Wangechi Mutu

25 Jun - 12 Sep 2010

WANGECHI MUTU

My Dirty Little Heaven - Deutsche Bank Artist of the Year 2010

25.06 - 12.09.2010

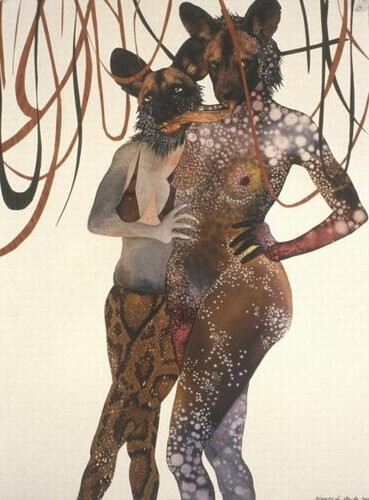

In her work, New York-based artist Wangechi Mutu, who was born in Kenya, addresses issues related to black female identity, Western consumer culture, African politics, and postcolonial history. She became known for her collages that vacillate between beauty and horror. By using various materials such as glitter, tape, or animal fur in combination with magazine clippings, she creates idiosyncratic pieces that present the female body in a distorted, seductive, or commanding way and in a state of constant transformation.

For the exhibition “My Dirty Little Heaven,” Wangechi Mutu transformed the first floor into a suggestive environment, which recalls both a protective cocoon and the improvised buildings found in shanty towns on the peripheries of big cities such as Rio de Janeiro, Lagos, or Cape Town. Mutu seems to be less interested in reflecting on original cultural identity than in providing a vision of a future in which more and more people, as migrants and nomads, are becoming part of the “AlieNation.” In her view, cultural identity is no longer determined by geographical origins, ancestry or biological disposition, but is increasingly becoming a hybrid construct that people can determine and change themselves.

My Dirty Little Heaven - Deutsche Bank Artist of the Year 2010

25.06 - 12.09.2010

In her work, New York-based artist Wangechi Mutu, who was born in Kenya, addresses issues related to black female identity, Western consumer culture, African politics, and postcolonial history. She became known for her collages that vacillate between beauty and horror. By using various materials such as glitter, tape, or animal fur in combination with magazine clippings, she creates idiosyncratic pieces that present the female body in a distorted, seductive, or commanding way and in a state of constant transformation.

For the exhibition “My Dirty Little Heaven,” Wangechi Mutu transformed the first floor into a suggestive environment, which recalls both a protective cocoon and the improvised buildings found in shanty towns on the peripheries of big cities such as Rio de Janeiro, Lagos, or Cape Town. Mutu seems to be less interested in reflecting on original cultural identity than in providing a vision of a future in which more and more people, as migrants and nomads, are becoming part of the “AlieNation.” In her view, cultural identity is no longer determined by geographical origins, ancestry or biological disposition, but is increasingly becoming a hybrid construct that people can determine and change themselves.