Aula Bunker, a rationalist-style building constructed in the 1930s as a fencing academy that was later adapted for its function as a high-security courthouse. For The Trial, Biscotti made concrete casts of elements of the building, such as the cages for the defendants, and displayed these along with an audio piece, a six-hour editing of the original court recordings from the trial. The installation is often accompanied by simultaneous translation performances both by professional and non-professional interpreters.

Rossella Biscotti’s latest work, I dreamt that you changed into a cat... gatto... ha ha ha, was created for this year’s Venice Biennale, where it can currently be seen in the Arsenale as part of the exhibition Il Palazzo Enciclopedico curated by Massimiliano Gioni. For this project, Biscotti held a dream workshop (Laboratorio Onirico) lasting several months with a group of fourteen inmates of the Venetian women’s prison on Giudecca Island.

I was trying to create a space to exchange dreams, a space to see how we inhabit institutions in general, but more so how personal relations are narrated through institutions such as this prison specifically. [...] These dreams themselves tended to focus on each person’s night dreams; however, in our conversations there was a constant shift from dreams to reality and back again.

In a parallel process, she took up the prison’s practice of composting waste from its own garden. Together with the inmates, Biscotti changed the composition of the compost for the duration of the project by adding leftover food collected by the prisoners.

Since this compost was dedicated to the project, the girls knew it would go outside the prison and represent their lives in the Biennale.

The volume of compost was what ultimately determined the size of Biscotti’s sculptures in the Arsenale: shapes formed out of compost reminiscent of fragments of foundations, which in turn were derived from dreams from the dream workshop.

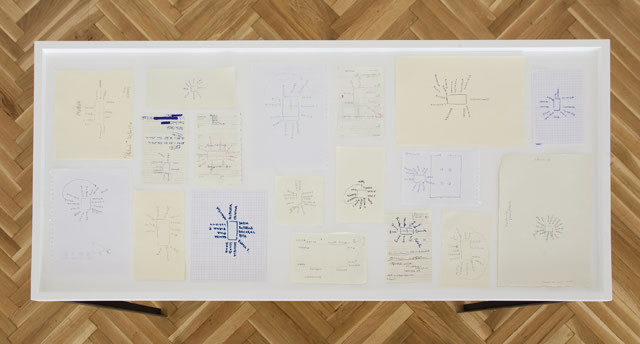

In The Side Room, her first solo exhibition in Austria, Biscotti shows a completely different side of her Venetian dream project in the Grafisches Kabinett of the Secession. An audio editing from the Laboratorio Onirico allows the women participating in the project to speak for themselves. In an hour-long recording, Cristina, Daniela, Diana, Elena F., Elena S., Hanan, Luciana, Manuela, Pina, Racheal, Rita, Roberta, Samira, and Suad relate their dreams, sometimes interrupted by questions and comments from the others. Portraits of the speakers made by Roberta Baseggio—the only one of the dreamers whose full name we learn—hang on the walls, standing in for people who cannot be present. Sketches of seating arrangements from the workshops presented in a display case are a metaphor for the sensitive structure of a group as well as for space and architecture as determining factors of social interaction. If the absence of the speakers finds an equivalent in the deliberately spare setup of the room, the physical presence of the wrought-iron furniture designed by Biscotti constitutes the antithesis to the immateriality of the audio installation and the disembodied portraits.

It was about looking at how to go back and forth between the institutional and the individual, the group and the person. What is most important in this project is how a collective moment is formed, and how to keep that open.

One project that Rossella Biscotti initiated specially for the exhibition at the Secession appears only in the publication, which she envisaged as a kind of extension to the exhibition that would create an unusual connection between two autonomous projects. When the artist arrived in Vienna to prepare her exhibition, the special organizational form of the Secession as an exhibition venue run by an association of artists based on democratic principles awakened her interest and moved her to spontaneously invite the board responsible for the exhibition program to take part in a dream project as well. For the Vienna dream project, in which eight members of the board participated, a non-public blog was set up in which participants could post their dreams anonymously either as texts or visually in the form of drawings or photos and thus share them with one another. In this way, the collection of “dream material” also became available to the artist. Taken together, the two dream projects were intended to examine from various perspectives the relationship between dreams and the institutional setting and the impact they have on one another.

“According to Erving Goffman, a total institution such as a penitentiary represents an extreme example of a ‘social institution,’ while an exhibition venue for contemporary art is situated at the other extreme of this scale. Motivated by this tension between the two extremes, Biscotti anticipated that her dual research might generate new readings and unexpected associations.”(2)

In addition to the dream project with the board, Biscotti also turned her attention to the architecture and architectural history of the Secession. In the complete refurbishment of the Secession carried out by the Vienna architect Adolf Krischanitz in 1985–86, which involved reconciling the need to protect a historic building with architectural archaeology and the requirements of a modern exhibition venue, Biscotti identified a turning point and element of renewal in the history of the association of artists. In conjunction with her board project, she chose to concentrate on Krischanitz’s furniture designs for the conference room and on the color scheme devised by Oskar Putz, which used to encompass the entire building but is now preserved in its complete form only in the conference room. Biscotti subsequently conducted research in the Secession’s archive and held conversations with Adolf Krischanitz and Oskar Putz. Putz’s color system, which consisted of forty-three colors specially created for the Secession, was reconstructed for the catalogue, where it serves as a central element: just as the portraits of the female prisoners represent the women themselves or, more precisely, their absence, so the colors, to Biscotti’s mind, represent the Secession itself roughly as architectural plans would. The pages of color intercalated throughout the catalogue form a visual bridge between the two dream projects.

Invited by the board of the Secession

Curated by Bettina Spörr

(1) If not stated otherwise, all quotes are taken from: “On Art and Dreaming: The Singular and the Collective from Cement to Compost—An Interview with Rossella Biscotti by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev”, in: Rossella Biscotti (exhibition catalogue), Secession, Vienna 2013.

(2) Spörr, Bettina. “Dream Space: Rossella Biscotti’s project with the board of the Secession”, in: Rossella Biscotti (exhibition catalogue), Secession, Vienna 2013, p. 15.

The Side Room

5 July – 1 September 2013

Events in recent history and politics usually form the starting point for Rossella Biscotti’s projects. She is also interested in issues and insights in the social and natural sciences, particularly in studies and experiments involving memory and dreams. Whether doing research or conducting conversations and interviews with people involved in events or contemporary eyewitnesses, her method of working is always based on dialogue and guided by her quest for formally compelling solutions for her exhibitions. Her preferred media are “poor” materials such as concrete, iron, lead, chipboard, or more recently compost, which Biscotti relates to her subject matters and uses to draw together the various strands of narratives.

Even now, when I make a sculpture I think about narration, but specifically how to edit together stories, ideas, histories, and other information.

Over the past year, the Italian artist has taken part in three of Europe’s preeminent recurring exhibitions: Manifesta 9 in Genk, dOCUMENTA (13) in Kassel, and the 55th Venice Biennale. Her best-known and largest work so far is The Trial (2010–12), a multimedia installation consisting of sculptures, audio collages, videos, and performances, for which she received the Premio Italia Arte Contemporanea prize in 2010 and which was shown at dOCUMENTA (13) in 2012. The work is based on the so-called “Processo 7 aprile” (the April 7 trial) in Rome. On April 7, 1979, members of the revolutionary left (from the groups Potere Operaio and Autonomia Operaia), mostly intellectuals, authors, and professionals in various fields, were arrested on charges of terrorist activity.

The most prominent defendants were the philosophers Paolo Virno and Antonio Negri, who was accused of being the mastermind behind the kidnapping and assassination of the Christian Democratic leader Aldo Moro by the Brigate Rosse (Red Brigades). The trial took place from 1982 to 1984 in the so-called Aula Bunker, a rationalist-style building constructed in the 1930s as a fencing academy that was later adapted for its function as a high-security courthouse. For The Trial, Biscotti made concrete casts of elements of the building, such as the cages for the defendants, and displayed these along with an audio piece, a six-hour editing of the original court recordings from the trial. The installation is often accompanied by simultaneous translation performances both by professional and non-professional interpreters.

Rossella Biscotti’s latest work, I dreamt that you changed into a cat... gatto... ha ha ha, was created for this year’s Venice Biennale, where it can currently be seen in the Arsenale as part of the exhibition Il Palazzo Enciclopedico curated by Massimiliano Gioni. For this project, Biscotti held a dream workshop (Laboratorio Onirico) lasting several months with a group of fourteen inmates of the Venetian women’s prison on Giudecca Island.

I was trying to create a space to exchange dreams, a space to see how we inhabit institutions in general, but more so how personal relations are narrated through institutions such as this prison specifically. [...] These dreams themselves tended to focus on each person’s night dreams; however, in our conversations there was a constant shift from dreams to reality and back again.

In a parallel process, she took up the prison’s practice of composting waste from its own garden. Together with the inmates, Biscotti changed the composition of the compost for the duration of the project by adding leftover food collected by the prisoners.

Since this compost was dedicated to the project, the girls knew it would go outside the prison and represent their lives in the Biennale.

The volume of compost was what ultimately determined the size of Biscotti’s sculptures in the Arsenale: shapes formed out of compost reminiscent of fragments of foundations, which in turn were derived from dreams from the dream workshop.

In The Side Room, her first solo exhibition in Austria, Biscotti shows a completely different side of her Venetian dream project in the Grafisches Kabinett of the Secession. An audio editing from the Laboratorio Onirico allows the women participating in the project to speak for themselves. In an hour-long recording, Cristina, Daniela, Diana, Elena F., Elena S., Hanan, Luciana, Manuela, Pina, Racheal, Rita, Roberta, Samira, and Suad relate their dreams, sometimes interrupted by questions and comments from the others. Portraits of the speakers made by Roberta Baseggio—the only one of the dreamers whose full name we learn—hang on the walls, standing in for people who cannot be present. Sketches of seating arrangements from the workshops presented in a display case are a metaphor for the sensitive structure of a group as well as for space and architecture as determining factors of social interaction. If the absence of the speakers finds an equivalent in the deliberately spare setup of the room, the physical presence of the wrought-iron furniture designed by Biscotti constitutes the antithesis to the immateriality of the audio installation and the disembodied portraits.

It was about looking at how to go back and forth between the institutional and the individual, the group and the person. What is most important in this project is how a collective moment is formed, and how to keep that open.

One project that Rossella Biscotti initiated specially for the exhibition at the Secession appears only in the publication, which she envisaged as a kind of extension to the exhibition that would create an unusual connection between two autonomous projects. When the artist arrived in Vienna to prepare her exhibition, the special organizational form of the Secession as an exhibition venue run by an association of artists based on democratic principles awakened her interest and moved her to spontaneously invite the board responsible for the exhibition program to take part in a dream project as well. For the Vienna dream project, in which eight members of the board participated, a non-public blog was set up in which participants could post their dreams anonymously either as texts or visually in the form of drawings or photos and thus share them with one another. In this way, the collection of “dream material” also became available to the artist. Taken together, the two dream projects were intended to examine from various perspectives the relationship between dreams and the institutional setting and the impact they have on one another.

“According to Erving Goffman, a total institution such as a penitentiary represents an extreme example of a ‘social institution,’ while an exhibition venue for contemporary art is situated at the other extreme of this scale. Motivated by this tension between the two extremes, Biscotti anticipated that her dual research might generate new readings and unexpected associations.”(2)

In addition to the dream project with the board, Biscotti also turned her attention to the architecture and architectural history of the Secession. In the complete refurbishment of the Secession carried out by the Vienna architect Adolf Krischanitz in 1985–86, which involved reconciling the need to protect a historic building with architectural archaeology and the requirements of a modern exhibition venue, Biscotti identified a turning point and element of renewal in the history of the association of artists. In conjunction with her board project, she chose to concentrate on Krischanitz’s furniture designs for the conference room and on the color scheme devised by Oskar Putz, which used to encompass the entire building but is now preserved in its complete form only in the conference room. Biscotti subsequently conducted research in the Secession’s archive and held conversations with Adolf Krischanitz and Oskar Putz. Putz’s color system, which consisted of forty-three colors specially created for the Secession, was reconstructed for the catalogue, where it serves as a central element: just as the portraits of the female prisoners represent the women themselves or, more precisely, their absence, so the colors, to Biscotti’s mind, represent the Secession itself roughly as architectural plans would. The pages of color intercalated throughout the catalogue form a visual bridge between the two dream projects.

Invited by the board of the Secession

Curated by Bettina Spörr

(1) If not stated otherwise, all quotes are taken from: “On Art and Dreaming: The Singular and the Collective from Cement to Compost—An Interview with Rossella Biscotti by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev”, in: Rossella Biscotti (exhibition catalogue), Secession, Vienna 2013.

(2) Spörr, Bettina. “Dream Space: Rossella Biscotti’s project with the board of the Secession”, in: Rossella Biscotti (exhibition catalogue), Secession, Vienna 2013, p. 15.