Timm Ulrichs

18 Sep - 18 Oct 2014

Timm Ulrichs

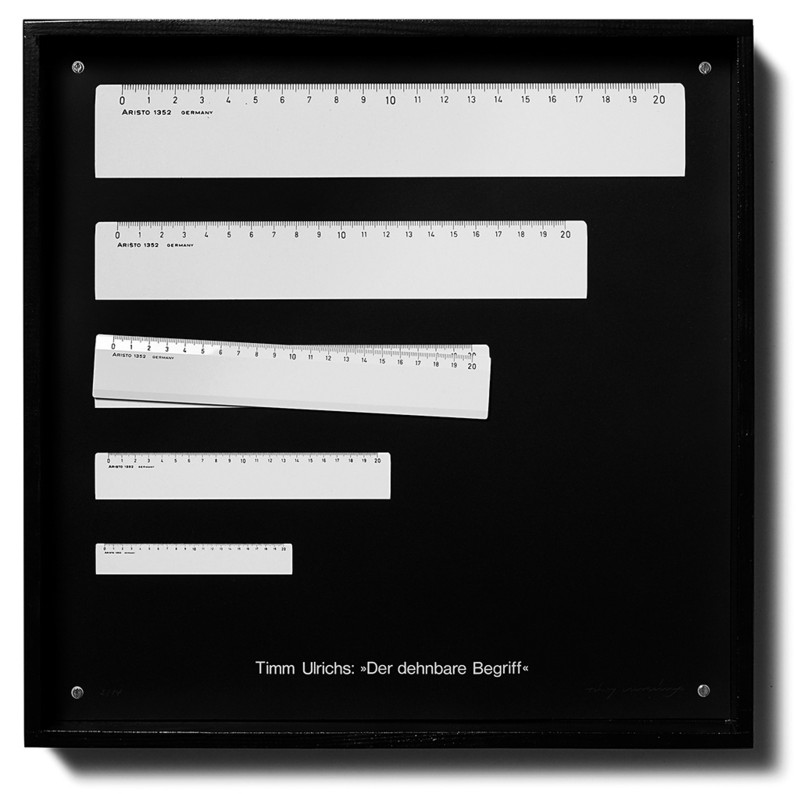

"Der dehnbare Begriff (the flexible concept)", 1966/1975

wooden case, silk-screen print, plastic ruler

40 x 40 x 5 cm

"Der dehnbare Begriff (the flexible concept)", 1966/1975

wooden case, silk-screen print, plastic ruler

40 x 40 x 5 cm

TIMM ULRICHS

8 1⁄2 Meisterwerke

18 September – 18 October 2014

Timm Ulrich’s solo exhibition brings together works of the last five decades that deal with fathoming and measuring, that call numbers into question, and that highlight addition, filling after emptying and displacing as artistic strategies. As such Ulrichs chisels a through out of block of sandstone to fill it with its own content in 1969 e.g. or makes six identical copies of a genuine quarzite stone, only that they very in size, while the gestalt remains the same. 8 1/2 Masterpieces demonstrates how the ostensibly unique or absolute yields so much more when it becomes altered, augmented, displaced, or even multiplied – even at times just by half.

Eight masterpieces and a half? There’s something questionable inherent in the plural of the artist’s masterpiece, since it effectively subverts its own meaning: to create something so outstanding that it seems impossible to repeat. Nevertheless, it is probably possible to succeed at trumping one masterpiece with the next. But a half?

The solo exhibition of “image-inventor” and “image-discoverer” Timm Ulrichs brings together works from the last five decades that deal with measuring and fathoming, that call numbers into question, and that highlight addition and substitution, filling after emptying, and displacing as artistic strategies. His Wachsender Stein (growing stone, 2008/12) takes a genuine quartzite as its starting point; it has six identical copies that vary solely in dimension and, as bronzes, cannot be distinguished from their original. Except in size. But which one is the genuine one?

Ulrichs had already, in 1966, demonstrated something similar with his work Der dehnbarer Begriff [the flexible concept]: a standard 20 cm long ruler, brand name aristo, sits in a glass box on a 1 : 1 photographic reproduction of itself. Next to it are images of the same ruler, enlarged and reduced in size. To neither the natural stone nor the ruler do we attribute the ontological flexibility that Ulrichs’s objects phenomenologically demonstrate for us. Because the centimeter is defined by a humanly determined, arbitrarily assigned value as a universal and immutable unit of length, even as the stone is seen as a one-of-a-kind object, its uniqueness shaped by the forces of nature. Timm Ulrichs’s stones and rulers captivate us with their unanticipated flexibility.

Ulrichs also seemingly shifts the earth’s center of gravity in the exhibition space when he suspends a plumb-line from the ceiling that quite obviously hangs not perpendicular to the floor but at an angle — as if other rules apply in his world. In another work, rectangular electrical magnetic plates are arranged like dominos on the floor, except these dominos all stand at an angle and move when voltage is applied. They mutually repel and never touch. This work’s title, Laputa (1985), refers to the flying island from Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, which is inhabited by enthusiastic mathematicians, physicists and other natural scientists whose measurements nevertheless constantly go awry, due among other things to the island’s magnetic core, which is what enables it to levitate in the first place. All of its buildings therefore stand quite crookedly and its inhabitants’ clothing never fits.

Trog, sich selbst beinhaltend (trough, containing itself 1969), Form und Inhalt (15 x 1 Liter) (form and content, 1982) and Rekonstruktionen (1988) are examples of works that ponder shifting gestalts. Ulrichs chisels a trough out of a block of sandstone and fills it with its own contents, or he takes each of the 16 individual fragments of a broken flowerpot as the starting point for a complete reconstruction of the original object. The trough physically contains the identical mass, however it generates a function for itself — it contains itself. According to the number of fragments resulting from the flowerpot’s destruction, Ulrichs reconstitutes a family of new, yet identical forms.

The exhibition title’s most obvious reference alludes to Federico Fellini’s film masterpiece 8 1/2 from 1963. After all, Fellini made being a director itself, the entanglement and nesting of different (filmic) realities, the leitmotif of his eight-and-a-half films as director. The exhibition at WENTRUP traces not just Ulrichs’s various attempts at “[looking] behind the scenes and [observing] things from all sides in order to realize “how polyvalent they are.” 8 1/2 Masterpieces demonstrates how the ostensibly unique or absolute yields so much more when it becomes altered, augmented, displaced, or even multiplied – even at times just by half.

In 1969 Timm Ulrichs first solo exhibition took place at Museum Haus Lange in Krefeld, in the same year he also took part in the seminal exhibition “Konzeption – conception” (curated by Konrad Fischer) held at the Museum Morsbroich in Leverkusen, and which introduced Conceptual Art to the Federal Republic of Germany. 8 years later Ulrichs participated in documenta 6. Since then, Ulrichs had numerous international solo exhibitions and participated in group exhibitions, among them at Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, Centre Pompidou, ZKM Karlsruhe, Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin, Museum der Moderne in Salzburg, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Haus der Kunst in Munich, and Kestnergesellschaft Hannover. On the occasion of his 70th birthday in 2010 the Sprengel Museum and Kunstverein Hanover have honoured Timm Ulrichs with a comprehensive retrospective exhibition.

For his work, Timm Ulrichs has received as well numerous international prizes. Museum collections that own works by Timm Ulrichs include The Museum of Modern Art, Centre Pompidou, ZKM Karlsruhe, Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin, Sprengel Museum Hannover, Museum Abteiberg Mönchengladbach, Museum Ludwig Cologne and others.

His early performances and happenings have art historical significance in terms of determining an avant-garde art after 1960.

Timm Ulrichs’s 8 1⁄2 Meisterwerke and Cevdet Erek’s jahrundtagundtag were conceived as parallel exhibitions for WENTRUP by Nico Anklam.

8 1⁄2 Meisterwerke

18 September – 18 October 2014

Timm Ulrich’s solo exhibition brings together works of the last five decades that deal with fathoming and measuring, that call numbers into question, and that highlight addition, filling after emptying and displacing as artistic strategies. As such Ulrichs chisels a through out of block of sandstone to fill it with its own content in 1969 e.g. or makes six identical copies of a genuine quarzite stone, only that they very in size, while the gestalt remains the same. 8 1/2 Masterpieces demonstrates how the ostensibly unique or absolute yields so much more when it becomes altered, augmented, displaced, or even multiplied – even at times just by half.

Eight masterpieces and a half? There’s something questionable inherent in the plural of the artist’s masterpiece, since it effectively subverts its own meaning: to create something so outstanding that it seems impossible to repeat. Nevertheless, it is probably possible to succeed at trumping one masterpiece with the next. But a half?

The solo exhibition of “image-inventor” and “image-discoverer” Timm Ulrichs brings together works from the last five decades that deal with measuring and fathoming, that call numbers into question, and that highlight addition and substitution, filling after emptying, and displacing as artistic strategies. His Wachsender Stein (growing stone, 2008/12) takes a genuine quartzite as its starting point; it has six identical copies that vary solely in dimension and, as bronzes, cannot be distinguished from their original. Except in size. But which one is the genuine one?

Ulrichs had already, in 1966, demonstrated something similar with his work Der dehnbarer Begriff [the flexible concept]: a standard 20 cm long ruler, brand name aristo, sits in a glass box on a 1 : 1 photographic reproduction of itself. Next to it are images of the same ruler, enlarged and reduced in size. To neither the natural stone nor the ruler do we attribute the ontological flexibility that Ulrichs’s objects phenomenologically demonstrate for us. Because the centimeter is defined by a humanly determined, arbitrarily assigned value as a universal and immutable unit of length, even as the stone is seen as a one-of-a-kind object, its uniqueness shaped by the forces of nature. Timm Ulrichs’s stones and rulers captivate us with their unanticipated flexibility.

Ulrichs also seemingly shifts the earth’s center of gravity in the exhibition space when he suspends a plumb-line from the ceiling that quite obviously hangs not perpendicular to the floor but at an angle — as if other rules apply in his world. In another work, rectangular electrical magnetic plates are arranged like dominos on the floor, except these dominos all stand at an angle and move when voltage is applied. They mutually repel and never touch. This work’s title, Laputa (1985), refers to the flying island from Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, which is inhabited by enthusiastic mathematicians, physicists and other natural scientists whose measurements nevertheless constantly go awry, due among other things to the island’s magnetic core, which is what enables it to levitate in the first place. All of its buildings therefore stand quite crookedly and its inhabitants’ clothing never fits.

Trog, sich selbst beinhaltend (trough, containing itself 1969), Form und Inhalt (15 x 1 Liter) (form and content, 1982) and Rekonstruktionen (1988) are examples of works that ponder shifting gestalts. Ulrichs chisels a trough out of a block of sandstone and fills it with its own contents, or he takes each of the 16 individual fragments of a broken flowerpot as the starting point for a complete reconstruction of the original object. The trough physically contains the identical mass, however it generates a function for itself — it contains itself. According to the number of fragments resulting from the flowerpot’s destruction, Ulrichs reconstitutes a family of new, yet identical forms.

The exhibition title’s most obvious reference alludes to Federico Fellini’s film masterpiece 8 1/2 from 1963. After all, Fellini made being a director itself, the entanglement and nesting of different (filmic) realities, the leitmotif of his eight-and-a-half films as director. The exhibition at WENTRUP traces not just Ulrichs’s various attempts at “[looking] behind the scenes and [observing] things from all sides in order to realize “how polyvalent they are.” 8 1/2 Masterpieces demonstrates how the ostensibly unique or absolute yields so much more when it becomes altered, augmented, displaced, or even multiplied – even at times just by half.

In 1969 Timm Ulrichs first solo exhibition took place at Museum Haus Lange in Krefeld, in the same year he also took part in the seminal exhibition “Konzeption – conception” (curated by Konrad Fischer) held at the Museum Morsbroich in Leverkusen, and which introduced Conceptual Art to the Federal Republic of Germany. 8 years later Ulrichs participated in documenta 6. Since then, Ulrichs had numerous international solo exhibitions and participated in group exhibitions, among them at Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, Centre Pompidou, ZKM Karlsruhe, Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin, Museum der Moderne in Salzburg, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Haus der Kunst in Munich, and Kestnergesellschaft Hannover. On the occasion of his 70th birthday in 2010 the Sprengel Museum and Kunstverein Hanover have honoured Timm Ulrichs with a comprehensive retrospective exhibition.

For his work, Timm Ulrichs has received as well numerous international prizes. Museum collections that own works by Timm Ulrichs include The Museum of Modern Art, Centre Pompidou, ZKM Karlsruhe, Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin, Sprengel Museum Hannover, Museum Abteiberg Mönchengladbach, Museum Ludwig Cologne and others.

His early performances and happenings have art historical significance in terms of determining an avant-garde art after 1960.

Timm Ulrichs’s 8 1⁄2 Meisterwerke and Cevdet Erek’s jahrundtagundtag were conceived as parallel exhibitions for WENTRUP by Nico Anklam.