Ada Lovelace

The Enchantress of Numbers

29 Apr - 15 Oct 2017

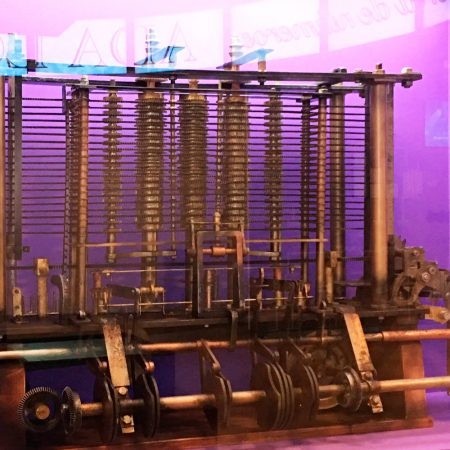

Reproduction of a fragment of The Analytical Engine currently being exhibited at the Science Museum in London.

ADA LOVELACE

The Enchantress of Numbers

29 April - 15 October 2017

Ada Lovelace was a woman of privileged intelligence, a bold visionary who lived a life that, in many respects, bucked the trends of her era. Here we present a small format exhibition about this forward-thinking woman who could identify in a calculating machine that the future was in computing.

The first ever programmer

One of the goals of this exhibition space is to give exposure and recognition to little known or forgotten female inventors. First it was the actress Hedy Lamarr and her secret communication system, followed by the teacher Angelita Ruiz and her innovative mechanical encyclopedia, and now it is the turn of the extraordinary British mathematician Ada Lovelace.

An essential figure for understanding the current computer age and acknowledged to be the first programmer in history, Ada Lovelace was a woman of privileged intelligence, a bold visionary who lived a life that, in many respects, bucked the trends of her era.

This small format exhibition – on the second floor of the Espacio Fundación Telefónica until 15 October – provides a brief journey through some of the essential milestones in her life story: the unconventional education for a woman of her times, her delicate health, the admiration of many of her contemporaries and her productive intellectual exchanges with many of them – above all Babbage – and, of course, her main contribution: being acknowledged as the first ever computer programmer.

A masculine education for an extraordinary woman

Ada Augusta Gordon was born in 1815, in London, the only legitimate daughter of George Gordon –Lord Byron– and Anne Isabelle Milbanke. Her mother Annabella was the only child of an affluent family with excellent political connections. Intelligent and with progressive ideas, she had an education that was unusual for a woman of her time. Byron called her his “princess of the parallelograms” due to her knowledge and passion for mathematics.

Lady Byron submitted her daughter to a strict education with the intention of eliminating any trace of irrationality or ‘poetic’ influence inherited from her father. Her education was imparted by various different tutors, mentors and governesses: her unconventional curriculum included French, music, German, Latin and Greek, history and, of course, science and mathematics. At twelve years old, Ada became so obsessed with the idea of flying that she wrote a treatise on her research: she dissected birds, studied anatomy, made mathematical calculations of it; analysed materials for making wings: feathers, paper, wire, etc.

In terms of mathematical knowledge, she soon left her mother and her first teachers behind. She asked Mary Somerville, a renowned scientist, to be her tutor. With her, she kept up an intense correspondence on advanced mathematics.

Brilliant, intrepid and well-known horse lover, it would appear that Lady Lovelace was not exactly a perfect fit in rigid Victorian society.

The great encounter of her life: Charles Babbage

When Ada was just 18 years old she met Charles Babbage, the person who would influence her the most and with whom she maintained a lifelong friendship and collaboration.

Babbage was a rich and famous inventor. He was also extremely talented: he was the holder of the Lucasian Chair of Mathematics at Cambridge, previously held by Newton and later occupied by renowned scientists such as Stephen Hawking: Darwin, Dickens, Florence Nightingale, the Duke of Wellington, Augustus de Morgan, Lord Tennyson, Faraday, Wheatstone were regulars at his soirées.

At these gatherings, Babbage used to delight in showing off one of his inventions: a fragment of an automatic calculating machine: the Difference Engine. According to one of the guests, when Ada saw this model she understood immediately how it worked and was able to appreciate ‘the beauty of the invention’.

The Analytical Engine

While Babbage was working on his Difference Engine he had another idea for a more advanced machine: the Analytical Engine, designed to be able to do any type of mathematical calculation. Composed of high columns of stacked cogwheels, interlinked by gears and levers and powered by a steam engine, it is today considered as the forerunner of modern computers. It was programmed by means of punch cards that were used to operate the machine and could also be used for storing data.

In the thousands of notes and drawings about the Analytical Engine that Babbage sent to Ada, nearly all the basic features and elements incorporated into modern computers were described: input and output devices, memory and processor. But it was never built. The technology of the time was not advanced enough to manufacture its thousands of components.

The contributions of Ada Lovelace

In 1840, the mathematician Charles Babbage gave a lecture on his invention in Turin. In the audience was Luigi Federico Menabrea, a military engineer who would later become Prime Minister of Italy. Menabrea, impressed by Babbage’s machine, wrote an article in a French journal entitled ‘Sketch of the Analytical Engine’. It is the only published document about this extraordinary device in which he describes the basic structure of the machine.

Ada Lovelace, at the request of the scientist and inventor Charles Wheatstone, translated this article into English, adding to it a series of explanatory notes. These notes more than doubled the length of Menabrea’s original text and made the publication one of the most important documents in the history of computing, thanks to the contribution of Ada Lovelace’s genius.

These notes by Ada contain the precursors to many modern programming ideas such as loops, statements and the concept of general purpose computing.

Beyond solving numerical equations, Lovelace put forward the possibility that by manipulating symbols then one could operate on any kind of information, not just numbers. In an age before the introduction of mathematics into logic, this concept represented an extraordinary and revolutionary advance.

Ada included an algorithm in the notes that showed exactly how the machine could be used to compute a complex sequence of numbers. Lovelace went far beyond a mere academic consideration of the potential of the Analytical Engine and created the first ever computer programme. In these columns of gears, she was able to see a general purpose machine, capable of manipulating symbols and information and producing results with no human intervention.

A key element: punch cards

For Babbage’s extraordinary machine to work, Lovelace explained in Note A to Menabrea’s document how it would receive information about the function to be carried out by means of punch cards. In the same way, the results could also be output by the machine by punching these cards. It would also be possible to organise the cards in such a way that the machine could perform a long and complicated programme without human intervention.

This system of punch cards was use to programme the first computers from the 1950s up to the mid-1980s of the 20th century, years after the deaths of Lovelace and Babbage.

In collaboration with:

Museo del Romanticismo. Madrid

Museo de la Farmacia Hispana – Historical Heritage Complutense University of Madrid.

Museo de Medicina Infanta Margarita. Royal National Academy of Medicine

Museu de la Ciència i de la Tècnica de Catalunya. Terrassa, Barcelona

Heinz Nixdorf MuseumsForum. Paderborn (Germany)

The Enchantress of Numbers

29 April - 15 October 2017

Ada Lovelace was a woman of privileged intelligence, a bold visionary who lived a life that, in many respects, bucked the trends of her era. Here we present a small format exhibition about this forward-thinking woman who could identify in a calculating machine that the future was in computing.

The first ever programmer

One of the goals of this exhibition space is to give exposure and recognition to little known or forgotten female inventors. First it was the actress Hedy Lamarr and her secret communication system, followed by the teacher Angelita Ruiz and her innovative mechanical encyclopedia, and now it is the turn of the extraordinary British mathematician Ada Lovelace.

An essential figure for understanding the current computer age and acknowledged to be the first programmer in history, Ada Lovelace was a woman of privileged intelligence, a bold visionary who lived a life that, in many respects, bucked the trends of her era.

This small format exhibition – on the second floor of the Espacio Fundación Telefónica until 15 October – provides a brief journey through some of the essential milestones in her life story: the unconventional education for a woman of her times, her delicate health, the admiration of many of her contemporaries and her productive intellectual exchanges with many of them – above all Babbage – and, of course, her main contribution: being acknowledged as the first ever computer programmer.

A masculine education for an extraordinary woman

Ada Augusta Gordon was born in 1815, in London, the only legitimate daughter of George Gordon –Lord Byron– and Anne Isabelle Milbanke. Her mother Annabella was the only child of an affluent family with excellent political connections. Intelligent and with progressive ideas, she had an education that was unusual for a woman of her time. Byron called her his “princess of the parallelograms” due to her knowledge and passion for mathematics.

Lady Byron submitted her daughter to a strict education with the intention of eliminating any trace of irrationality or ‘poetic’ influence inherited from her father. Her education was imparted by various different tutors, mentors and governesses: her unconventional curriculum included French, music, German, Latin and Greek, history and, of course, science and mathematics. At twelve years old, Ada became so obsessed with the idea of flying that she wrote a treatise on her research: she dissected birds, studied anatomy, made mathematical calculations of it; analysed materials for making wings: feathers, paper, wire, etc.

In terms of mathematical knowledge, she soon left her mother and her first teachers behind. She asked Mary Somerville, a renowned scientist, to be her tutor. With her, she kept up an intense correspondence on advanced mathematics.

Brilliant, intrepid and well-known horse lover, it would appear that Lady Lovelace was not exactly a perfect fit in rigid Victorian society.

The great encounter of her life: Charles Babbage

When Ada was just 18 years old she met Charles Babbage, the person who would influence her the most and with whom she maintained a lifelong friendship and collaboration.

Babbage was a rich and famous inventor. He was also extremely talented: he was the holder of the Lucasian Chair of Mathematics at Cambridge, previously held by Newton and later occupied by renowned scientists such as Stephen Hawking: Darwin, Dickens, Florence Nightingale, the Duke of Wellington, Augustus de Morgan, Lord Tennyson, Faraday, Wheatstone were regulars at his soirées.

At these gatherings, Babbage used to delight in showing off one of his inventions: a fragment of an automatic calculating machine: the Difference Engine. According to one of the guests, when Ada saw this model she understood immediately how it worked and was able to appreciate ‘the beauty of the invention’.

The Analytical Engine

While Babbage was working on his Difference Engine he had another idea for a more advanced machine: the Analytical Engine, designed to be able to do any type of mathematical calculation. Composed of high columns of stacked cogwheels, interlinked by gears and levers and powered by a steam engine, it is today considered as the forerunner of modern computers. It was programmed by means of punch cards that were used to operate the machine and could also be used for storing data.

In the thousands of notes and drawings about the Analytical Engine that Babbage sent to Ada, nearly all the basic features and elements incorporated into modern computers were described: input and output devices, memory and processor. But it was never built. The technology of the time was not advanced enough to manufacture its thousands of components.

The contributions of Ada Lovelace

In 1840, the mathematician Charles Babbage gave a lecture on his invention in Turin. In the audience was Luigi Federico Menabrea, a military engineer who would later become Prime Minister of Italy. Menabrea, impressed by Babbage’s machine, wrote an article in a French journal entitled ‘Sketch of the Analytical Engine’. It is the only published document about this extraordinary device in which he describes the basic structure of the machine.

Ada Lovelace, at the request of the scientist and inventor Charles Wheatstone, translated this article into English, adding to it a series of explanatory notes. These notes more than doubled the length of Menabrea’s original text and made the publication one of the most important documents in the history of computing, thanks to the contribution of Ada Lovelace’s genius.

These notes by Ada contain the precursors to many modern programming ideas such as loops, statements and the concept of general purpose computing.

Beyond solving numerical equations, Lovelace put forward the possibility that by manipulating symbols then one could operate on any kind of information, not just numbers. In an age before the introduction of mathematics into logic, this concept represented an extraordinary and revolutionary advance.

Ada included an algorithm in the notes that showed exactly how the machine could be used to compute a complex sequence of numbers. Lovelace went far beyond a mere academic consideration of the potential of the Analytical Engine and created the first ever computer programme. In these columns of gears, she was able to see a general purpose machine, capable of manipulating symbols and information and producing results with no human intervention.

A key element: punch cards

For Babbage’s extraordinary machine to work, Lovelace explained in Note A to Menabrea’s document how it would receive information about the function to be carried out by means of punch cards. In the same way, the results could also be output by the machine by punching these cards. It would also be possible to organise the cards in such a way that the machine could perform a long and complicated programme without human intervention.

This system of punch cards was use to programme the first computers from the 1950s up to the mid-1980s of the 20th century, years after the deaths of Lovelace and Babbage.

In collaboration with:

Museo del Romanticismo. Madrid

Museo de la Farmacia Hispana – Historical Heritage Complutense University of Madrid.

Museo de Medicina Infanta Margarita. Royal National Academy of Medicine

Museu de la Ciència i de la Tècnica de Catalunya. Terrassa, Barcelona

Heinz Nixdorf MuseumsForum. Paderborn (Germany)