Americana: Maine

31 Mar - 18 Apr 2009

AMERICANA: MAINE

Malaga Island: No Man's Land

Mary Augustine Gallery

Mar. 31–Apr. 18, 2009

At the turn of the twentieth century, a popular postcard titled The Deuce of Spades was widely distributed throughout New England. The postcard featured Malaga Island. However, instead of depicting a picturesque vacation destination or unspoiled wilderness, it bore the image of two people of color—an aging woman and a young child—and is emblazoned with a racial slur.

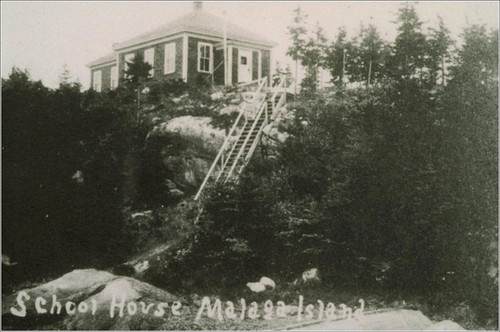

The mythic Maine, once promoted by the Maine Central Railroad as "Vacationland," has long been at odds with the harsh realities of year-round life in one of the poorest states in the nation. In 2009, tourism remains the most important moneymaking industry in Maine, but the positive aspects of tourism can veil remnants of a disturbing history. In the early 1900s, as the Maine Coast was quickly transforming into a desirable vacation destination, the mixed-race community of Malaga Island began to attract an increasing level of public attention. In a state that is predominately white, the islanders were what remained of a 52 year-old community of black, white, and Native American residents that is thought to have been founded by the descendants of Benjamin Darling, a freed slave. As sensationalized reports of "degenerate colonies" were published in Maine newspapers, residents of nearby Phippsburg grew tired of supporting a "pauper community" that damaged the area's reputation and in 1905 passed legislation that placed Malaga under state control. In 1911, the state forced an entire Malaga family to enter the Maine School for the Feeble-Minded, which was constructed at the height of the eugenics movement to remove "poor unfortunates" from view. By 1912, the remaining residents of the island were evicted. To ensure that the islanders did not return, the state relocated the schoolhouse, removed the remaining cottages, dug up the cemetery, and reburied the remains on the grounds of the mental hospital.

It was not until 2006, when professors and students from the University of Southern Maine conducted the first archaeological excavation on Malaga, that the actual history of the community was understood. The recently unearthed fragments of glass, shell, and ceramic displayed in this exhibition refute old newspaper accounts of a helpless community in need of removal. As USM Associate Professor of Archaeology Nathan Hamilton emphasizes, "Malaga Island looks a lot like any other working community at the turn of the century."

Malaga Island was never resettled, and remains empty to this day—a monument to racism, intolerance, and displacement.

Curated by Jaime Austin

Special thanks to Nathan Hamilton, Ingrid Brack, and the University of Southern Maine Department of Archaeology

Malaga Island: No Man's Land

Mary Augustine Gallery

Mar. 31–Apr. 18, 2009

At the turn of the twentieth century, a popular postcard titled The Deuce of Spades was widely distributed throughout New England. The postcard featured Malaga Island. However, instead of depicting a picturesque vacation destination or unspoiled wilderness, it bore the image of two people of color—an aging woman and a young child—and is emblazoned with a racial slur.

The mythic Maine, once promoted by the Maine Central Railroad as "Vacationland," has long been at odds with the harsh realities of year-round life in one of the poorest states in the nation. In 2009, tourism remains the most important moneymaking industry in Maine, but the positive aspects of tourism can veil remnants of a disturbing history. In the early 1900s, as the Maine Coast was quickly transforming into a desirable vacation destination, the mixed-race community of Malaga Island began to attract an increasing level of public attention. In a state that is predominately white, the islanders were what remained of a 52 year-old community of black, white, and Native American residents that is thought to have been founded by the descendants of Benjamin Darling, a freed slave. As sensationalized reports of "degenerate colonies" were published in Maine newspapers, residents of nearby Phippsburg grew tired of supporting a "pauper community" that damaged the area's reputation and in 1905 passed legislation that placed Malaga under state control. In 1911, the state forced an entire Malaga family to enter the Maine School for the Feeble-Minded, which was constructed at the height of the eugenics movement to remove "poor unfortunates" from view. By 1912, the remaining residents of the island were evicted. To ensure that the islanders did not return, the state relocated the schoolhouse, removed the remaining cottages, dug up the cemetery, and reburied the remains on the grounds of the mental hospital.

It was not until 2006, when professors and students from the University of Southern Maine conducted the first archaeological excavation on Malaga, that the actual history of the community was understood. The recently unearthed fragments of glass, shell, and ceramic displayed in this exhibition refute old newspaper accounts of a helpless community in need of removal. As USM Associate Professor of Archaeology Nathan Hamilton emphasizes, "Malaga Island looks a lot like any other working community at the turn of the century."

Malaga Island was never resettled, and remains empty to this day—a monument to racism, intolerance, and displacement.

Curated by Jaime Austin

Special thanks to Nathan Hamilton, Ingrid Brack, and the University of Southern Maine Department of Archaeology